Conroy Maddox was born in Ledbury, Herefordshire on 27th December 1912. He was known by the appropriately surrealist nickname of 'Coma', a piece of wordplay using the first two letters of his first and last names, which hints at both the playful aspect of Surrealism, and the dreamlike state that the artists conveyed in their works.

Maddox had a spirited and extroverted personality and strong political opinions that fostered his love for debate. He wore dark suits, had black hair, a military-style moustache and large glasses.

Maddox was a founding member of the Surrealist Art Movement in Birmingham and always remained loyal to the movement, as he believed it the most revolutionary art movement of all. He was introduced to Surrealism in 1935, when he read a book in the Birmingham City Library, consequently abandoning his previously realistic, naturalistic and traditional perspective style. He also met John and Robert Melville, two leaders of the avant-garde in Birmingham, who were already experimenting with Surrealism at the time and taught Maddox about the art movement.

In 1935 Maddox, together with John Melville, created the Birmingham Surrealist group. Soon Maddox's house became a safe haven for creatives and intellectuals, placing him at the centre of pertinent debates and stimulating conversations.

British Surrealism was divided into two camps: the London Surrealists, and the Birmingham Surrealists. The London Surrealists sought to be loosely inspired by Surrealism and did not devote their entire practice to it.

Paul Nash was a prominent figure in the London Surrealist circle. He organised the first 'International Surrealist Exhibition', which took place in London in 1936. Leading continental European Surrealist artists participated including André Breton, Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró and Yves Tanguy, as well as emerging Surrealists based in Britain, such as Eileen Agar, Henry Moore, and Julian Trevelyan. Overall, the exhibition was widely publicised and attracted around 23,000 visitors.

However, a few Birmingham Surrealists, including Conroy Maddox, refused to show at the London exhibition, arguing that most of the British artists chosen for the exhibition were 'anti-surrealists and not Surrealists'. Though Maddox refused to submit any work, he still attended the opening, where he met the likes of Breton, Dalí and Max Ernst. In an interview with Robin Dutt, Maddox noted: '[E. L. T.] Mesens had great glee, mischievous glee in saying, "He [Conroy Maddox] refused to show, you know," and he told Dalí, and Dalí said, "He's quite right, he's quite right."'

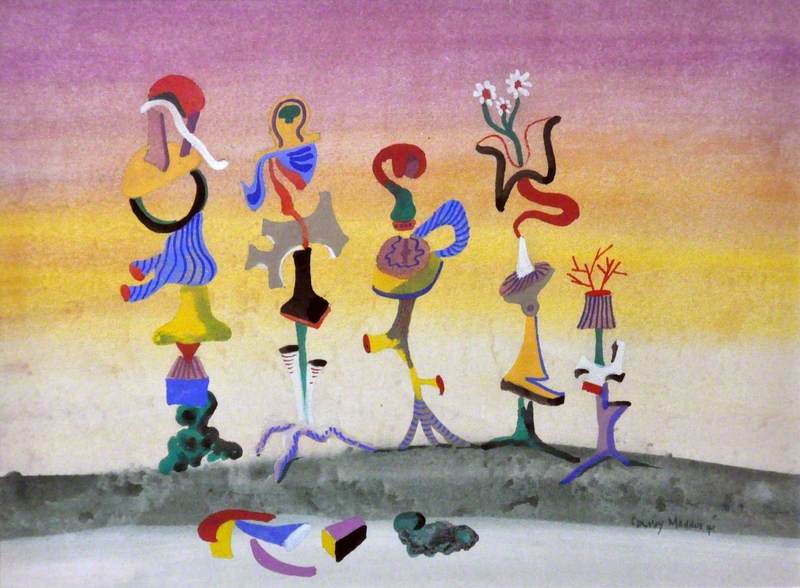

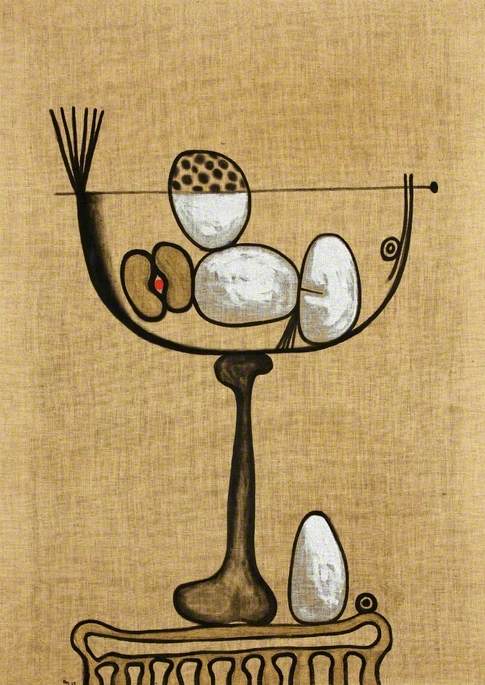

Conroy Maddox was a central figure in the Birmingham Surrealists, and the work Prefiguration (1941) illustrates the influence of artists such as Joan Miró and Salvador Dalí. Miró's art is characterised by brightly coloured, biomorphic shapes, akin to those in Prefiguration. This work by Maddox demonstrates the Surrealists' agenda of creating strange, perplexing works that feature dream-like scenes.

There are countless interpretations of the work, which is what Maddox promoted, as he never revealed the meaning behind his art. As Maddox said in 2001, 'A surrealist does not know what he is doing. Dalí didn't know what he was doing. I don't know what I'm doing. Something happens and it develops, but you don't analyse it. By doing that you destroy a surrealist image.'

Prefiguration could be depicting five figures walking across a land, below them a body of water, or it could be depicting five figures that are rooted into the floor and swaying back and forth with the wind. This work furthers the viewer's imagination and asks them to tap into their unconscious to attach a meaning or story to this work.

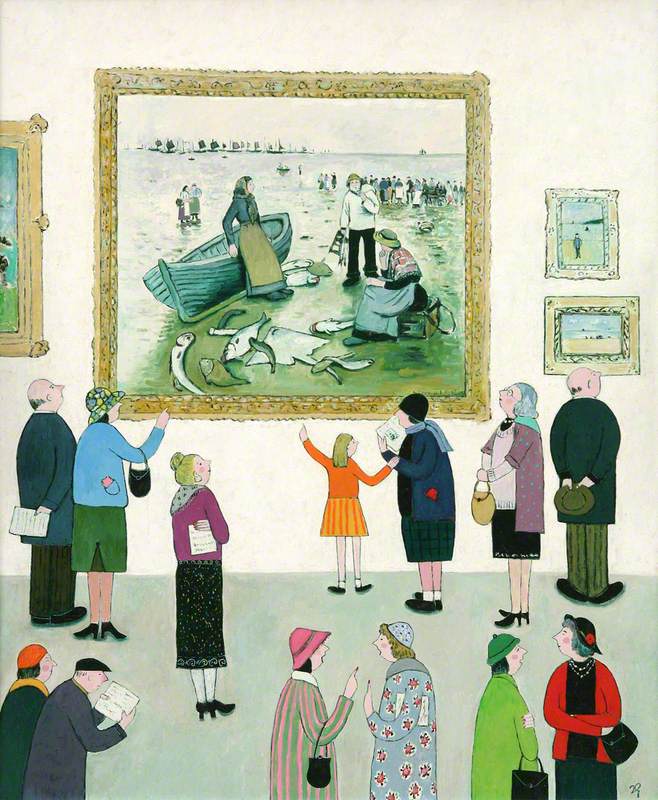

The Lesson

1938/1970 by Conroy Maddox (1912–2005). Shown as part of Dulwich Picture Gallery's 2020 'British Surrealism' exhibition

The Lesson was possibly one of Maddox's earliest works. It has been understood that the figure sitting down is observing his younger self. This 'younger self' is covering his eyes, as to not observe the scenes taking place in the windows in front of him. There is a large eye staring out from the top left window, hinting at the Surrealist emphasis on the idea of looking, and constantly questioning how we observe the world around us. Further, Surrealism is often witty and uses humour – however, to Surrealists, humour is also a mode of ethics and a form of commentary.

Maddox dated The Lesson 1938, although he probably painted it in 1970. Maddox's earlier works were more valuable than those he painted after the Second World War. Thus, through this unclear dating, he played a game with collectors and art historians, as well as critiqued the powerful structure of the art market.

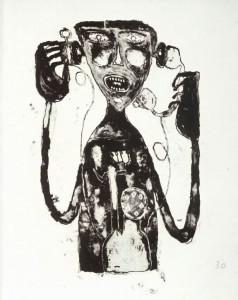

Onanistic Typewriter I

1940 by Conroy Maddox (1912–2005). Shown as part of Dulwich Picture Gallery's 2020 'British Surrealism' exhibition

Conroy Maddox did not only embrace painting. Onanistic Typewriter I (1940) is a ready-made object, a typewriter rendered useless by the applique of spikes on the keyboard. This work was greatly influenced by Man Ray, specifically his piece Cadeau (meaning 'Gift') – a flat-iron with brass tacks glued down the centre.

The 'Surrealist object', which became popular in the 1930s, used a combination of objects that challenged reason in order to push the viewer into their creative subconscious. As André Breton noted, 'To aid the systematic derangement of all the senses... it is my opinion that we must not hesitate to bewilder sensation...'

Most objects used, such as the typewriter in Onanistic Typewriter I were everyday, mass-produced objects, yet removed from their expected context and defamiliarised. The Surrealistic object was linked to Freud's concept of the 'fetish', where the viewer projects one's desires upon an object, thus turning an ordinary object into a fetish. The Onanistic Typewriter is amusing, however also frightening, as one can almost feel the pain and see the blood when imagining using it.

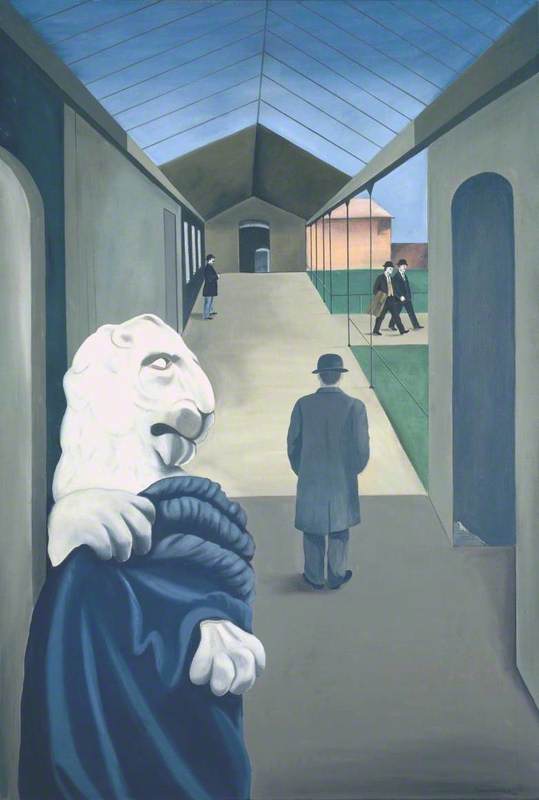

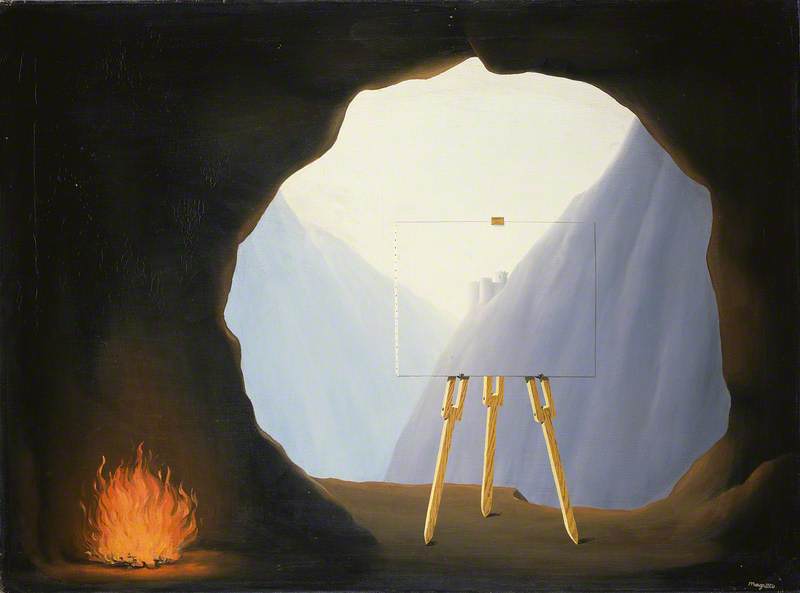

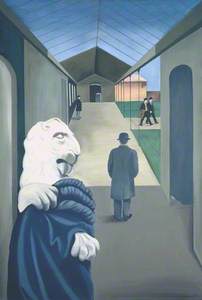

In Passage de l'Opéra (1970) Maddox draws inspiration from Giorgio de Chirico's infamous deep-perspective style. The elongated perspective, the indoor/outdoor room, and the open doors on the far end of the room, all create a view that spans endlessly into the distance. Also, the painting features bowler-hatted men, which Surrealist painter René Magritte was notorious for depicting. In the foreground, there is a strange lion statue that appears to be holding a drape.

The work is said to be inspired by a novel by the Surrealist writer Louis Aragon. As Maddox noted, 'Aragon points out that his wanderings around the Passage de l'Opéra were without purpose, yet he waited for something to happen, something strange or abnormal, so as to permit him a glimpse of a new order of things. Such experiences... were conducive to Surrealism's attraction to the marvellous.'

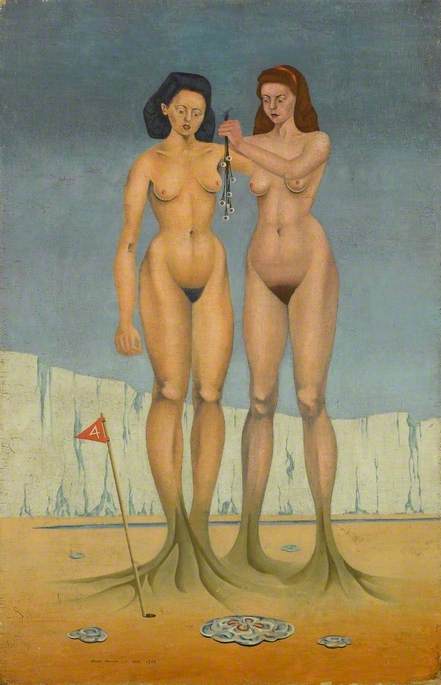

Later on in his career, Maddox experimented increasingly with collage techniques that were popular amongst Surrealist artists. Surrealists saw collage as a way to gain access to the unconscious mind, through combining different, often juxtaposing things and creating a new entity. In The Theorist (1948), the figure is made up of absurd combinations of different but recognisable things. It causes the viewer to reshape reality, demonstrating the power of the mind's ability to make a new world out of unexpected combinations of already existing objects.

Sigmund Freud's ideas on psychoanalysis were extremely influential to Surrealists. Freud believed that dreams are coded expressions of fears and desires. The Surrealists believed that through techniques such as collage and automatism, these fears and desires could be expressed and would create revolutionary images.

In conclusion, as Maddox said, 'So there was... maybe you might say there was an element of the shock tactics about this, of course, but that was quite valid because one wanted to jerk the people out of their ordinariness, this confrontation with reality which is a bit elusive when you think of it, you know, what is reality? The Surrealists have always questioned it.'

The Surrealist art movement asked more questions than it answered and left the viewer perplexed and in a challenging position. Maddox was adamant about not explaining his works, forcing the viewer to try and come to terms with the image. His works reject a rational vision of human life, enticing viewers into using their imagination and intuition in order to transform experience.

Anna Niederlander, The Reiff Collection

Further reading

Barber Institute of Fine Arts, 'Conroy Maddox and Birmingham Surrealism', YouTube, 2014

Peter Davies, 'Conroy Maddox', Independent, 2005

Tim Hilton, 'Conroy Maddox', The Guardian, 2005

J. H. Matthews, 'Surrealism and England', Comparative Literature Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 1964

MoMA Learning, 'Surrealism', MoMA, accessed 20th March 2021

Levy Silvano, The Scandalous Eye: The Surrealism of Conroy Maddox, Liverpool University Press, 2003

The British Library, 'National Life Stories – Artists' Lives: Conroy Maddox interviewed by Robin Dutt', 1996–1998