The De Morgan Foundation is custodian to an unparalleled collection of work by late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artistic duo Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919) and William De Morgan (1839–1917).

Evelyn's art has been identified as both proto-feminist and a spiritualist, and she utilised the female form within her oil paintings to engage with intellectual issues of her era, deploying allegoric metaphors that challenged the status quo.

She portrayed these mythological female protagonists as heroines in their own right, rendering them in a sympathetic light and producing a narrative that explored female personhood.

The De Morgan Foundation has partnered with Art UK to make these works available as prints to buy on the Art UK Shop.

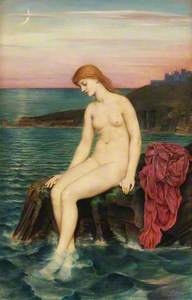

Ariadne

Ariadne in Naxos is one of Evelyn's earliest paintings and the first to be exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery, London.

Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos of Crete, is shown abandoned by Theseus on the island of Naxos after she has engineered his escape from the Labyrinth. A simple gold band denotes her royal status. Evelyn depicts Ariadne as a mournful and desolate figure as she awakens to discover her fate.

Ariadne's red chemise is of interest: the bold colour of passion morphs into the suffering of martyrdom as she is abandoned by Theseus.

The shells on the shoreline represent feminine sexuality, fertility, and love, and can be connected to Greco-Roman ideas of Aphrodite/Venus, who was born from the seafoam produced by Uranus' castration. As seashells are what remain of dead molluscs, the empty shells can be read as symbols of death, and the demise of Ariadne and Theseus' romantic saga.

Framed print of 'Ariadne in Naxos'

1877, oil on canvas by Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919)

Theseus, although not depicted, is the coward within this piece, for it was his promises that were untrue. It is Ariadne who is the tragic heroine.

Cassandra

The background of De Morgan's Cassandra depicts the fall of Troy. Cassandra, daughter of King Priam and Queen Hecuba of Troy, dominates the foreground of the artwork.

Roses bloom at Cassandra's feet, symbolising love (although it was unrequited and unwanted on her part). One cannot help but notice the laurel leaf diadem in Cassandra's hair, or the flame adornment on the hem of her mantle, and the snakes that wind up the decorative gold panel. Such imagery personifies Apollo, the Greek god of the sun.

According to myth, Apollo loved Cassandra and gifted her the ability to tell true prophecies. When she refused his love, Apollo turned the gift into a curse, and included the cruel caveat that none would believe her visions.

Blue is traditionally a representation of wisdom. The use of this colour for Cassandra's mantle can be read as a nod to her prophetic knowledge.

Framed print of 'Cassandra'

1898, oil on canvas by Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919)

Cassandra is bound in prophetic torment, as signified by the burning city and Trojan horse – both of which Cassandra foretold. This concept is further articulated by the laurel leaves, styled as jewellery, that rest across Cassandra's shoulders, evoking manacles and social constriction.

One must bear in mind that during the end of the nineteenth and in the early twentieth century, women campaigned for equal socio-economic and political rights, a crusade embodied by the women's suffrage movement.

Today we might label Evelyn herself as a feminist – she signed her support for the 1889 Declaration in Favour of Women's Suffrage. Within this artwork, Cassandra is immobilised by those who do not believe her words, and can be presumed to be an artistic representation of women's socio-economic and political rights in her own lifetime.

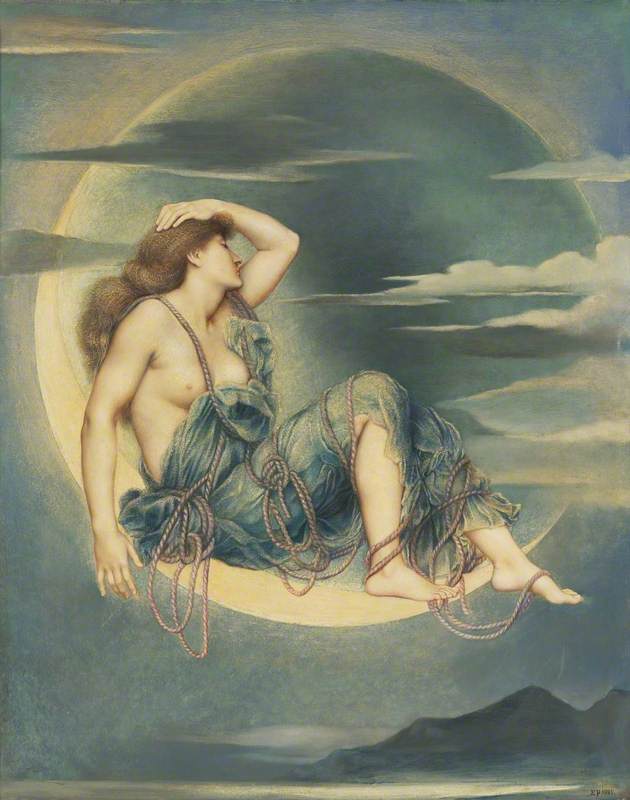

Helen

According to myth, Helen of Sparta (and later of Troy) was given as a gift to the Trojan prince Paris for awarding Aphrodite possession of the Apple of Discord, and thus the title of the most beautiful goddess. While this action secured Paris the patronage of Aphrodite, it earned him the enmity of Hera and Athena, and found their gifts of kingship and strategic wisdom eclipsed by Aphrodite's bribe.

The Judgement of Paris proved fatal, as it instigated the Trojan War, and Hera and Athena provided divine assistance to the Greeks during their 10-year siege of Troy, and the ultimate destruction of the House of Priam.

De Morgan's Helen of Troy is laden with symbolism. Similarly to Cassandra, roses riot across the base of the artwork, symbolising love. A waning moon is depicted, and on the distant coastline, Troy is visible. Sphinxes of black stone frame the sides of the painting, evoking an eastern setting.

The inclusion of Troy alludes to Helen's part in the city's destruction, but the pink of her mantle casts Helen as girlish and innocent, removed from the bloodshed. This soft colour can be compared to the darker, ruddy colour of Ariadne's mantle, and showcases how Evelyn utilised garment colours to illustrate the morality of her subject matter. Waves rendered in gold thread adorn the hem of Helen's mantle, linking her to Aphrodite, and their association with beauty, vanity and love.

Framed print of 'Helen of Troy'

1898, oil on canvas by Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919)

The mirror Helen holds emphasises her etherealism, and the inclusion of the decorative, Botticellian Aphrodite evokes Greco-Roman and Renaissance connotations.

While there is much debate as to whether Helen journeyed to Troy willingly or under duress, Evelyn depicts her as innocent of misconduct, and a young woman taken far from home rather than a woman who knowingly led Greek men to their deaths.

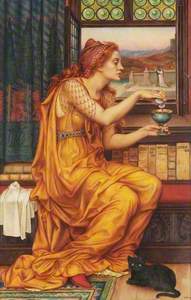

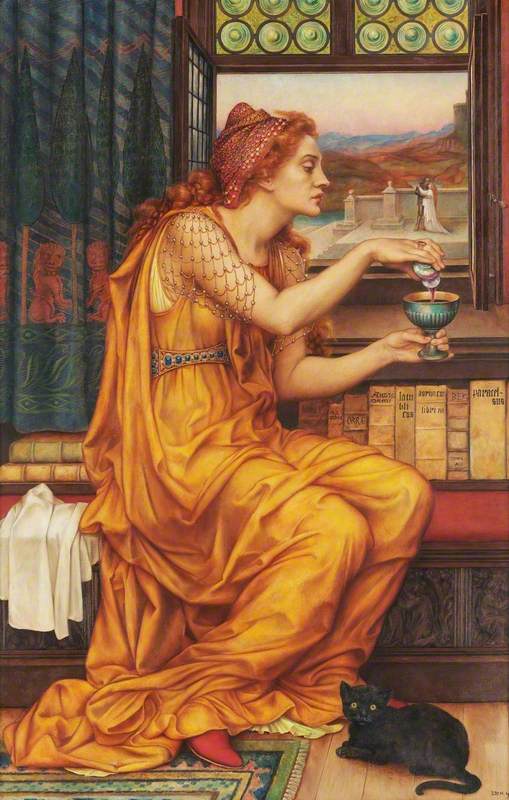

The Love Potion

Evelyn selected a medieval style for the tone of The Love Potion and used the central female figure to engage with diverse concepts.

Mrs Stirling (Evelyn's sister) misidentified the woman and her motives as: 'A witch in bright yellow, with a callous, cruel face, mixing a potion to upset the lovers who are seen on the terrace in the distance... by her side are books upon Black Magic.'

The accepted categorisation of this piece within Evelyn's body of work is Spiritualism. This movement centred on the belief that one's soul would reach enlightenment through a series of progressions. During this era, Spiritualism thrived due to religious criticism, philosophical rhetoric, and evolutionary theories.

Framed print of 'The Love Potion'

1903, oil on canvas by Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919)

While tomes are present in the painting, they are philosophical, spiritual, and scientific in nature, signifying the woman's intellectual evolution, and the overall tone of Spiritualism. A flippant, ironic nod to the belief that witches were assisted by animals explains the inclusion of the black cat.

Evelyn would have resonated with the Spiritualist belief system, explaining her inclusion of symbolic colours that were important for denoting where one was on the Spiritualist odyssey.

The alchemic symbolic colours are as follows: black denoted guilt, sin, and death; white represented purification; yellow conveyed one's approach to salvation; gold represented the zenith of spiritual enlightenment. This colour system is used within The Love Potion, with the yellow-gold of salvation worn by the woman herself, showcasing her spiritual realisation. Pearls, which decorate the net draping across her shoulders and hair, emphasise her femininity and wisdom.

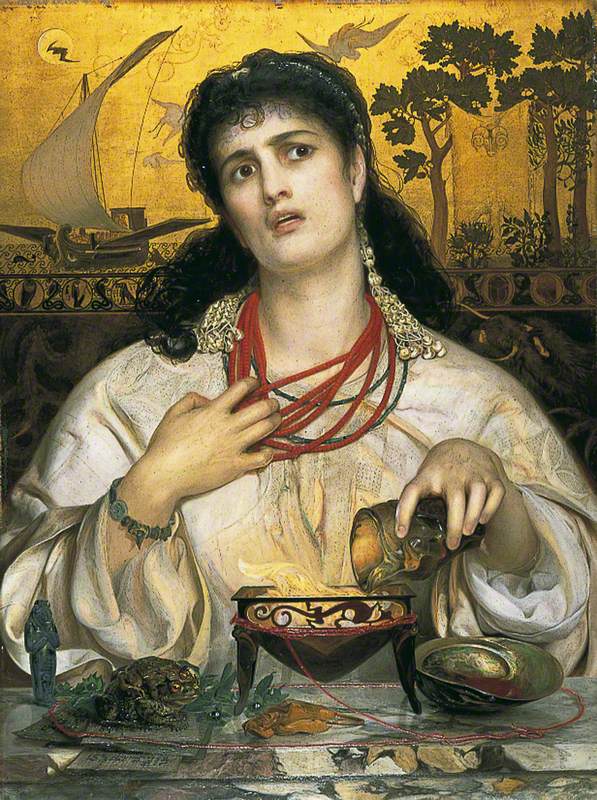

The Love Potion can be compared to De Morgan's Medea (in the Williamson Art Gallery) and read as an alternative avenue of feminine power and witchcraft.

Both women are wise individuals involved with the occult, as the pearls, potions (note the similar wine-red colours) and feline familiar accentuate, yet the subject of The Love Potion is an ethereal and enlightened sorceress, far more confident of her abilities.

This piece excellently examines how Evelyn used Spiritualism to subvert traditional female roles and stereotypes, presenting audiences with an enlightened, female-driven perspective that paired femininity with intellectualism, easily misidentified as wrathful sorcery.

These artworks by Evelyn De Morgan highlight her use of allegoric metaphors and symbols to challenge mainstream ideas of womanhood in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Evelyn De Morgan

unknown photographer

You can view more of her work in the collection held by the De Morgan Foundation, finding thematic strands that remain relevant to our own society and current events.

You can also own prints of these works and choose from many more at the De Morgan Collection's pages on the Art UK Shop.

Hannah Crichton, freelance writer

Further reading

T. Gantz, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, 1993

E. Lawton Smith, Evelyn Pickering De Morgan and the Allegorical Body, 2000

J. Marsh, 'Pre-Raphaelite Sisters', The Journal of William Morris Studies, Vol. 23 (4), 61–69, 2020

J. Oberhausen, 'Evelyn De Morgan and Spiritualism', Evelyn De Morgan: Oil Paintings, De Morgan Foundation, 1996

D. Ogden, Night's Black Agents: Witches, Wizards, and the Dead in the Ancient World, 2008

P. Yates, 'Evelyn De Morgan's Use of Literary Sources in Her Paintings', Evelyn De Morgan: Oil Paintings, De Morgan Foundation, 1996

.jpg)