In The National Gallery in London, there's a small portrayal of a miracle which presents the same man twice. According to John 9:1–7, Christ applied a paste of spittle and dirt to a blind man's eyes, which gave him sight. In the painting we see the man receiving Christ's strange medicine and – having bathed his eyes in the water to the right – looking up to the heavens, letting go of his now redundant cane.

The Healing of the Man born Blind

1307/1308–1311

Duccio (c.1255–before 1319)

This unreal double appearance is an example of continuous narrative, which is defined by the scholar Lew Andrews as when 'a number of actions occurring at different moments but involving the same characters are presented together in a single unified space'.

We find several instances in Italian art, as early as the fourteenth century in works by the Sienese painters Duccio and Simone Martini, followed by examples from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries by Giovanni di Paolo, Sandro Botticelli, Jacopo del Sellaio and Pontormo. All the examples illustrated here are in The National Gallery, with the exception of Jacopo del Sellaio's The Story of Cupid and Psyche, which is in The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

A feature of European art from the late Middle Ages until the sixteenth century, continuous narrative is clearly irrational – people don't appear more than once in the same place. Yet it developed alongside the innovation of a natural view of three-dimensional space – the rediscovery of single-point perspective.

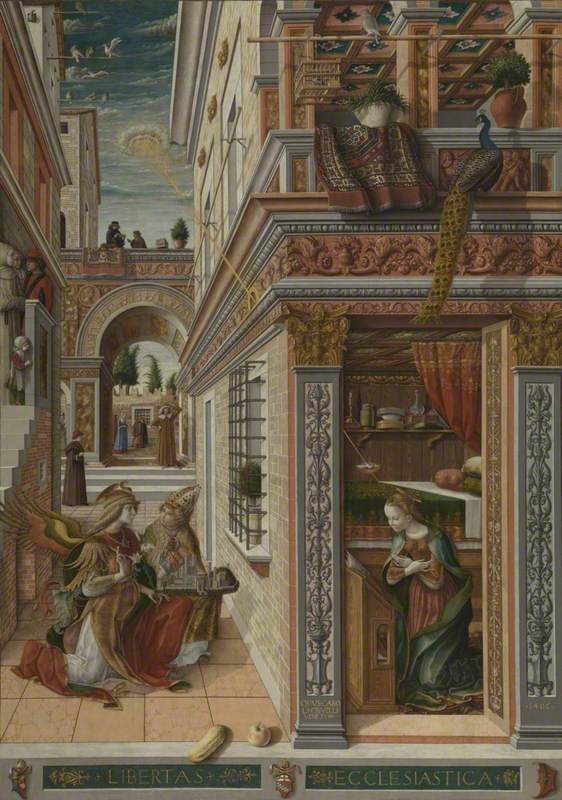

The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius

1486

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

These techniques appear to be in conflict – continuous narrative seems to militate against the efforts of perspective to create a sense of reality. However, Andrews claims that the two developments were in fact complementary, and that perspective gave space to accommodate the extra action and personnel characteristic of continuous narrative.

Continuous narrative takes three distinct forms: it can represent a physical transformation, such as a miracle. Secondly, it is used to suggest movement through space. Lastly, continuous narrative allows for the bringing together of different biographical episodes in a single scene.

An example of the first type – a physical transformation – Duccio's Healing of the Man born Blind (above), was made a century before the adoption of single-point perspective. Although the background architecture achieves a certain semblance of depth, the ground is largely left empty between the buildings and the figures in the foreground. As such, the crowd is crammed together in a flat, unreal mass. The recipient of Christ's miracle expresses his astonishment at the gift of sight, but has nowhere to go but to turn around, as if his flat form has been flipped over.

Saint John the Baptist retiring to the Desert: Predella Panel

1454

Giovanni di Paolo (1403–1482)

Painted in the mid-fifteenth century, Saint John the Baptist retiring to the Desert by Giovanni di Paolo shows the saint heading into the wilderness and demonstrates the second use of continuous narrative: implying movement through space. The artist has repeated his striding figure almost identically. Although we perceive a receding landscape with sharp peaks, John remains the same size, despite having covered some considerable distance. Consequently, he appears as a giant on the mountain path, and it seems that he hasn't travelled far because he appears no smaller. We can read the painting in two ways – the landscape may appear continuous (with John a giant in the mountains), or we can suspend that 'reality' and see John in two separate and discrete domains, painted on the same scale, as his undiminished form would suggest.

Four Scenes from the Early Life of Saint Zenobius

about 1500

Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510)

A further example, from the Florentine Sandro Botticelli, presents the third function of continuous narrative – telling a life story – this time in an urban setting that rigorously observes single-point perspective. In Four Scenes from the Early Life of Saint Zenobius, we see the saint four times, presenting from left to right his rejection of his fiancée, his baptism, the baptism of his mother, and his consecration as a bishop. His repeated appearance allows four biographical episodes to occupy a single setting, ingeniously using the architecture of the loggia – its steps and columns – as borders to frame the separate events.

Three Miracles of Saint Zenobius

about 1500

Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510)

Botticelli makes fuller use of the depth his perspective affords in Three Miracles of Saint Zenobius. Interestingly, unlike his Sienese forebears, Botticelli doesn't use continuous narrative to show the transformative nature of the miracles – it is Zenobius who is repeated, not the cured and the saved.

Jacopo del Sellaio's The Story of Cupid and Psyche has no fewer than twelve appearances by Psyche (including one as a baby on the far left) and four by Cupid. Despite the ample space available to her, the glamorous figure in a white dress is in danger of bumping into herself, so often does she populate the scene. The panel was made to decorate a marriage chest, and fittingly the narrative depicts Psyche's journey to her betrothal to the god Cupid.

Pontormo's Joseph with Jacob in Egypt glories in the depth of its space to an extravagant degree. In fact, it's hard to work out the lie of the land and the odd adjacency of the sloping hillside and the curving flight of stairs. This picture is a compendium of effects, including the sophisticated rendering of shade and shadow.

Joseph with Jacob in Egypt

probably 1518

Jacopo Carucci Pontormo (1494–1556)

Among all these distractions we may struggle to identify the replicated figures of Joseph and his father Jacob. Joseph's orange hat gives him away in three of his four appearances: at bottom right hearing a petition, halfway up the stairs with one of his sons, and top right, with his sons in Jacob's bedchamber. Having taken off his hat and holding it to his chest, he's there in the left foreground, presenting the kneeling Jacob to the Pharoah. Old Jacob is also in the very centre of the picture, leaning against a boulder.

This painting is perhaps the acme of the marriage of continuous narrative and perspective: so plentiful is the space that Pontormo has room to replicate two individuals to produce a total of seven separate figures. We might be tempted to add some duplicate children, until we realise that the two boys in green on the stairs and in Jacob's bedchamber – Joseph's sons – owe their similarity to biology rather than Pontormo's artistry!

Continuous narrative became scarce in the sixteenth century, and Joseph with Jacob in Egypt appears to be one of the last examples of its use. Now that painting was concerned to present naturalistic images, continuous narrative fell out of fashion.

Perseus turning Phineas and his Followers to Stone

early 1680s

Luca Giordano (1634–1705)

To solve the problem of representing physical transformation in a later age, Luca Giordano employed a different technique. In his Perseus turning Phineas and his Followers to Stone, the three figures on the left, Phineas and two of his men, are changing form before our very eyes.

According to the myth, Perseus, aware that he was outnumbered, grabbed the head of Gorgon and brandished it in the sight of his enemies. They turned to stone, frozen in the poses of their attack. We can see Phineas's head and torso already stiff and grey as stone, while his lower leg, at least for a few more moments, retains the pink tone of life.

The spark of imagination that led Duccio and other Sienese masters to paint duplicate figures occurred a hundred years before the innovation of single-point perspective.

When the artists of the fifteenth century found they had created a spacious stage for action in the net of their perspectival lines, some used the space to repeat figures – as we have seen – while a greater number persisted with the plain idea of presenting everyone once and once only.

Yet as a means of telling a story, continuous narrative retains its power to persuade and delight, as audacious in its own way as the experiments of Modernism to come.

Adam Wattam, writer

Further reading

Lew Andrews, Story and Space in Renaissance Art: The Rebirth of Continuous Narrative, Cambridge University Press, 1995

Timothy Hyman, Sienese Painting: The Art of a City-Republic, Thames and Hudson Ltd, 2003

John White, The Birth and Rebirth of Pictorial Space, Belknap Press, 1987