Ganymede was 'the fairest of mortal men; wherefore the gods caught him up on high to be cupbearer to Zeus by reason of his beauty, that he might dwell with the immortals.'

So says Homer in the Iliad. Throughout antiquity, there was a fascination with the tale of how Zeus, king of the gods, fell in love with a human boy. The scene of Zeus swooping down from Olympus to steal away Ganymede, known as 'The Rape of Ganymede', appeared on pottery, frescoes, statues and mosaics.

Zeus and Ganymede

c.475–425 BC, Attic red-figured kylix, attributed to the Penthesilea Painter. Ferrara Archaeological Museum

While many ancient depictions from Greece show two humans in the tale of Ganymede, the Romans favoured a version more in keeping with Zeus' fondness for wooing mortals in zoological form. According to the Roman poet Ovid:

'The king of the gods was once fired with love for Phrygian Ganymede, and when that happened Jupiter found another shape preferable to his own. Wishing to turn himself into a bird, he nonetheless scorned to change into any save that which can carry his thunderbolts. Then without delay, beating the air on borrowed pinions, he snatched away the shepherd of Ilium, who even now mixes the winecups, and supplies Jove with nectar, to the annoyance of Juno.'

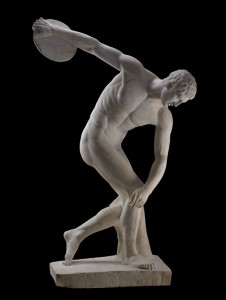

Roman statues tended to show Ganymede as a handsome youth accompanied by an eagle. Some of the best-known images of Ganymede and Zeus from ancient Rome showed the boy in the grasp of a vast eagle being swept up to the heavens. The rediscovery of ancient art in fifteenth-century Italy inspired paintings by some of the most famous artists of the Renaissance.

The vast number of works inspired by the tale of Ganymede speaks not only to the dramatic nature of the story or the beauty of the boy but to a deeper meaning of the narrative. Two divergent interpretations of the Rape of Ganymede were explored.

The first interpretation of the Ganymede tale is born from the homosexual relations that were acknowledged in some ancient Greek states. In Athens of the fifth century BC, a practice called pederasty was common in upper-class society. An older man, known as the Erastes, would seduce a boy, called the Eramenos.

To the ancient Greeks, it was natural that older men should lust for younger male lovers. These relationships were both sexual and social. It was expected that the older lover would introduce their beloved into society and help them find a position. This was done with the full knowledge and approval of the boy's father.

These relationships were not what we would today call homosexual. The older lover would typically have a wife at home and the younger lover would be expected to marry a woman later in life. The pederastic partnership was also heavily hedged about with social rules. Many Greek poets lamented the first growth of a boy's beard because that was the age at which their relationship had to end. Any man who carried on sexual relationships with other adults could expect to find themselves deeply ridiculed. The plays of Aristophanes contain lacerating lampoons of 'men-lovers'.

The second reading of the narrative saw Zeus' abduction of Ganymede as a deeply spiritual one. Even in antiquity, there were those that saw Ganymede's flight into the sky as a metaphor for the soul's journey into heaven. This interpretation would give later Christian artists an excuse to paint Ganymede, and his rounded buttocks, with such tender brushstrokes.

Even as they emphasised the Christian message of this scene, homosexual artists of the Renaissance were not blind to the more obvious meaning of the Ganymede myth.

Ganymede

c.1540?, black chalk by Giulio Clovio (1498–1578)

In 1532 Michelangelo gifted a drawing of Ganymede being carried off by Zeus to Tommaso dei Cavalieri. Tommaso was the object of the artist's affections and the recipient of many flattering poems. Perhaps the gift of a Ganymede drawing was appropriate as Michelangelo was 57 when he met the 17-year-old Tommaso.

The dramatic action of a boy being abducted by an eagle made the Rape of Ganymede a favourite subject for many artists and collectors. Some patrons may have requested a version of the Ganymede myth as an expression of their homosexual desires. Yet Ganymede would remain a dangerous icon at which to worship.

The Rape of Ganymede

about 1575

Damiano Mazza (active 1573) (attributed to)

Some transgressive artists would continue to make explicit references to Ganymede and Zeus' sexuality. Christopher Marlowe's tragedy Dido, Queen of Carthage (1594), sees Ganymede on stage begging for jewels from his lover Zeus. The god promises them to the boy 'If thou wilt be my love.' This is hardly surprising from Marlowe – he knew the classics well and is said to have declared 'All they that love not tobacco and boys are fools.' Yet even Marlowe here presents Ganymede as a mercenary lover.

In poetry, plays, and even common parlance, Ganymede came to stand for both paedophilic and homosexual tastes. Male prostitutes were commonly referred to as 'Ganymedes' in the eighteenth century.

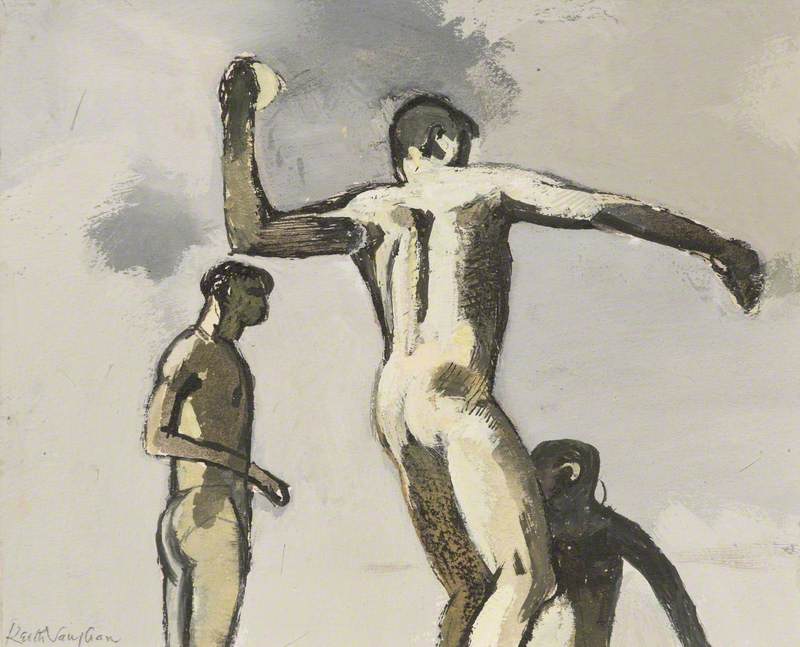

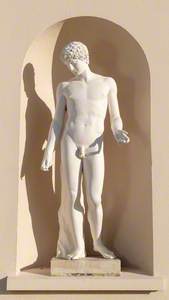

Ganymede in paintings throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries began to shift in appearance. Instead of the pre-pubescent boy displayed in antiquity, Ganymede was transformed into a youthful but manly figure.

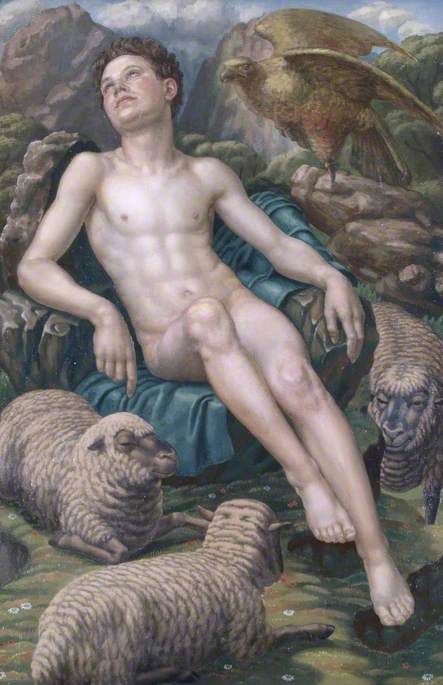

Homosexuality in the modern sense was only named and acknowledged in the late nineteenth century. While many homosexual men had to remain cagey about their love, there were some outspoken artists who were relatively open about their desires. For example, Ralph Chubb's poetry and writings were so explicit that they were once kept private in the British Museum. Today his works, including a painting of Ganymede before he is carried off, are some of the few made by a homosexual artist that explore the psychology of gay men.

Despite the ubiquity of Ganymede in western art, his popularity fell away in the late nineteenth century in favour of another symbol for homosexual love. It may be that openly displaying a work of Ganymede, with all of its illicit homosexual undertones, would too openly 'out' a collector as a Ganymede himself. Instead, a new icon was needed.

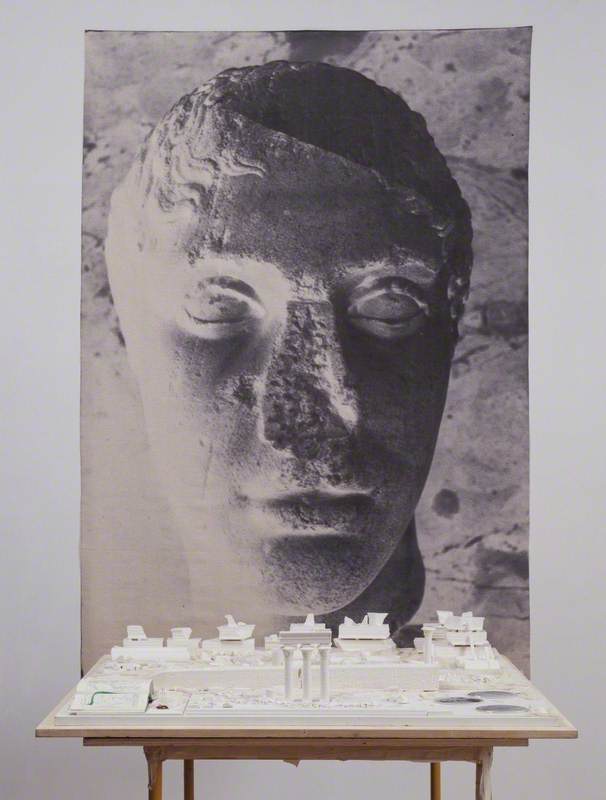

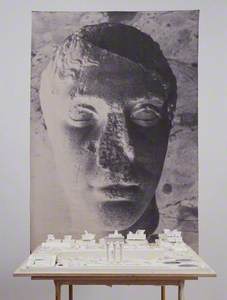

Antinous has one of the most famous faces to survive from antiquity. Dozens of images of Antinous have turned up in sculptures, carved in gemstones, and other archaeological contexts. Yet Antinous was not a famous conqueror, emperor or politician. Antinous was the lover of the Roman emperor Hadrian.

Hadrian was a well-known Philhellene – a lover of classical Greek culture. Even the fact that he sported a beard set him apart from previous clean-shaven emperors as a man who followed the Greek tradition. Hadrian would also find a lover in that same Greek tradition.

Hadrian met the young Antinous while touring the eastern provinces and took him as a lover. Antinous soon became an acknowledged favourite with Hadrian and joined the emperor on his restless journeys across the empire. Antinous even appeared in public art beside Hadrian, as here in a scene of a lion hunt. (The object's title reflects the belief by Sir John Soane that the roundel was of the emperor Trajan, but today the subject has been identified as Hadrian.)

In AD 130, however, tragedy struck. Antinous drowned in the River Nile aged just 19. Mystery surrounds the death. Was it an accident? Was it murder by jealous rivals? Or was it part of a religious sacrifice for the health of the emperor? All were suggested but it is likely we will never know the truth.

What we do know is that Hadrian was grief-stricken. He founded a city at the site of his lover's death and called it Antinoöpolis. Hadrian also created a cult to worship Antinous.

The Roman pantheon was relatively expansive and always able to absorb new deities. Apotheosis, or the glorification of a subject to divine levels, was common for Roman emperors after they died. Vespasian is even said to have joked on his death bed: 'Alas, I fear I am becoming a god.' While the imperial family often found a place in the heavens it was not usual for a male lover to be turned into a god. Antinous was the exception.

The vast number of images of Antinous that have survived speak to the widespread nature of this cult. His youthful beauty and mass of curly hair made him easy to recognise as his likenesses were dug out of the earth. For young aristocrats on the Grand Tour millennia later, collecting images of the divine Antinous became a hobby. Where they could not buy an original they would commission a copy.

For homosexual Grand Tourists, Antinous proved irresistible. Johann Joachim Winckelmann did more than anyone in the eighteenth century to create a cult of classical art. In one of the most famous portraits of Winckelmann, the great art historian and homosexual can be seen proudly examining an engraving of a statue of Antinous.

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768)

1767, oil on canvas by Anton von Maron (1733–1808)

By the late nineteenth century, Antinous had come to replace Ganymede as the icon of choice for gay art collectors. The troubling paedophilia aspect of the Ganymede myth was in some ways eclipsed by images of Antinous – a handsome young man instead of a cherubic child.

Yet the stories of these two gay icons continued to speak to gay men. Both Antinous and Ganymede were men who were carried out of their humdrum lives by a powerful figure. The love they inspired was not only human – both were turned into divine figures. What the gods hold dear can hardly be wrong, can it? It is no wonder the stories of Antinous and Ganymede spoke strongly to gay men in times when their love was illegal.

Antinous continues to spark interest and artistic creativity today. Images of the youth sell briskly online. The cult of Hadrian's lover can be found in places undreamt of by the grieving emperor. A pink marble obelisk dedicated to Antinous and raised by Hadrian can be found in Rome – but there is another lesser-known monument of Antinous.

In the 'Gay Corner' of the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, you will find the name of Antinous inscribed on an obelisk under the shady branches of a cherry tree.

Ben Gazur, freelance writer