Since the industrial revolution of the nineteenth century, London has been one of the most polluted cities in the world. The bad weather, smoke and smog, historically referred to as 'London fog', was so characteristic of the city that countless artists and writers took inspiration from the atmospheric pollution. Charles Dickens once described London as a 'sooty spectre' and the Impressionist painter Claude Monet, capturing the Thames from his Savoy hotel room, observed that 'without the fog, London would not be a beautiful city.'

Breathe:2022

Today, without the constant burning of coal the density of London's pollution has somewhat improved. But the problem persists, as it does in all major cities across the globe. According to the London Air Quality Index, air pollution in London regularly surpasses the UK and World Health Organisation limits, meaning its residents are regularly exposed to harmful pollutants that can be life-threatening.

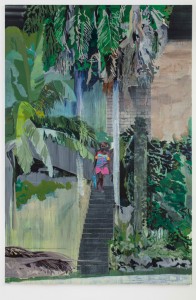

The artist Dryden Goodwin has been raising awareness about air pollution for many years. His most recent project in collaboration with Invisible Dust, Breathe:2022 is a public artwork comprising 1,000 drawings projected across the Borough of Lewisham. By capturing the likenesses of several local environmental activists, the project highlights the urgent issue and political apathy towards clean air. His delicate drawings – projected into public spaces and rendered into eye-catching animations – can be viewed in congested parts of the Borough; under bridges, walls and alongside major roads.

Breathe:2022, Catford Townhall

Importantly, Breathe:2022 pays tribute to Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, the 9-year-old girl who died in 2013 due to severe asthma that was brought about by constant exposure to pollutants. Ella grew up in Lewisham, not far from the South Circular and other major roads. Rosamund, her mother, has worked tirelessly ever since to raise awareness about London's noxious air.

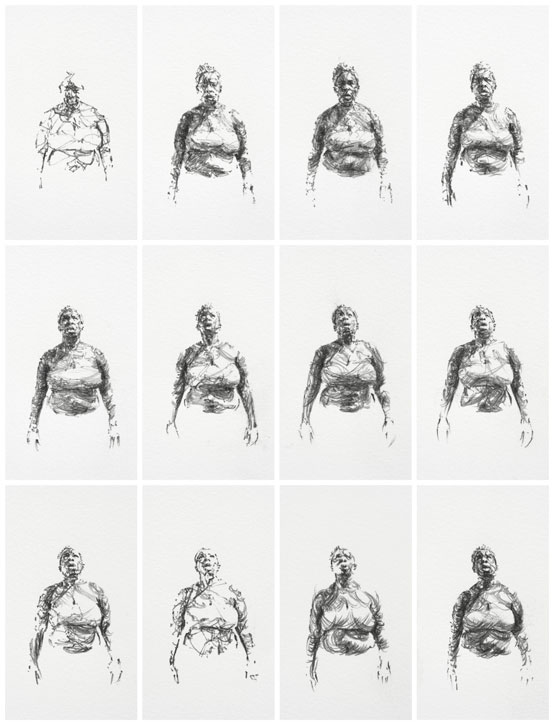

Alongside five other local activists, Rosamund was one of Goodwin's subjects. His drawings of her, delicate yet defiant, reflect her fighting spirit as well as the dynamic between artist and subject. 'We had an extended conversation when she came to my studio. During the visit I asked her to get out of breath so I could focus on her breathing while I filmed her. I wanted to capture the sense of someone fighting for breath.'

Rosamund Adoo-Kissi-Debrah

While concentrating on her laboured deep breathing, Rosamund reflected on Ella – 'this was what my daughter couldn't do'. The strength conveyed in Goodwin's drawings reflects her battle as a mother and environmental campaigner who has lost one of the people closest to her. Invited by Invisible Dust to work in partnership with Dr Ian Mudway, an Imperial College researcher in environmental toxicology, Goodwin says that research reveals that the greatest effects of air pollution are on the developing body – on young children.

It is also evident that air pollution disproportionally impacts communities of colour in the UK, many of whom come from poorer immigrant backgrounds and live in the less expensive, congested outskirts of cities. Anjali Raman-Middleton, the co-founder of Choked Up and one of Goodwin's other subjects points out that 'for people of colour in particular we are forced to choose between our communities and culture, and our health – this isn't a choice that anyone should have to make.'

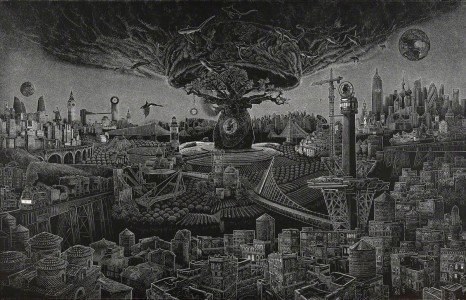

Breathe:2022

A Lewisham resident and a father of two children, Goodwin lives not far from where Ella grew up. Her death further heightened his fears for his own children, one of whom featured as the main subject in his first iteration of Breathe in 2012, for which he created over a thousand drawings of his then five-year-old son Heath Cole-Goodwin, inhaling and exhaling. The same son, now a teenager is also featured in Breathe:2022. 'Air pollution is something you're conscious of at a low level when you live in a city. But when you have a child, you become more concerned because of their vulnerability.'

Breathe 2012 was projected on the roof of St Thomas' Hospital, London – visible from the Houses of Parliament on the other side of the Thames. But not enough has been done to change environmental and air pollution policies since then. 'The most alarming thing about our current situation with air pollution is how little has happened politically.' Goodwin says. 'However, Ella's tragic death sparked mobilisation amongst younger campaigners in Lewisham who wanted to actively do something about the air that we breathe. Breathe:2022 tries to express this building energy and drive for change.'

Besides Rosamund and the Ella Roberta Family Foundation, the project included other activist organisations such as Choked Up, Mums for Lungs, Climate Action Lewisham and Forest Hill Society's Clean Air SE23 campaign, including individuals such as Ted Burke, Tafari McCalla and Alice Tate-Harte.

But why tackle this issue through the artistic medium of drawing, rather than something more direct like film or photography? As Goodwin tells me, 'there's something direct about putting a mark on a page, it's almost like a caress or holding someone. It's an empathetic gesture. When you're making each drawing you're trying to both convey and receive messages across illusory space. There's also a very visceral delicacy about graphite on paper, which mirrors the vulnerability of the body.'

Breathe:2022

Indeed, the artist's drawings are emotive and eye-catching. In an image-saturated world where we are constantly bombarded with photography and video, often for commercial purposes and advertising, the intimate nature of his drawings stand out and convey the psychological proximity between artist and sitter. 'This project is about drawing people in, and making them more aware of the act of breathing. As an artist, you're scanning the body physically, but also psychologically and emotionally. The drawings are small, but by projecting and animating them it creates a degree of heightened focus and an intensity of looking.'

As Goodwin and Invisible Dust highlight, the WHO estimates that urban air pollution is responsible now globally for about 8% of lung cancer deaths, 5% of cardio-pulmonary deaths and about 3% of all respiratory infection deaths, though it is still not prioritised as an urgent issue by the UK government. According to Goodwin, 'policymakers need to think beyond their own experiences, and into the future lives of others – my drawings become a metaphor for that need for empathy and collective action.'

Breathe:2022, Catford Townhall

To extend the community engagement in this urgent topic, Invisible Dust plans to present a free 'community day of air action' entitled 'We Breathe, Together' on 17th September 2022, in partnership with the Horniman Museum. In September there will also be the schools programme 'Drawing Breath', giving over 100 secondary pupils from Lewisham the chance to work with Goodwin to create a collaborative air pollution-focused animation.

When asked whether the public health crisis following COVID has made people take public health and clean air more seriously Goodwin responds positively: 'There's a greater sense of urgency around these issues in 2022. In comparison to the first iteration of Breathe in 2012, there is now a greater acknowledgement for the need for social justice and an understanding that people are affected differently.'

But there is certainly more to be done politically. 'There needs to be more radical changes in policy, rather than paying lip service. We also need to see a building of momentum locally with people empowered in their communities and becoming catalysts for change. This will incrementally contribute to addressing this critical global challenge.'

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

Breathe:2022 will remain in public locations around Lewisham until December 2022. The project will culminate as a large-scale projection animating over 1,000 drawings in November 2022 to close the programme.

Breathe:2022 is also featured at the Wellcome Collection, as part of their new exhibition 'In the Air', open to the public until October 2022. Sequences of posters will also be shown along Euston Road as part of the Bloomsbury festival in October 2022.