As soon as it became normal for women to go to art school in the late nineteenth century, they declared their new creative freedom in their clothes. From the start, they dressed colourfully, even flamboyantly in loose and easy clothes even when fashions were tight and drab (the tradition carried on too until the seventies).

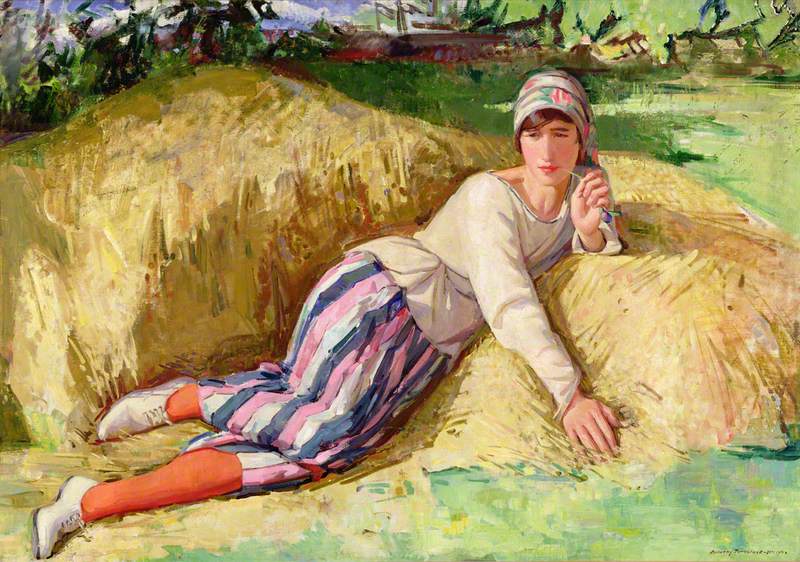

We see this artistic style of dress in Dorothy Johnstone's painting of her friend Cecile Walton (1891–1965), another Scottish artist active during the first half of the twentieth century. Painted in 1918, it shows her reclining on a haystack, pensively chewing the stem of a cornflower. She's wearing silk pantaloons striped in pink, blue and white, scarlet stockings and white brogues. Her smock top in natural-coloured cotton or linen sets off this flamboyance. The ensemble is rounded off with a brightly coloured headscarf.

An equally vivid picture of another friend and fellow artist, Anne Finlay (1898–1963), presents the sitter indoors, but is as colourful. She wears a kingfisher blue dress under a white overdress sprigged with pink flowers and sits on a luxurious coat with a scarlet lining. Her blue stockings set off her black shoes adorned with scarlet pompoms.

These pictures would both be stunning for the clothes alone and what they say about the confidence and self-esteem of both sitters and artist, but they are also typical of the brilliance of Dorothy Johnstone's (1892–1980) work around this time. Graduating in 1912, she was the star student at Edinburgh College of Art, not long after the new College was created out of the old Trustees Academy.

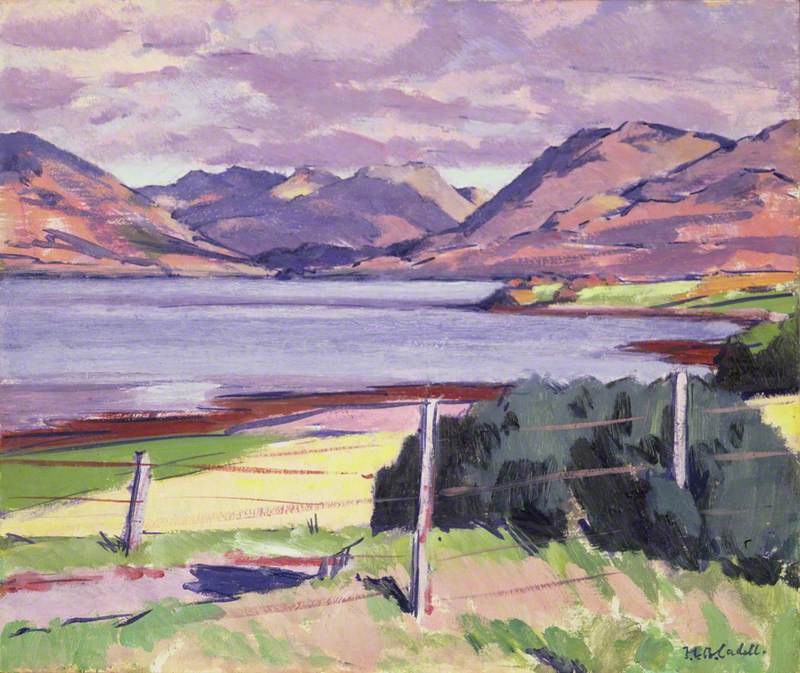

Johnstone was clearly aware of contemporary developments in Paris, and certainly, the College wasn't cut off from artistic European trends. Her older contemporaries in Edinburgh included the Scottish Colourists, S. J. Peploe and F. C. B. Cadell. Although their example might have influenced her work, in reality, it was a woman artist who seemed to liberate both her style and palette.

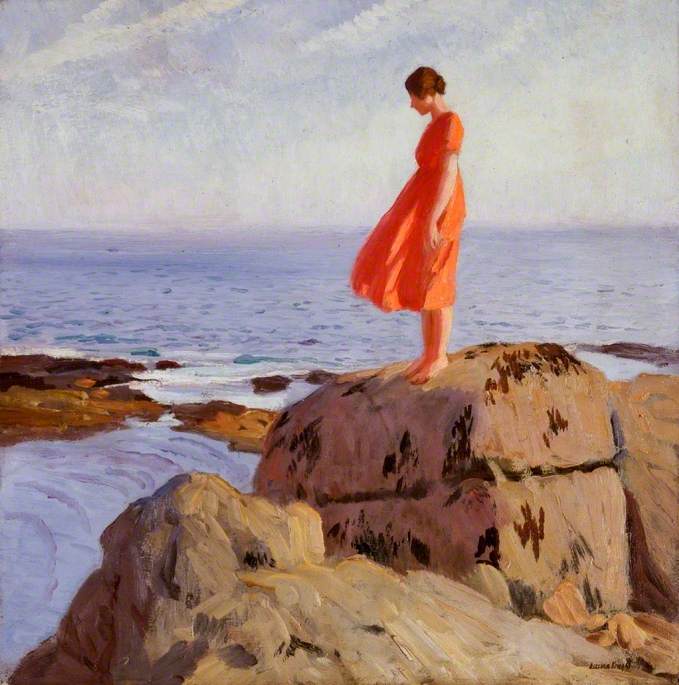

Laura Knight exhibited eleven pictures at the Royal Scottish Academy in 1916. Significantly too she had already shown a picture there in 1911, when Johnstone was still a student. It was called On the Rocks, a title that could fit several of Knight's marvellous paintings from that time of girls, rocks and the sea on the Cornish coast.

The artist's seaside paintings were particularly vivid. For instance, A Dark Pool, housed in the Laing Art Gallery, depicts a girl in a bright orange dress standing beneath a vast blue sky and sea.

When it came to colour, Knight acknowledged the impact of the Scottish artist Charles Mackie (1862–1920). Through his friendship with Paul Sérusier, the artist had close links to the French painters working alongside Gauguin at the turn of the century.

In 1891, Mackie was a founder member and in 1900 President of the Society of Scottish Artists, the group of young artists who, like the Vienna Secession a few years later, broke with the Academy to form their own exhibiting society. Women could be full professional members from the start.

It was perhaps because of Mackie that Knight chose to exhibit in Edinburgh and she may well have exhibited with the SSA before later submitting to the Academy. Certainly, her work shown in the city seems to have made an impression on Johnstone.

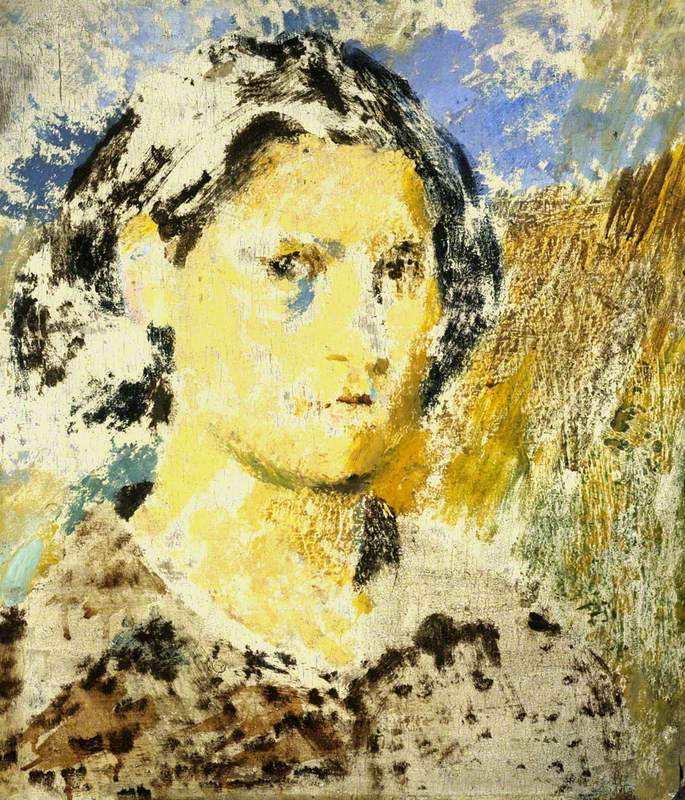

Rest Time in the Life Class

1923

Dorothy Johnstone (1892–1980)

Another older woman artist who also played a role in her life, however, was the illustrator Jessie M. King (1875–1949). In 1915, she and her husband Ernest Archibald Taylor – after a few years of teaching together in Paris – settled in Kirkcudbright, an artists' town in the southwest of Scotland.

In a radical gesture, King kept her own name after marriage. Dorothy Johnstone and Cecile Walton followed suit. After their marriages, Johnstone to the painter David Macbeth Sutherland, and Walton to Eric Harald Macbeth Robertson (also a painter), both women kept their own names. Knight, by contrast, took her husband Harold's name.

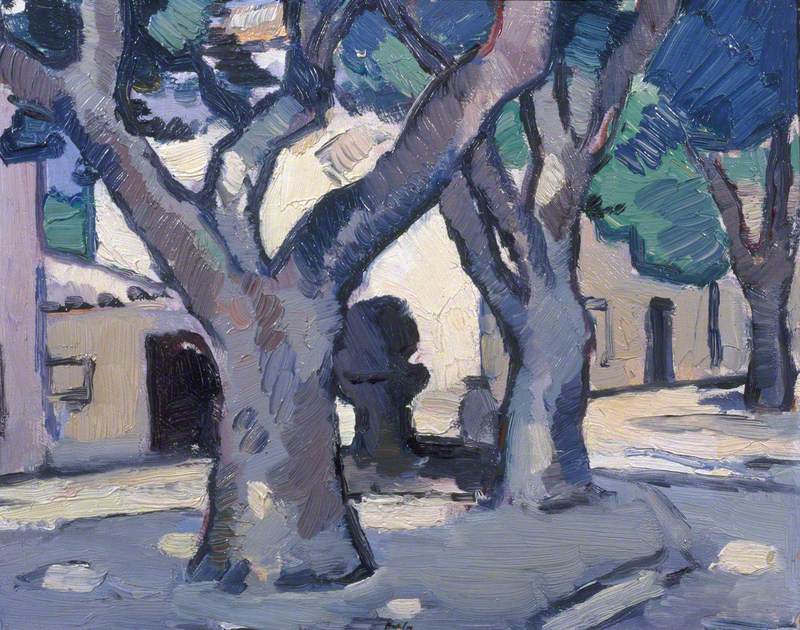

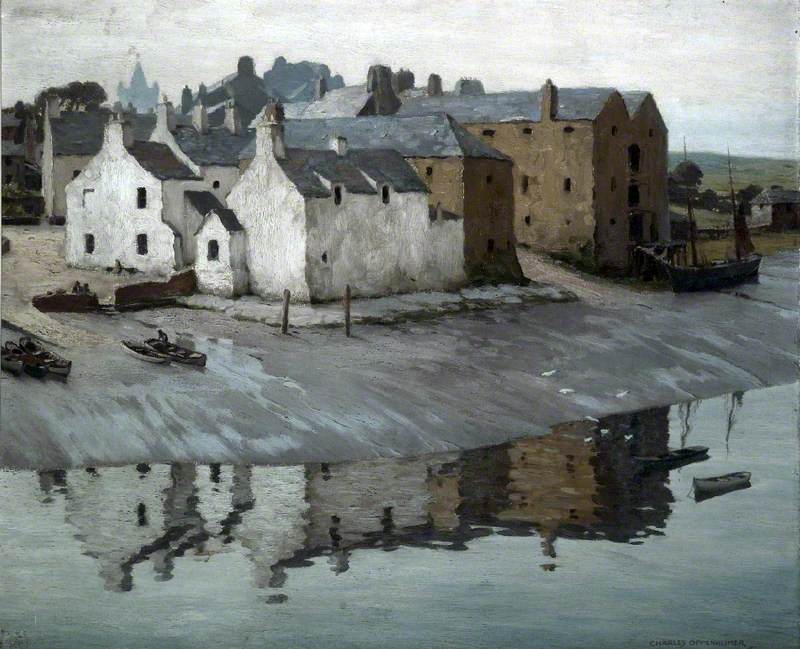

In Kirkcudbright, King and her husband rented out studio cottages to promising young artists. Johnstone rented one in Greengate Close on several occasions. There is a lovely picture of it by her in Aberdeen Art Gallery. Greengate Close was so-called from the emerald green gate King had designed for it. This vivid green is also visible on the drain pipes and window surrounds in Johnstone's painting

Greengate Close, Kirkcudbright, Dumfries and Galloway

1940–1980

Dorothy Johnstone (1892–1980)

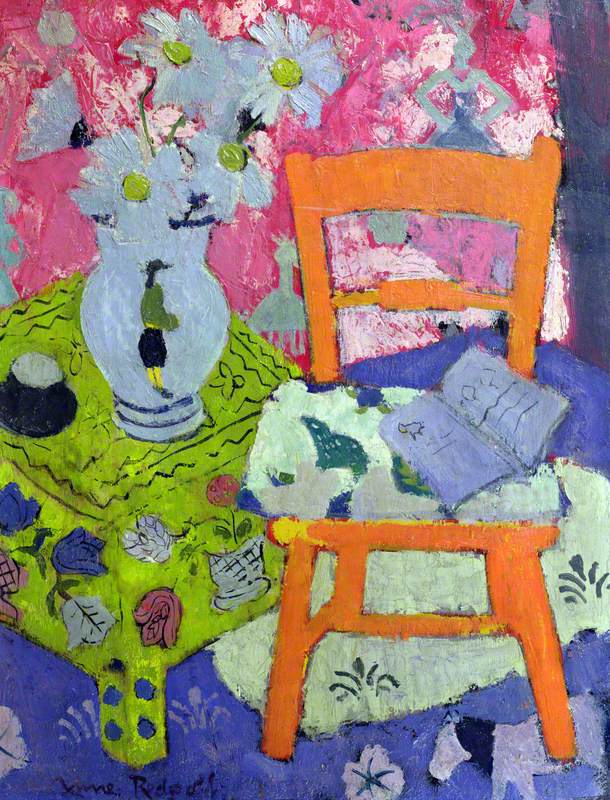

In 1916, Johnstone painted a glorious picture there called September Sunlight. The painting was given by Glasgow University to Edinburgh University in 1984 as a quatercentenary present. It shows a young girl at a sunlit window. She's sitting on a blue cloth and wearing an orange smock – such complementary colours are also typical of Knight. The window sill is painted brilliant blue and its reflection fills the white-washed interior with cool blue light.

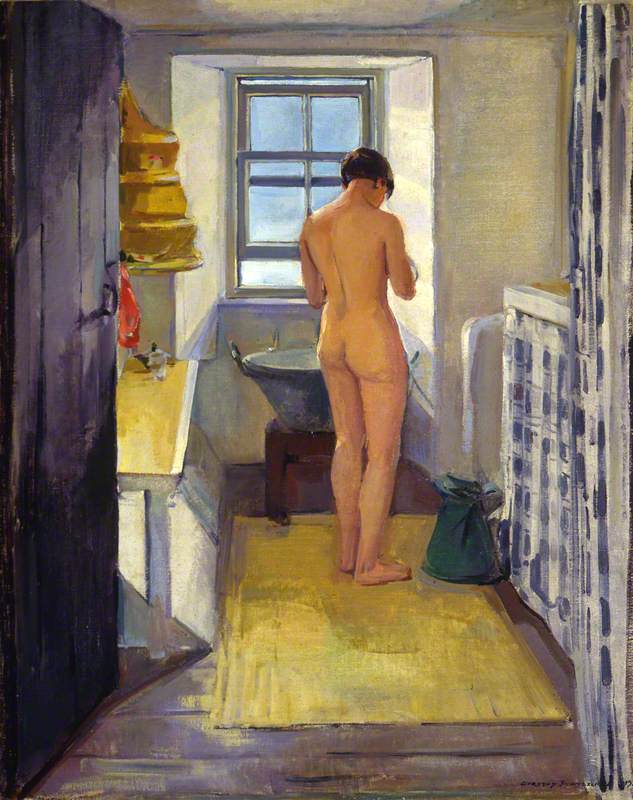

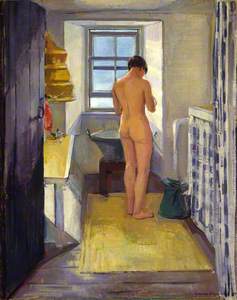

Johnstone's painting Black and Yellow shows a similar window. A naked girl is washing herself, standing on a yellow rug, the yellow of the title. The door and the floor seem to be painted black. This, in turn, gives the black of the title although blue light from the window is softening it to dark purple. Peploe and Cadell both favoured black floors, too, and we get a hint here of Jessie King's very modern taste in interior decoration.

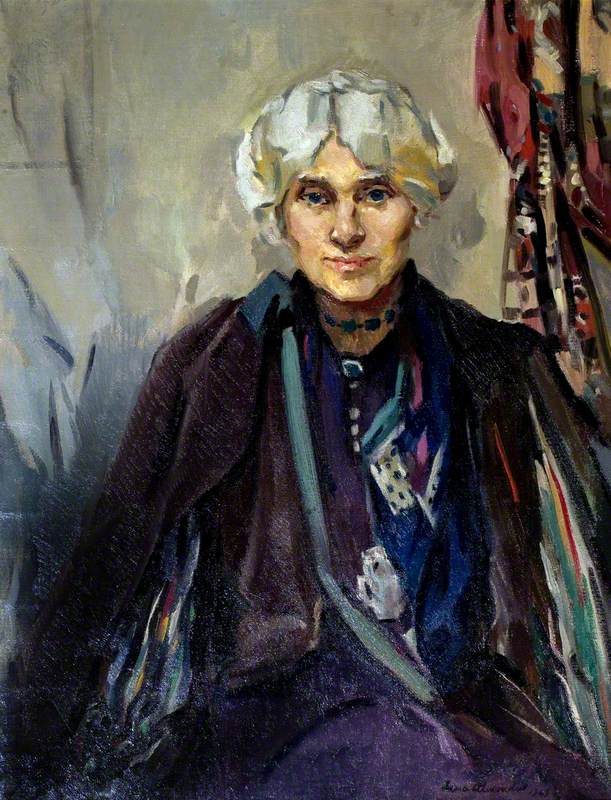

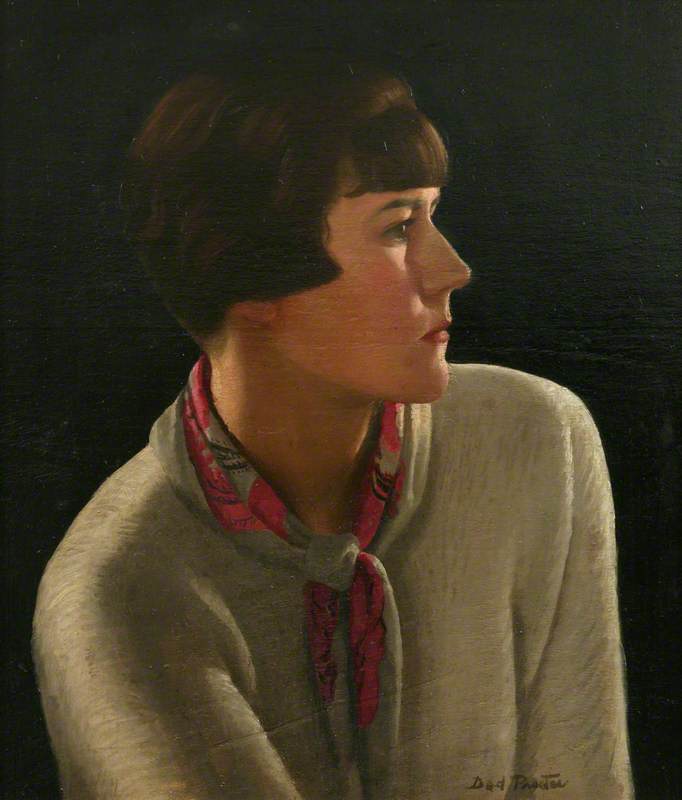

Jessie King also liked to dress flamboyantly. A portrait of her by Lena Alexander (1899–1983) painted in 1949 shows her even in the last year of her life wearing a beautiful purple cape with a rainbow lining.

In 1918 Johnstone again spent the summer in Kirkcudbright and in September Cecile Walton went down to stay with her. This was when she was painted in her wonderful striped pantaloons, reclining on a haystack. It celebrated her individuality and independence as a woman.

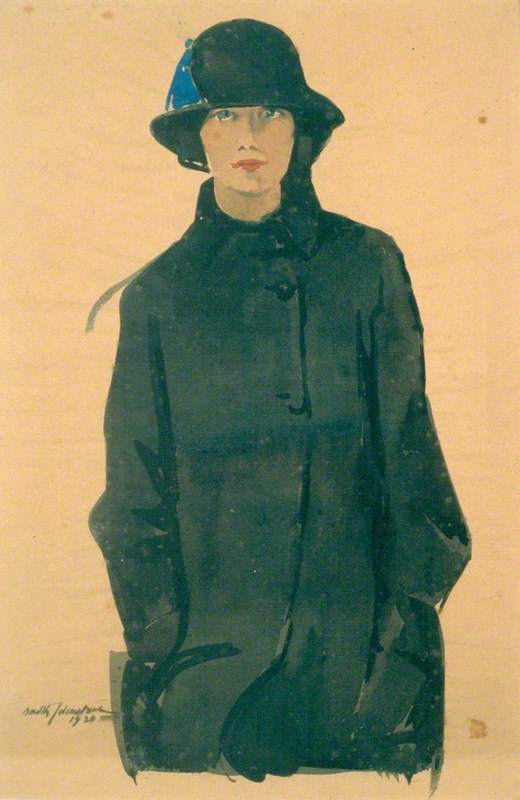

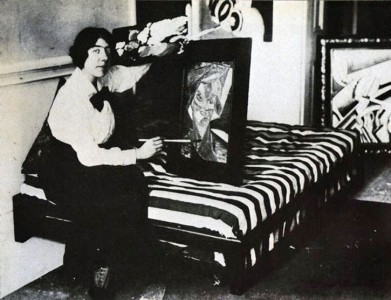

It has been suggested that Johnstone may have had an affair with Vera 'Jack' Holme, a British actress and suffragette. Between 1918 and 1919, Holme spent time with Johnstone and other artists in Kirkcudbright. In this photo of them together, Holme is seated on the left with radically short hair.

Vera 'Jack' Holme (left) and Dorothy Johnstone (standing)

1918, photograph by unknown photographer

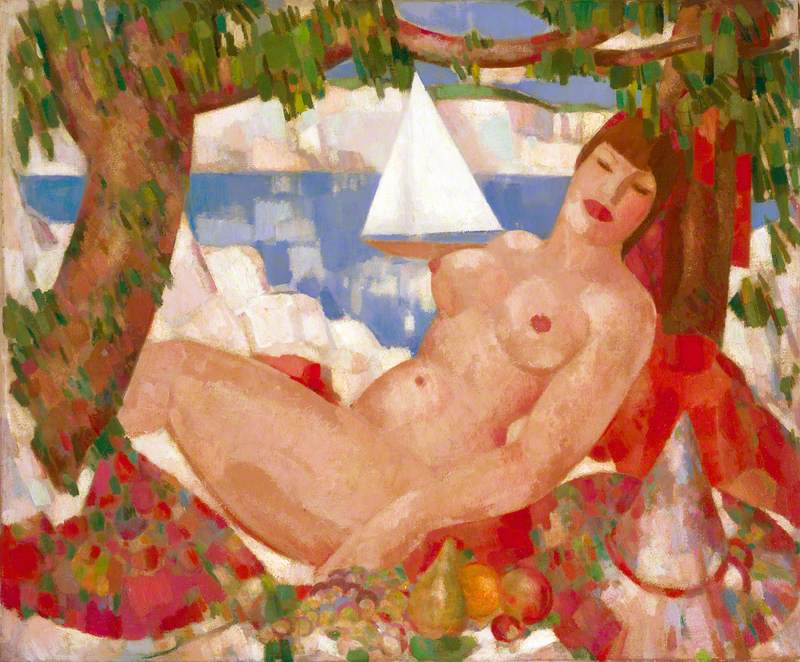

Cecile Walton's self-portrait, Romance, was completed in 1920 (after the birth of her second child Edward). It powerfully endorses the female individuality shown two years before in Johnstone's painting of her in a haystack.

Romance shows the artist sitting up in bed, naked to the waist with her new baby in her arms. Gavril, her older son, looks on while a nurse attends her. The composition echoes Manet's Olympia, a painting about women seen by men, but she turns it on its head so that it becomes a declaration of the dignity of motherhood.

Romance – Cecile Walton (1891–1956), with her Children Edward and Gavril

1920

Cecile Walton (1891–1956)

The present author complained in the press that it was a disgrace that the National Gallery of Scotland hadn't bought this icon of women's art when offered to them. An anonymous donor read the article, bought the painting and presented it to the Gallery, all within days. The 1922 painting Early Morning also shows Edward, now aged two, brushing his sleeping mother's hair.

Rest Time in the Life Class

(study)

Dorothy Johnstone (1892–1980)

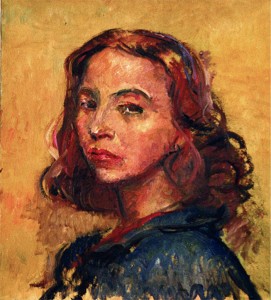

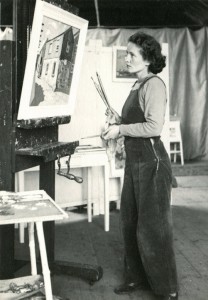

Dorothy Johnstone herself was such a star that it was natural that she should go from being a student at Edinburgh College of Art to teaching there. Several paintings provide a record of her time at the college, including Rest Time in the Life Class.

However by a cruel and profoundly sexist rule enforced by the Department of Education, when she married David Sutherland she was compelled to give up teaching. Sutherland was appointed Principal of Gray's School of Art in Aberdeen and so they moved there. There is no doubt that losing her post at the College, and perhaps also losing touch with her lively Edinburgh circle of artist friends, set her back as an artist.

In Aberdeen, she painted wonderful pictures of her family and went on exhibiting till shortly before her death in 1980, but the great majority of her work in public collections is from her brilliant early years.

After her death, several of these lovely paintings were found rolled up and neglected in her house in Aberdeen. Their survival restored to us the wonderful talent of a truly gifted artist.

Duncan Macmillan, art critic and art historian