In the mid-1930s, Dame Laura Knight’s interest in communities on the margins of conventional society led her to spend a significant period of time painting at a Gypsy settlement in Iver, Buckinghamshire. The portraits she made there are some of the most compelling of her career.

When I was doing research for the National Portrait Gallery’s 2013 exhibition Laura Knight Portraits, very little was known about the individuals depicted. Given that they were painted within living memory, I felt certain that the sitters could have descendents who might help us learn more about these portraits. Knight’s titles, however, were unhelpfully vague.

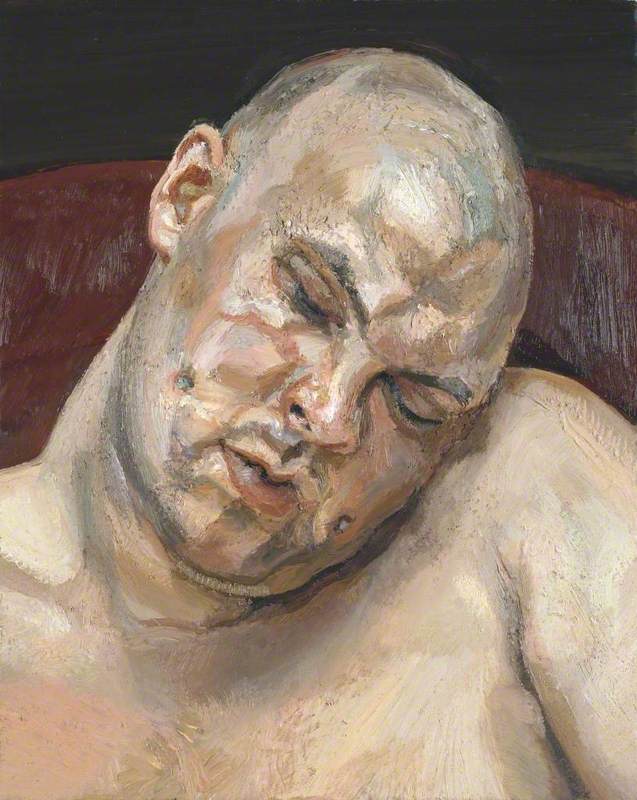

The Gypsy is a highly individual portrait of a man whose expression wavers between aggression and weariness. It was acquired by Tate in 1938, and their archives revealed that this portrait was painted in a single four-hour sitting, but the artist does not identify her model. Fortunately, the painting appears in the Art UK database, which proved to be the source of invaluable information about this portrait, and Knight’s entire Gypsy group.

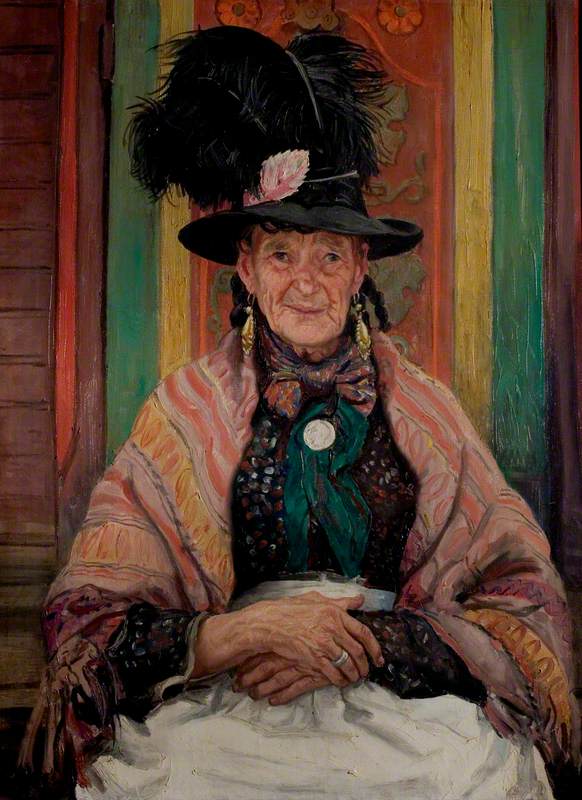

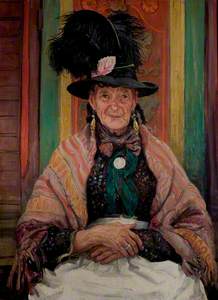

If it were not for Knight’s wonderfully vivid second autobiography, The Magic of a Line (1965), my early research could have stalled for want of clues. In the book, she describes the regular visits she made to Iver, and her favourite sitter: the matriarchal Granny Smith. With the assistance of the local authority Gypsy and Traveller liaison officer, I obtained an invitation to the now permanent site near Iver, where older members of the community had recognised Knight’s sitters through reproductions I had sent in advance.

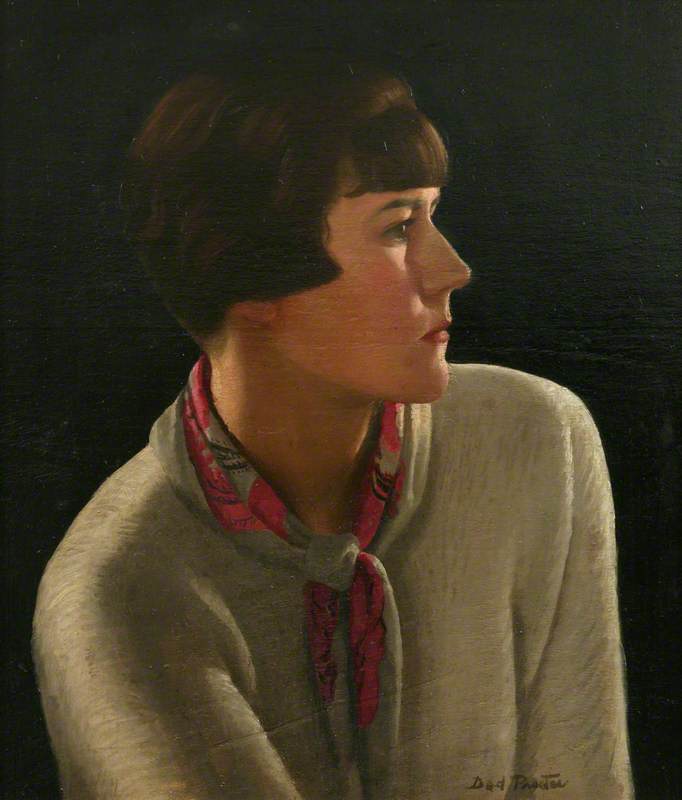

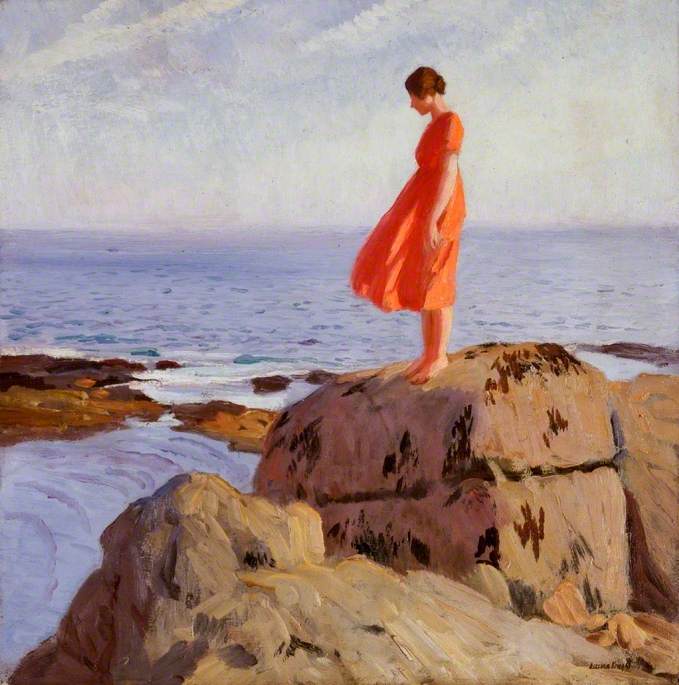

I spent a fascinating morning there, having tea with different families in their fixed mobile homes. I heard about the Gypsy lifestyle in the 1930s, when painted wagons still prevailed. It transpired that the four paintings in the exhibition represent members of the same family; the Smiths. Granny Smith, the model for Knight’s ‘showstopper’ Gypsy Splendour (also known as Fine Feathers) was called Lilo (née Loveridge). The man in Tate’s painting is one of her nine sons, Gilderoy. The enigmatic model whom Knight chose to call ‘Beaulah’ was in fact Freedom Smith, wife of Lilo’s son Harry.

A few months later, and independent of my visit to Iver, Lilo’s great-grandson contacted Art UK to say that The Gypsy showed his great-uncle Gilderoy. Through Tate and Art UK, I was able to correspond directly with Mr Smith, who was researching his family history. He provided more precise dating about Knight’s sitters and some wonderfully vivid anecdotes. He explained that Knight had provided his great-grandmother with the feathered hat she wears in Gypsy Splendour. Thus, she fulfilled the romanticised vision of a Gypsy expected by visitors to the Royal Academy, where the picture was shown in 1939. Fortunately, all this came in time to add to the catalogue and exhibition captions.

These family portraits had never been shown together before, and the group is a remarkable record of an aspect of British rural life just before the Second World War. By inviting contributions from members of the public, Art UK has helped us better understand these unique works of art.

Rosie Broadley, Associate Curator, National Portrait Gallery