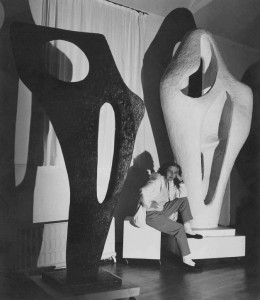

Barbara Hepworth is enjoying increasing popularity. It is not just her work that intrigues, but also her career, as a female sculptor in the years when that seemed remarkable to male critics.

Barbara Hepworth at Work on the Armature of a Sculpture

1961

Ida Kar (1908–1974)

Temporary exhibitions can make it easy for us to get a sense of an artist's production by grouping their works together in one place at one time, but the joy of the Art UK database is that you can do much the same thing yourself. Finding out where an artist's works are located is closely related to tracing their biography, and I want to give a taste of this here.

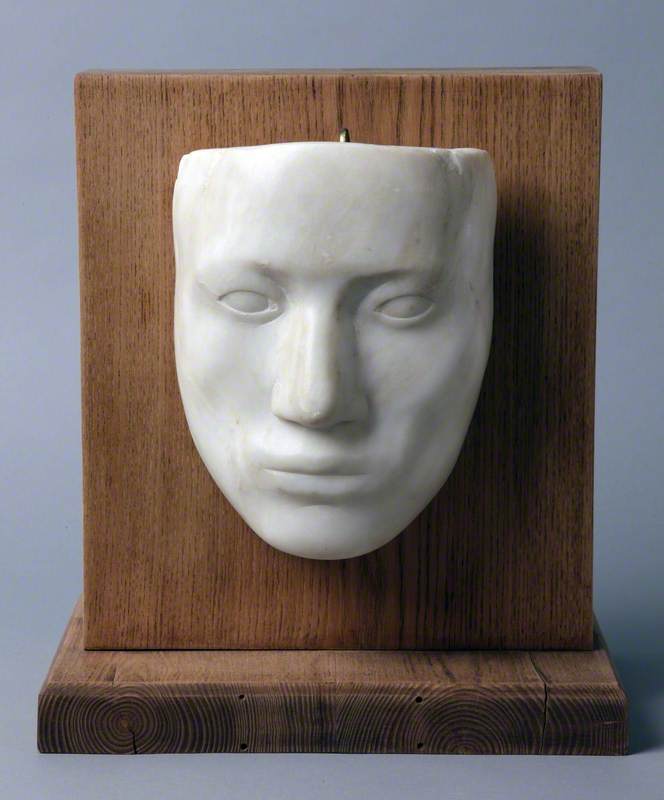

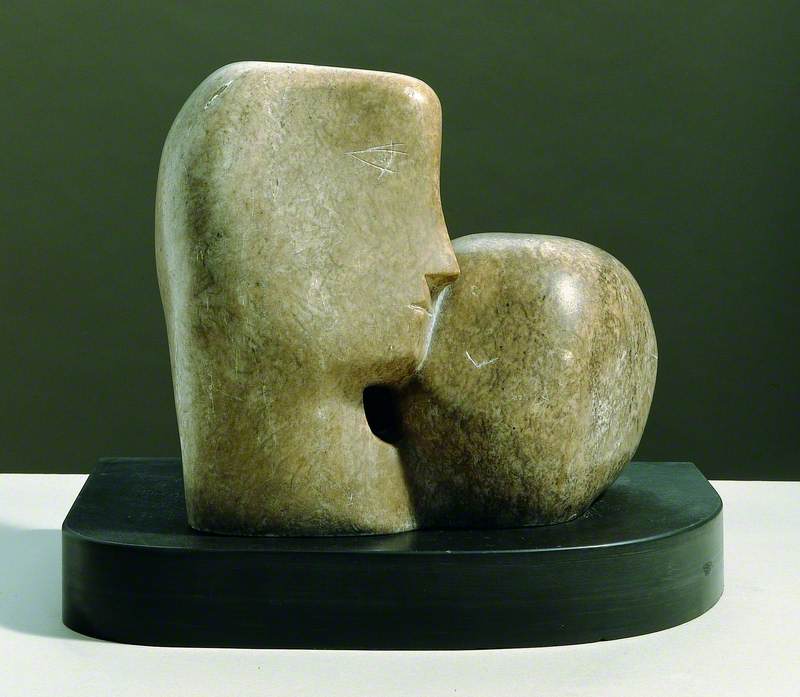

Hepworth was born in Wakefield and thus it is not all surprising to find that her local art gallery, now named The Hepworth Wakefield, has a small but important selection of her works, especially those from the beginning of her career.

She then studied in Leeds, and the fact that Leeds Museum showed her work in Temple Newsam House during the war meant that they (especially Director Philip Hendy) established a relationship with the artist, from whom they went on to acquire a handful of key pieces.

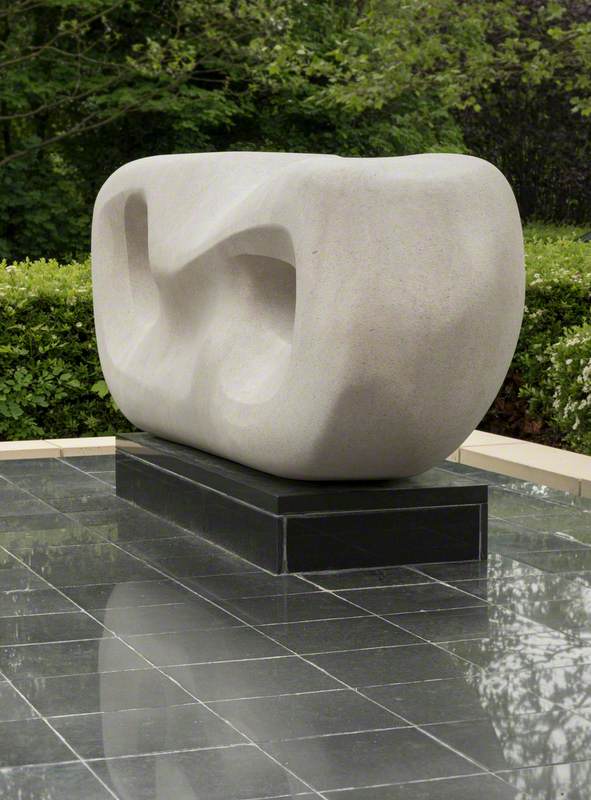

Other important works, bought quite early and during the artist's lifetime, are spread out among British municipal galleries: Aberdeen, Birmingham, Leicester, Manchester.

A number of significant individuals figure in this work-life story. When Hepworth was struggling with childcare she was supported by Margaret Gardiner who, at the end of her life, left her collection to the Pier Arts Centre in Stromness, Orkney.

Since then the Pier has had an important connection with Hepworth. At a later stage, Hepworth found the support of Joseph Hirshorn, the American mining tycoon whose collection was enshrined in the Hirshorn Museum in Washington DC.

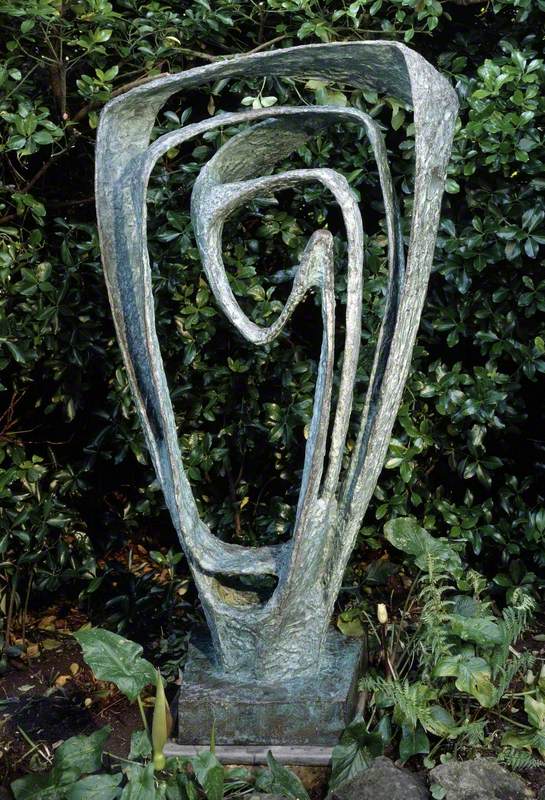

Two other figures represented a more expressive understanding of what Hepworth was trying to do. The Secretary-General of the United Nations, Dag Hammarskjöld, was immensely busy, but found time to write and visit, and this relationship led to the unlikely presence of Hepworth's works in Sweden, and at the United Nations itself (with a smaller version of the UN sculpture in Battersea Park).

Another critical relationship outside Britain was with Bram Hammacher, the art critic who ran the Kröller-Müller Museum in the Netherlands from 1947–1963, which maintains a permanent showing of her work in the Rietveld Pavilion.

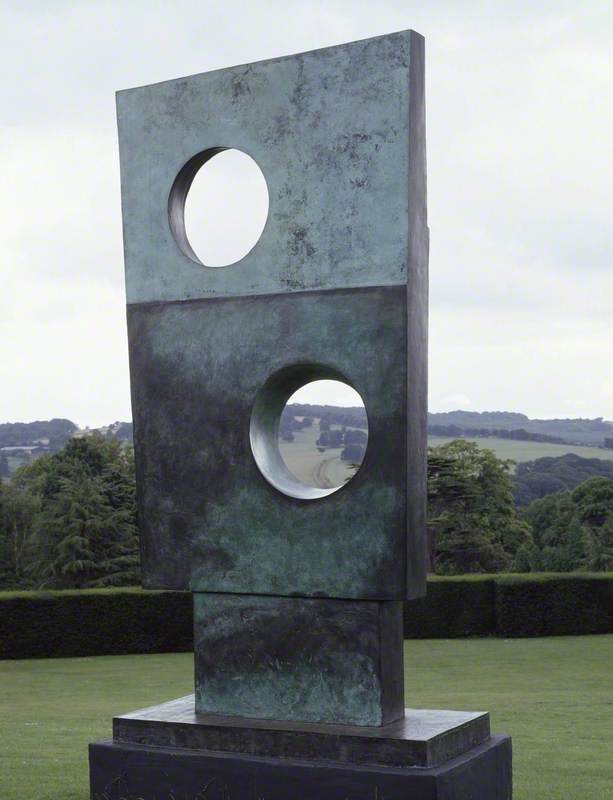

After the war, Hepworth was one of the British artists supported by the newly formed Arts Council and toured by the British Council. For these purposes, the Councils bought works, especially in bronze, but also drawings, which could travel relatively easily.

These works may normally be based in Yorkshire, at the Arts Council's Longside Gallery, or in London, but are also equally likely to be on tour, even (or especially) now.

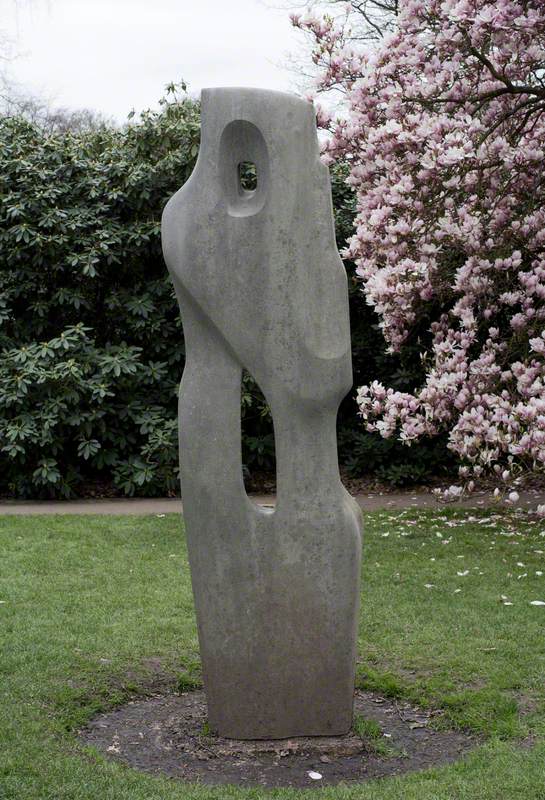

Hepworth did not make a lot of public works, but most of her commissions are still in place. Public sculptures which very much represent the spirit of rebuilding that went with the creation of the post-war Welfare State include those for educational buildings in Hatfield and the re-siting of Southbank commissions at Kenwood House, Harlow and St Albans.

Later, commercial, commissions include the wall sculptures on John Lewis, Oxford Street in London, and on the Cheltenham and Gloucester Building Society in Cheltenham.

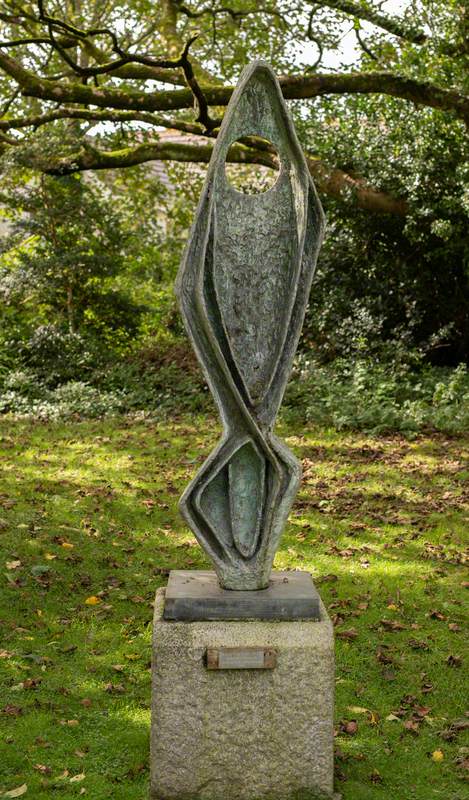

Theme and Variations

1969–1972

Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975) and Morris Singer Art Foundry Ltd (founded 1927)

Public commissions which have been removed from their sites and subsequently sold include those which were Rosewall in Chesterfield (Royal Mail) and Meridian on High Holborn (models for which are in the collections of the Tate and New College, Oxford).

In the last decade of her life, Hepworth became a trustee of the Tate Gallery. This had a significant effect on her legacy. She twice gave works and archive materials to the Tate in her lifetime, and after her death in 1975, her son-in-law, the then Director, created the Barbara Hepworth Museum in St Ives in her former studio. He was later to gift a group of plasters to the nascent project in Wakefield which absorbed the former Wakefield Art Gallery, where this story started.

Hepworth's choices about her work and her life – where to live, with whom to work, and how – mean that her work is now well represented at the very extremities of Britain, from its south-western corner to the north-eastern isles, with a solid anchor in the middle, in London and Yorkshire. Appreciation from certain key supporters abroad expands her 'footprint' to Sweden, the Netherlands and the United States.

Penelope Curtis, curator and art historian and author of British Artists: Barbara Hepworth