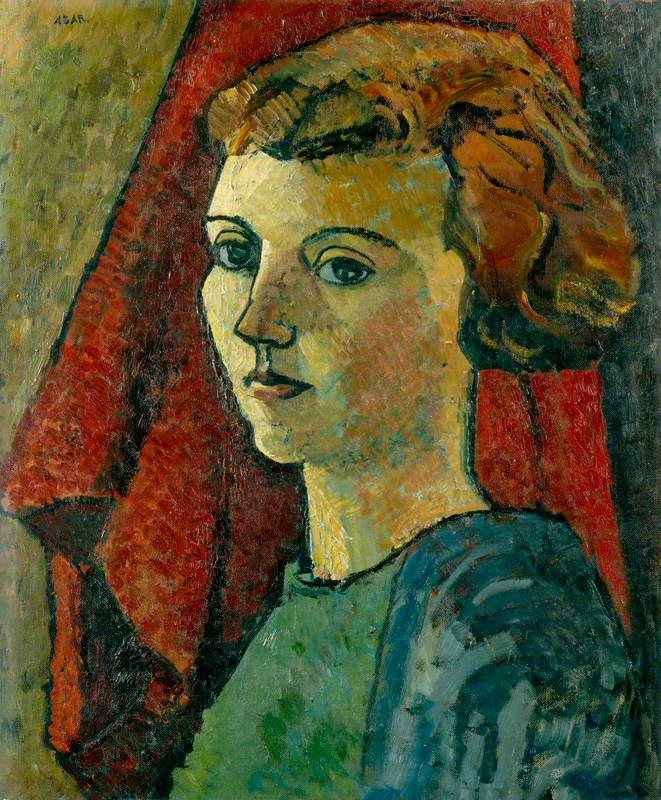

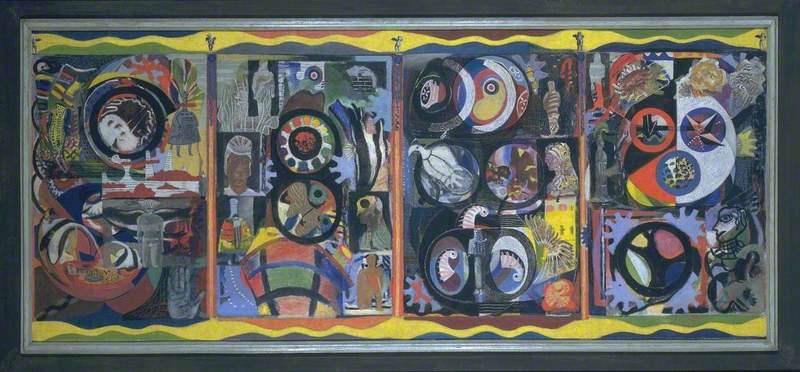

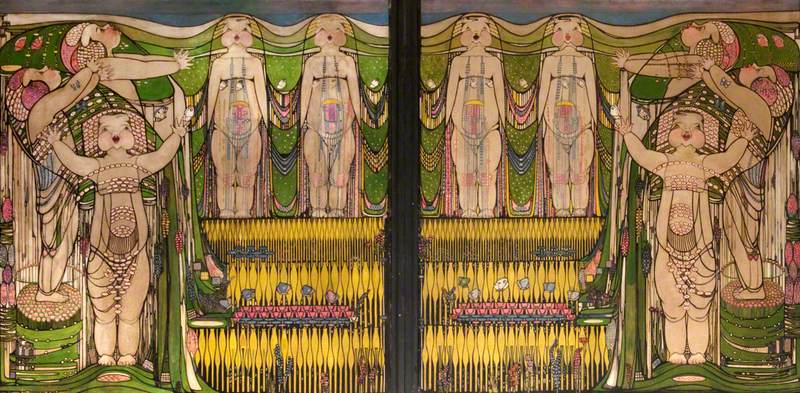

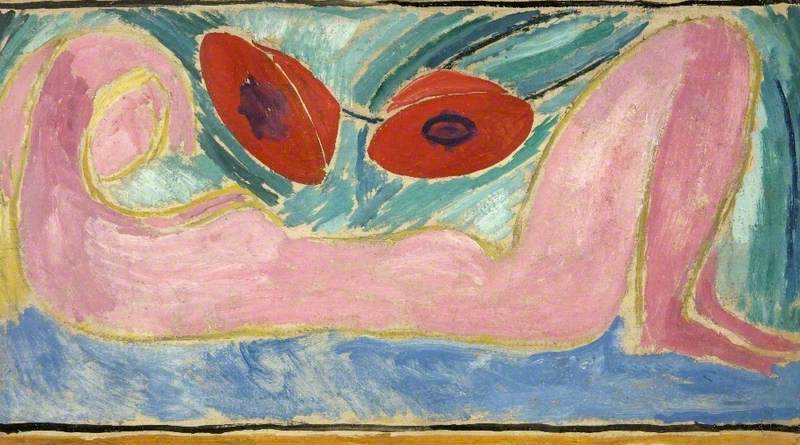

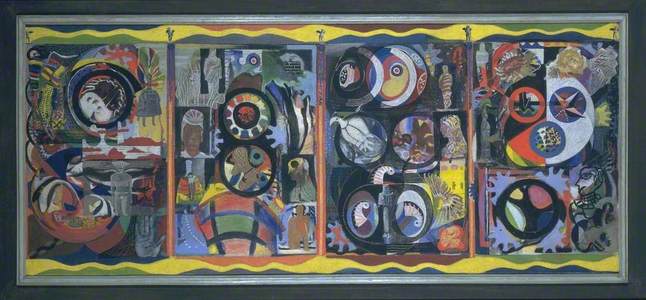

Eileen Agar (1899–1991) professed surprise in the spring of 1936 when she was officially identified as a Surrealist. ‘Am I?’ she replied when Roland Penrose and Herbert Read came to her studio and told her she was. These two movers-and-shakers of the English art world were rounding up like-minded artists to be included in the International Surrealist Exhibition scheduled for that summer in London. In some ways it was not a difficult task, as the English had a natural predisposition towards the surreal – just think of William Blake and Lewis Carroll. Agar had discovered Surrealism for herself in Paris when she lived and worked there in the late 1920s, but she was equally interested in Post-Cubist abstraction, and her own style oscillated between the two, deriving strength and formal ingenuity from both. Indeed she was experimenting widely in the early 1930s, delving into her psyche for the kind of subject and theme that would have intense personal relevance as well as a wider, more universal resonance. Amongst her supreme achievements of those years, The Autobiography of an Embryo (1933–1934), a large landscape format painting on board some seven feet wide, is a particularly startling and evocative statement.

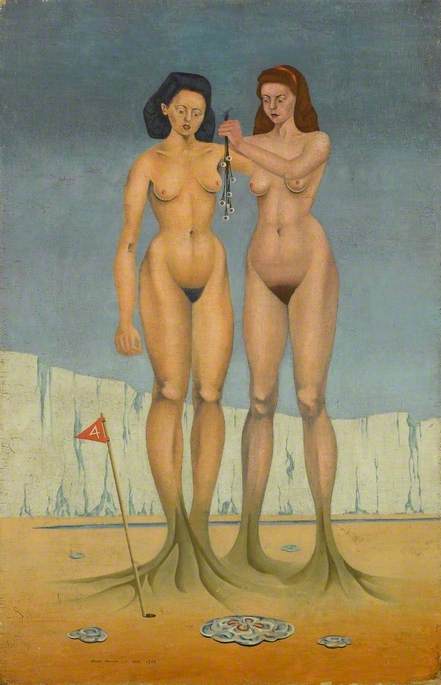

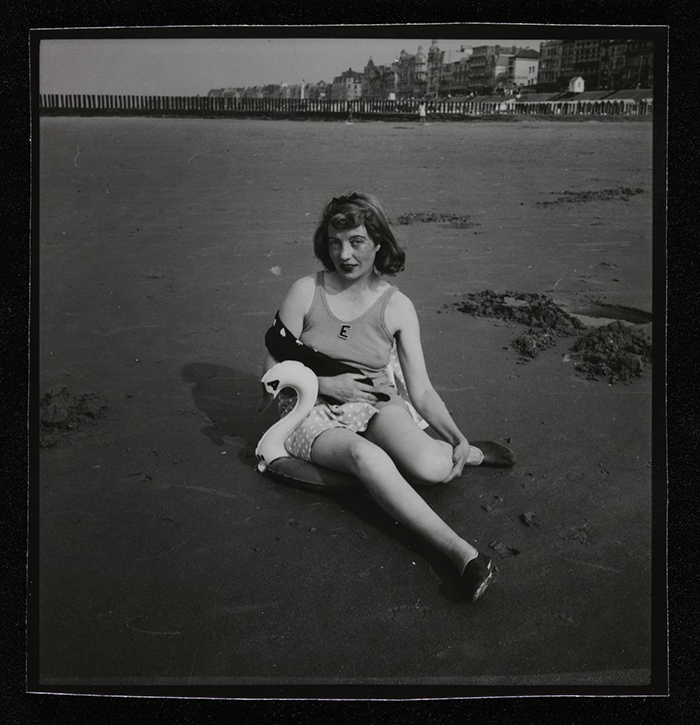

Photograph of Eileen Agar sitting on a beach with a plastic swan

1938, modern copy print by Joseph Bard (1882–1975)

I was first made aware of this extraordinary picture when Eileen Agar was faced with the problem of moving house. At the end of 1985 I had met Eileen, introduced through her literary agent who I’d met by chance at a party. Eileen had been trying unsuccessfully to write her memoirs, and all the publishers her agent had approached suggested she concentrate more on writing about her own life, rather than trying to construct a monument to her late husband, the Hungarian author Joseph Bard. Clearly she needed professional help, and I was hired to assist her. I did not become her ghost-writer, instead we collaborated. I would ask her to write specific scenes, or record her talking about key incidents or people, then take the new material home and rewrite it in her style, trying to piece it together as vibrantly and coherently as one of her celebrated collages. During this lengthy but enjoyable process we had become friends, and it was to a friend that Eileen confided her worry about what was in the attic.

It’s almost as if it were too personal and too revealing – too raw perhaps – for public consumption.

Her home then was in West House, Melbury Road, Kensington, one of those old Victorian houses in the Artists’ Quarter (Lord Leighton had lived

The painting I manhandled out of the attic was The Autobiography of an Embryo. It was clear to me at once that this was a major painting, and quite soon I became convinced it was a masterpiece. No sawing this in half or giving it to me (though of

That this was an intensely personal, if not actually private painting, is indicated by the fact that it doesn’t seem to have been exhibited much prior to my rediscovery of it in Eileen’s attic. As far as I’m aware it was only shown once in the 1930s – crucially it wasn’t in the 1936 International Surrealist show – when it hung in the Ninth Exhibition of the National Society of Painters and Sculptors at the Royal Institute Galleries in London in 1938. It didn’t attract a great deal of attention then and didn’t feature in either of the subsequent retrospectives of her work, in 1964 and 1971. It made its imposing reappearance in 1987 in Agar’s solo show at the Soho gallery of her London dealers Birch & Conran, and the Tate bought it from there.

Elsewhere Agar wrote of what she called ‘womb-magic, the dominance of female creativity and imagination’.

Why wasn’t it included in the prestigious 1936 exhibition? Was it too big? Unlikely – there were several sizeable paintings as can be seen from installation shots of the galleries. Intriguingly, Agar was represented by eight works in that show, but the

The Autobiography of an Embryo currently hangs in Tate Modern in the section devoted to International Surrealism where it continues to arouse passionate debate. But how autobiographical is it? In her notebooks of the

Andrew Lambirth