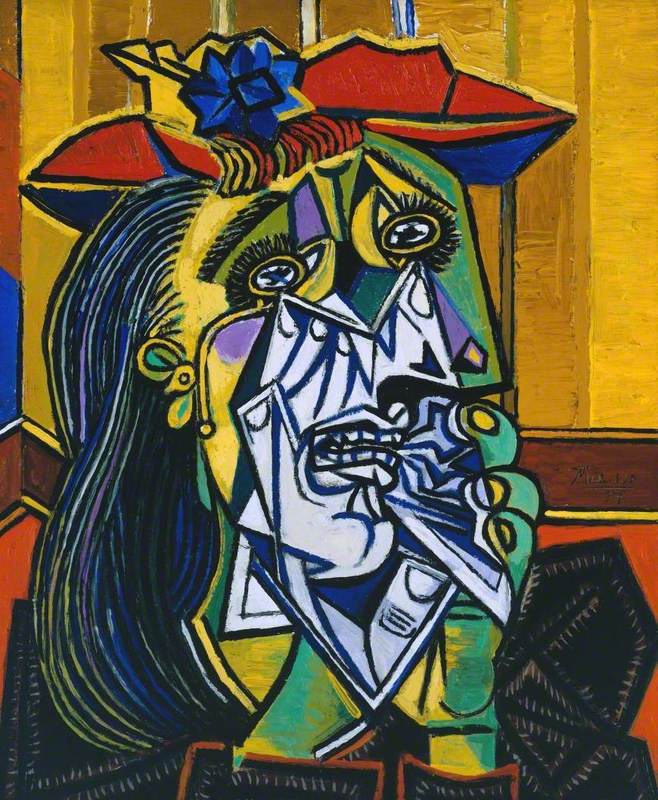

Generally acknowledged to have been the most significant movement in 20th-century art, Cubism was created by Georges Braque (1882–1963) and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) in the period 1907–14. It abandoned the traditional fixed viewpoint which had dominated western painting since the Renaissance, and instead explored a multiplicity of viewpoints to develop an accumulated idea of the subject.

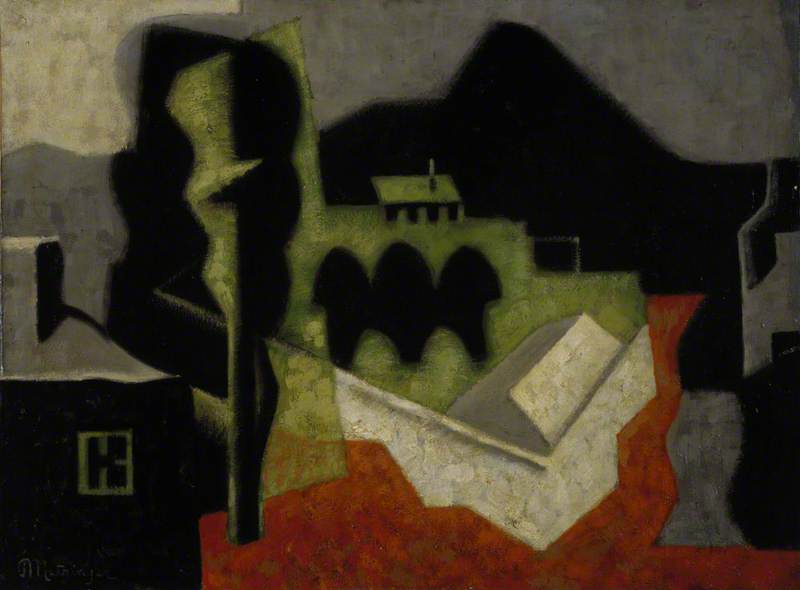

The term was first applied to a group of landscapes painted by Braque at L'Estaque in the summer of 1908 and rejected for exhibition that year at the Salon d'Automne. A member of the selection jury is said to have denigrated them as petits cubes, ‘little cubes’. By 1911 the word ‘Cubism’ had entered the English language. The stylistic genesis of Cubism lay in the late art of Cézanne (whose memorial exhibition had been held in 1907) and African art. These two influences were clearly visible in Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (Museum of Modern Art, New York) of 1906–7. Mature Cubism can be divided into two phases: Analytical (1909–11) and Synthetic (1912–14). The former often involved an analysis of objects into their compound elements and rearranging them on the canvas in a new pictorial order.

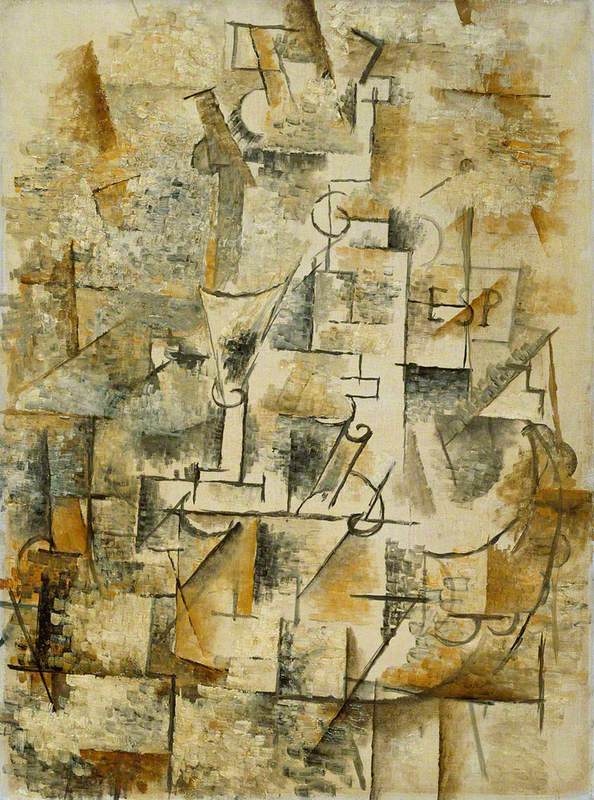

In both Picasso's and Braque's work there is a complex interpenetration of small intricate planes which fuse with one another and the surrounding space. There is little if any sense of spatial recession and colours are muted, often virtually monochromatic greys or browns. Braque was the first of the two to introduce stencilled lettering into his compositions around this time. He also experimented with mixing materials such as sand and sawdust with his paint to create new textures, thereby emphasizing the idea that a picture was a physical object in its own right rather than an illusionistic representation of something else.

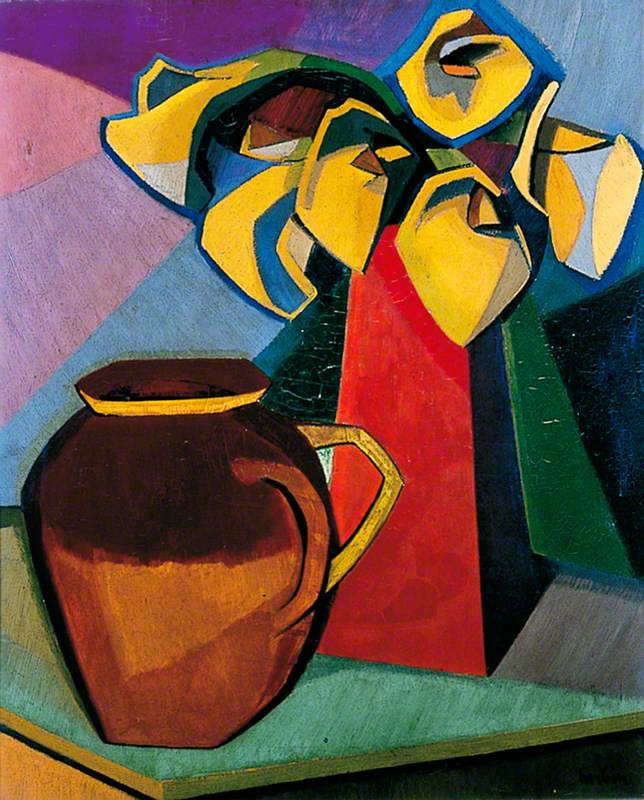

Picasso produced his first collages in 1912, heralding a break with the cerebral near-abstraction of Analytical Cubism. In Synthetic Cubism, in which the Spanish painter Juan Gris also played a vital role, the image was built up from pre-existing elements or objects, rather than being created through a process of fragmentation, as in Analytical Cubism. Colour was also reintroduced. By 1911 Cubism had become the dominant avant-garde idiom in Paris and was first shown in any quantity at the Salon des Indépendants. In 1912 two of the many artists who had been attracted to Cubism, Gleizes and Metzinger, published Du Cubisme, which was translated into English in 1913.

The English-speaking public was acquainted with Cubism by Roger Fry's second Post-Impressionist Exhibition held in London in 1912 and by the 1913 Armory Show in New York, in both of which Cubist works figured prominently. Among the movements which took Cubism as a starting point or an essential component were Constructivism, Futurism, Orphism, Purism, and Vorticism. Cubism was not confined to painting: a significant quantity of Cubist sculpture was produced, not least by Picasso, and, in the brief flowering of Cubism there before the First World War, Prague saw the construction of an innovative form of Cubist architecture.

Text source: The Oxford Concise Dictionary of Art Terms (2nd Edition) by Michael Clarke