The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge has one of the most imposing and grandiloquent entrances of any museum in the world. Confronting the visitor in the main hallway is a double staircase leading to a spacious landing festooned with sculpture under a dome forming part of a spectacular display of polychrome decoration in several materials. Such a statement is perhaps only equaled elsewhere by the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Hermitage in St Petersburg or the National Gallery of Art in Washington. And, as in those museums, what lies beyond at the Fitzwilliam does not disappoint even if the galleries themselves are more understated.

Amongst the strong representation of Impressionist and Post Impressionist pictures is one that seems to me to have a specific resonance for our own world that is so dominated by the transient, the ephemeral and the fugitive.

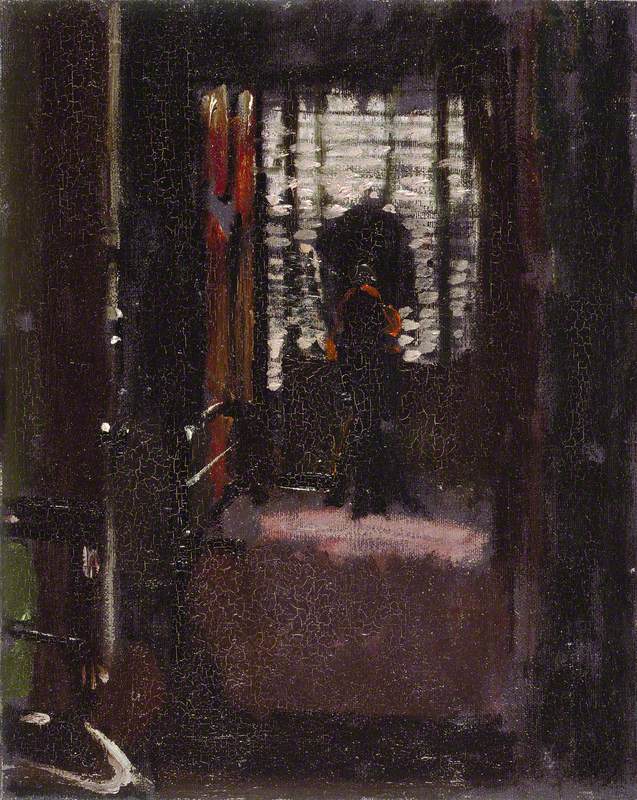

At the Café was painted by Edgar Degas in Paris c.1875–1877. During the 1870s the artist became fascinated by scenes from contemporary life and it is not difficult to imagine him sitting in a crowded, noisy café observing these two young women in eager conversation. Degas encourages the viewer to eavesdrop as if we are sitting at a neighbouring table. The loose, almost haphazard brushstrokes, together with the extensive areas of uncovered canvas, suggest that the painting is unfinished, but in fact Degas calculated the visual effects of his work very carefully, especially the use of colour, and there can be little doubt that this composition was as fully realised as he needed. He left nothing to chance, just as he chose his motifs with the greatest deliberation even if forced to seize the initial image instantly as if on the wing.

The figures in At the Café are anonymous and the exact nature of their relationship or their encounter is unknown. An element of concern is denoted in the poses as the figures huddle together in a conspiratorial manner – an aspect of the painting that underlies Degas's great skill as a draughtsman. The artist liked to explore cafés, theatres, racecourses and various workplaces where different social classes overlapped and social barriers were broken down. Such situations gave him psychological insights that illustrated the reality of the human condition in late-nineteenth-century France. Degas brought an almost surgical precision to his exposure of the frailties, insecurities and anxieties resulting from a society in a perpetual state of flux.

What most appealed to Degas, however, were the contradictions of modern life and his attitude is perhaps a reflection of the fact that he himself remained a paradox even to those who knew him well. His friends and fellow artists found him to be radical in art, but conservative in politics; sociable one day, but reclusive the next; encouraging and dismissive by turns; charming, well-mannered and witty when he chose, but increasingly acerbic and caustic with age. He was also a brilliant, although sometimes wounding, raconteur and mimic, and it is hardly surprising that his favoured mode of speech was the aphorism. It is these same characteristics that Degas translates into paint in such works as At the Café, which is a supreme example of his relentless examination of the Parisian world of his time. Such poignant paintings surprise us by the depth of the artist’s feelings, the extent of his insights and the range of his sympathy for the plight of human beings.

Christopher Lloyd, former Surveyor of The Queen’s Pictures