Capturing a fleeting moment in time is a skill mastered by, and rightly attributed to, artists such as Edward Hopper, Edgar Degas and L. S. Lowry. However, another artist who shone a spotlight on life's ephemera is Clare Atwood – a British painter of portraits, landscapes and still life, but whose depictions of interiors were arguably the most memorable of all her work.

Clare Atwood was born Clara Atwood on 14th May 1866 at Hermitage Cottage in Richmond, Surrey. She was the only daughter of architect Frederick Atwood and his wife Clara, after whom she was named. She shortened her name to Clare but would later be known as 'Tony' to her friends and associates.

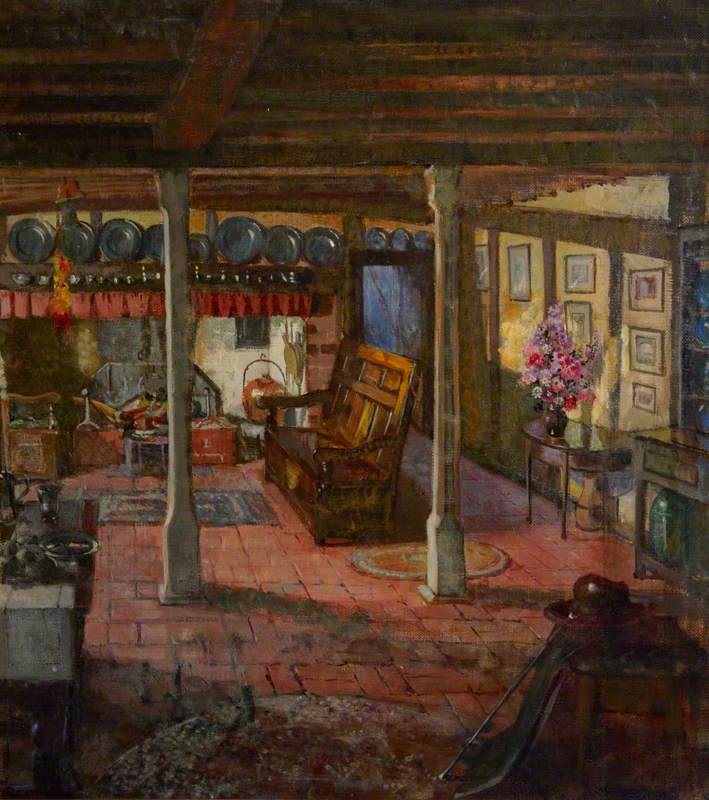

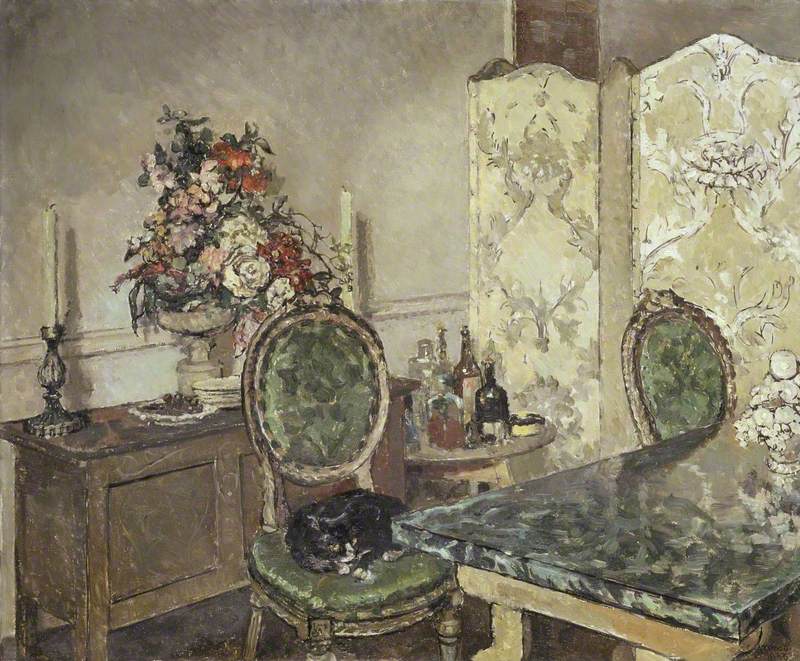

The Dining Room at Smallhythe Place

c.1920

Clare Atwood (1866–1962)

Atwood studied at Westminster School of Art, with artist Leonard Charles Nightingale (1851–1941) as her teacher. She went on to attend the Slade School of Fine Art, where she was taught by Professor Frederick Brown (1851–1941), a founder member of the New English Art Club. Atwood first exhibited with the New English in 1893, becoming a member in 1912 and enjoying a lifelong association with the group. Another of her teachers at the Slade was Henry Tonks (1862–1937), a former surgeon who switched careers to become an artist. A celebrated painter of interiors, Tonks was clearly a major influence on Atwood's own compositions.

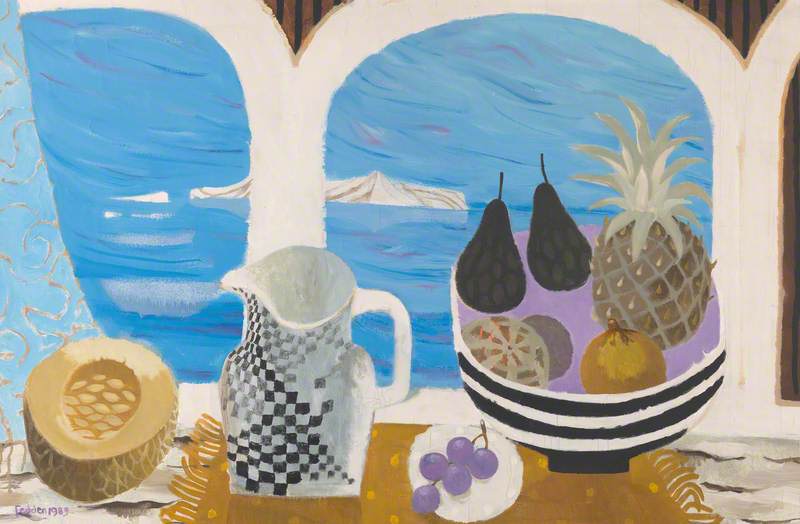

Dish of Apples and a Pear

1915

Clare Atwood (1866–1962)

In 1895, she moved into a studio overlooking the River Thames, opposite St Paul's Cathedral. Her building was next door to the house in which Christopher Wren had lived whilst the cathedral was being built.

As well as the New English Art Club, Atwood exhibited with the Women's International Art Club, and at the Royal Academy. A review published in The Athenaeum in 1908 praises her 'wonderfully eloquent rendering of ripe Stilton cheese' in one show, but the most glowing critiques were reserved for her studies of interiors.

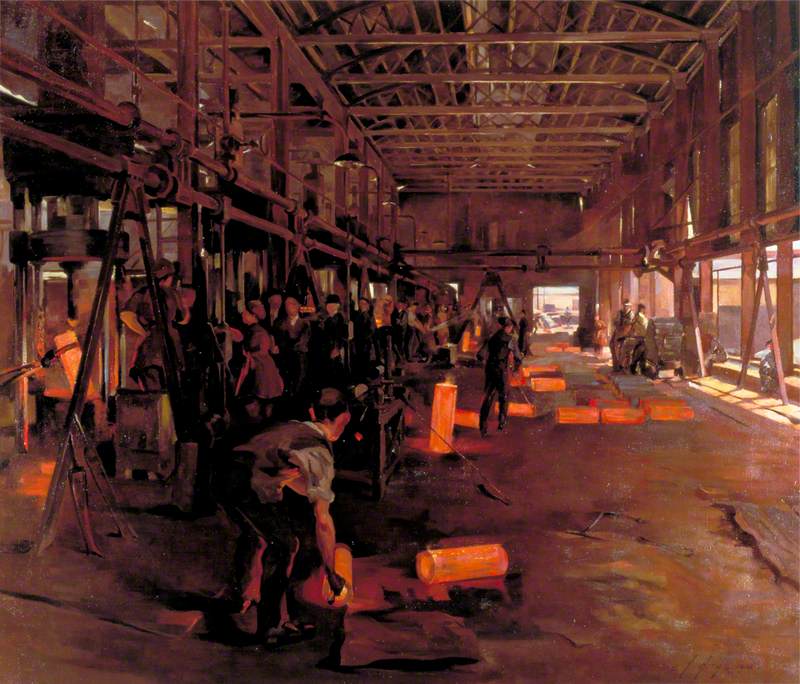

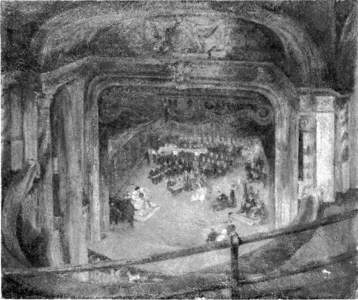

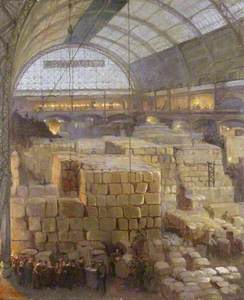

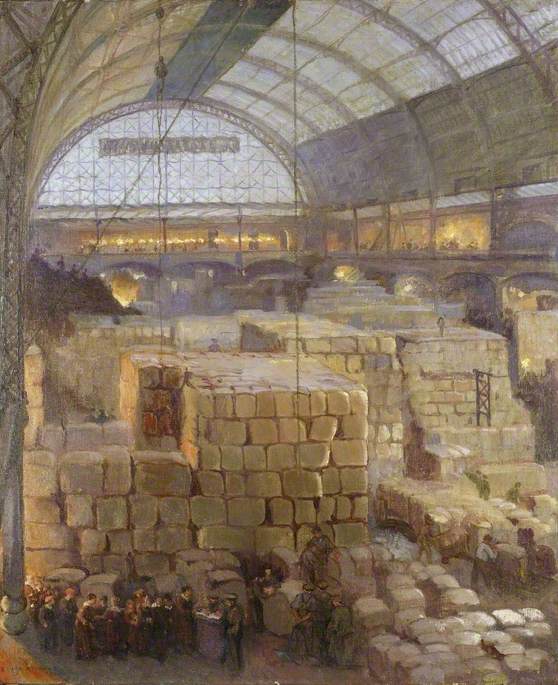

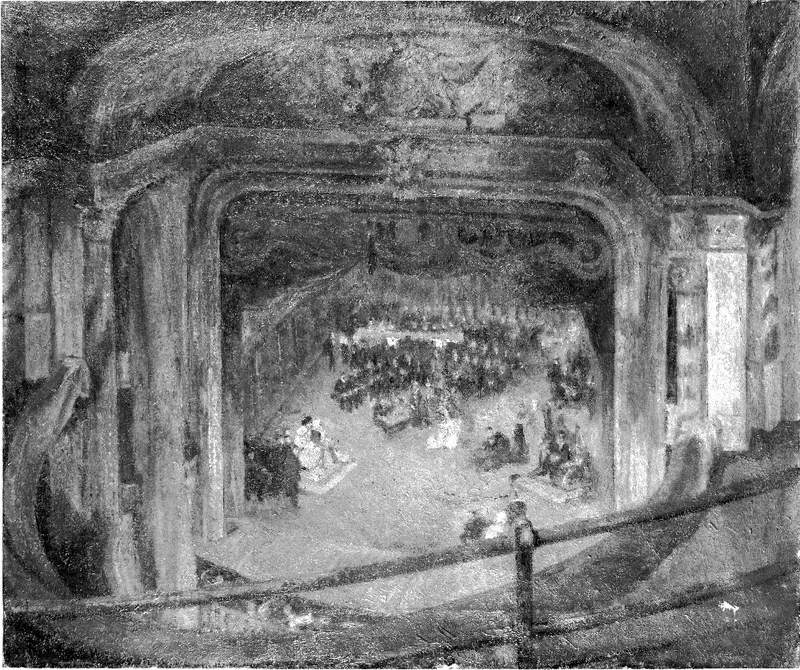

Her painting of Airedale Foundry was described in The Speaker (1906) as 'a fine essay in interior lighting and tonality', while in 1910 The Spectator highlighted two of her works: 'A Grey Day in the Market is beautiful not only for its mother-of-pearl reflections, but also for its feeling of the spaciousness of the inside of a great building. Rehearsal is a satisfying harmony of a dim and deep-coloured theatre lighted only from the orchestra. In both these works we welcome the feeling of a fine painter.'

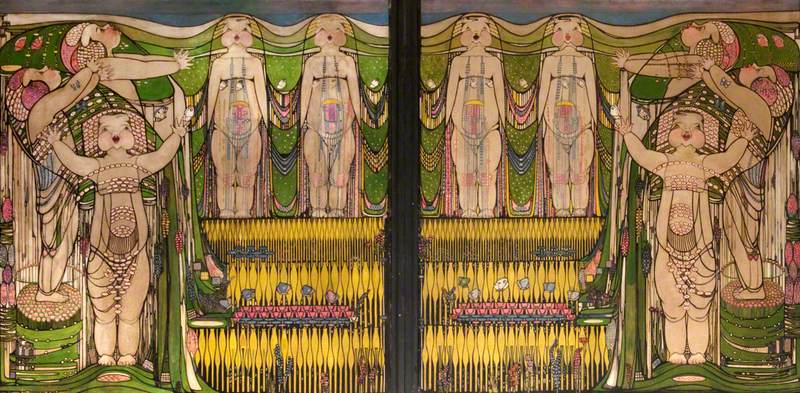

Interior of the Coach-Wheelwright's Shop at 4 1/2 Marshall Street, Soho, London

1897

Clare Atwood (1866–1962)

Her painting Interior of the Coach-Wheelwright's Shop (1897) depicts a busy scene from the workshop that made the wheels for various royal carriages. There is a generous sense of perspective created by the placement of timber beams and posts, framing the workers and drawing the viewer into their industrious world.

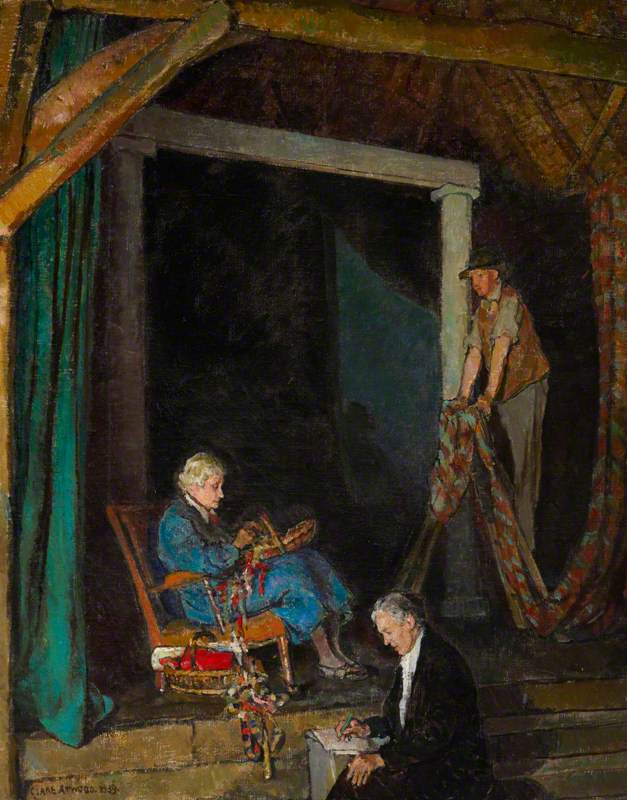

In the same vein, Atwood often used a proscenium arch to frame her studies of theatre interiors such as in a painting of Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree at His Majesty's Theatre (1910) and The Rehearsal, Drury Lane (1917). Combined with a view of the auditorium or balcony in the foreground, the arch provided a focal point and a sense of space, allowing the viewer to witness a moment in time without disturbing it too much.

Every one of Atwood's interior scenes portrays a hive of activity, yet there is a stillness about her work which is very likely a reflection of her own nature. The author and garden designer Vita Sackville-West described her friend 'Tony' as 'a person on her own'. She wrote: 'She is a peacemaker, she restores the balance. She never talks about herself; yet one is always conscious of her presence as a soothing influence.'

When Atwood's Bankside studio was bombed during the First World War, she moved to Bedford Street, Covent Garden, into a flat she shared with producer and actress Edith 'Edy' Craig and writer Christabel 'Chris' St John. Craig was the daughter of acclaimed Victorian stage actress Ellen Terry and both women were active suffragists.

Atwood entered into a happy, long-term relationship with the pair, and the self-styled 'three musketeers' were friends with a circle of women artists and writers including Vita Sackville-West, her lover the author Virginia Woolf, lesbian novelist Radclyffe Hall and her partner Una Troubridge. Their creative network often socialised together at the trio's Kent residence, Priest's House – in the grounds of Smallhythe Place, home of Ellen Terry – where Atwood also had a studio.

The Terrace outside the Priest's House

1919

Clare Atwood (1866–1962)

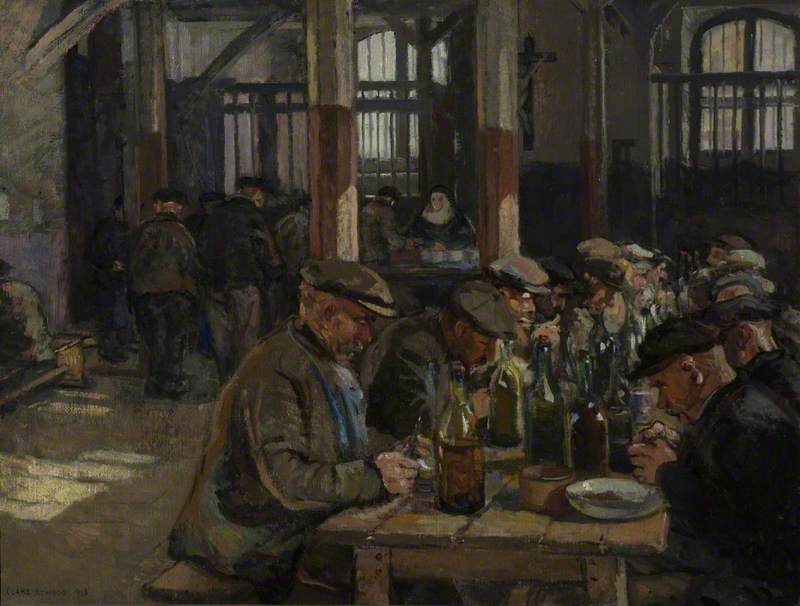

In 1917, Atwood was commissioned by the Canadian Government to produce a painting about the experiences of the Canadian Expeditionary Force in England. In 1920, four of her paintings commemorating the women's war effort were acquired by the Imperial War Museum, including Christmas Day in the London Bridge YMCA Canteen (1920). In Beyond the Battlefield, Catherine Speck remarks upon the hints of purple and green in the scene, suggesting a nod to the suffrage movement.

After the war, Atwood's focus turned increasingly to subjects theatrical.

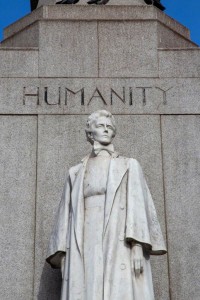

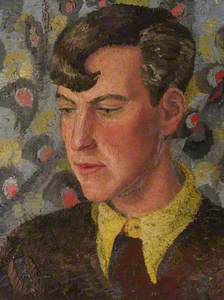

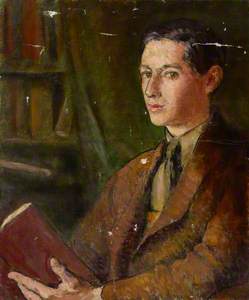

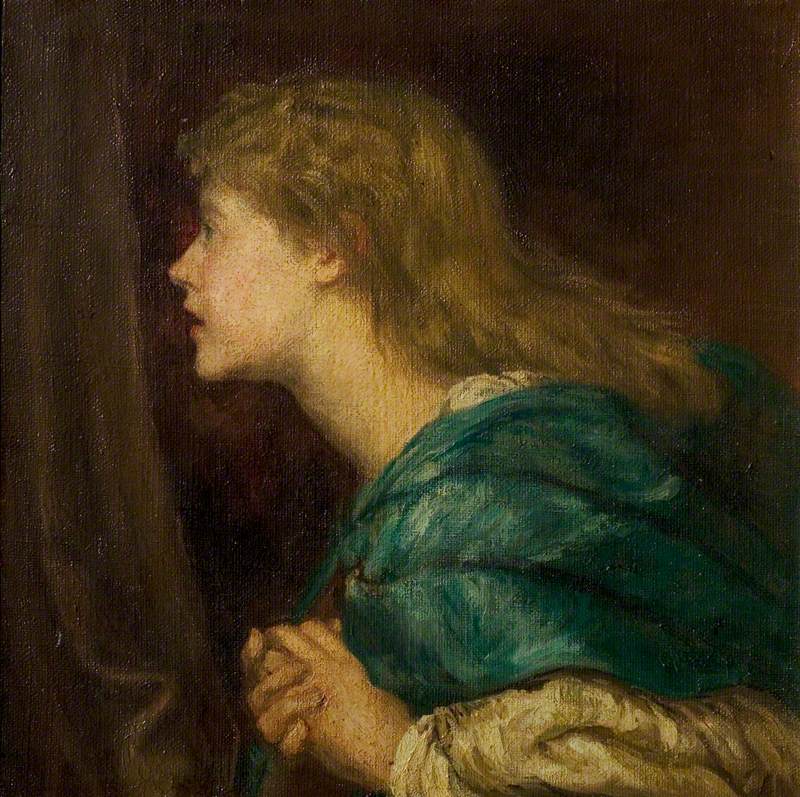

Eleanor ('Nellie') Terry (1904–1975)

c.1918

Clare Atwood (1866–1962)

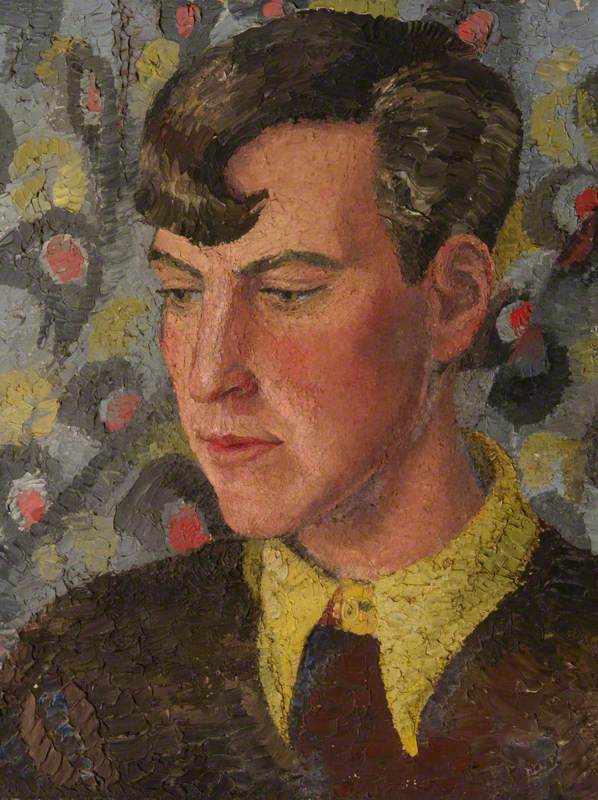

She painted portraits of Ellen Terry at various stages of her life.

Dame Ellen Terry (1847–1928), Aged 79

1926

Clare Atwood (1866–1962)

She also designed props and painted scenery for the Pioneer Players, a theatre company run by Craig.

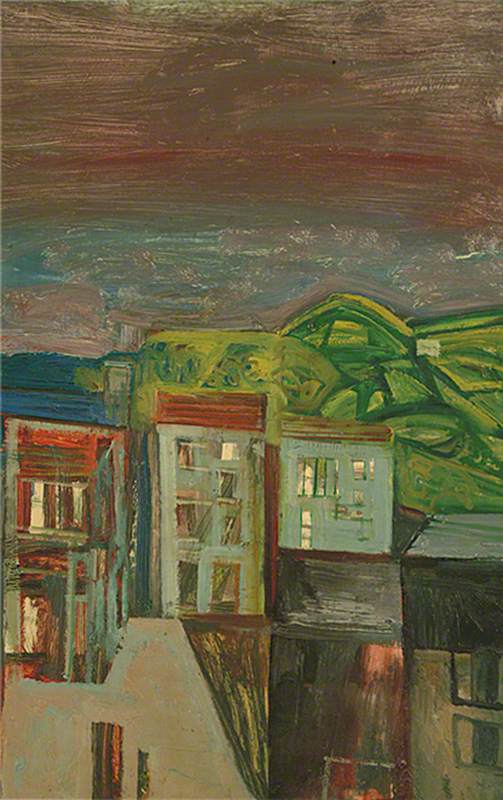

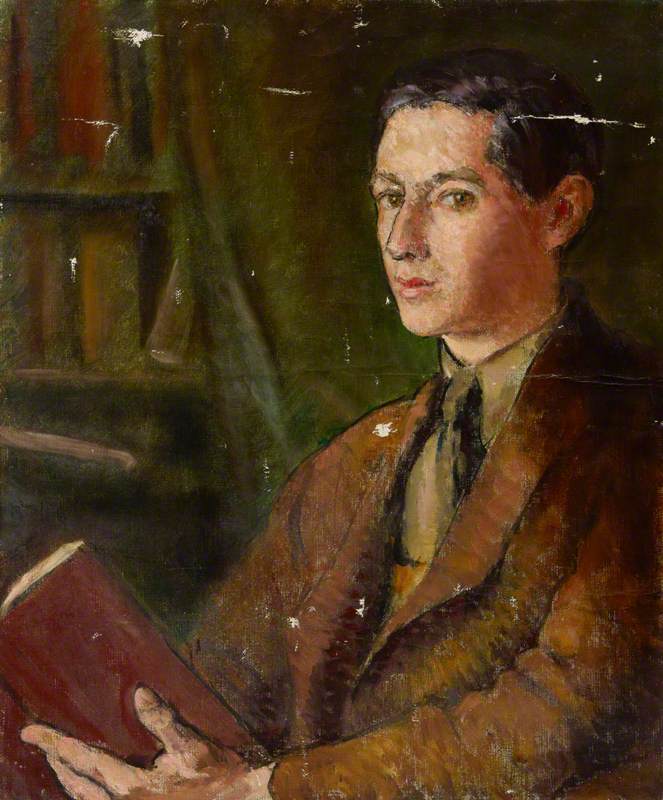

Sunday, St Paul's Church, Covent Garden

1918

Clare Atwood (1866–1962)

During this time, her paintings of Sunday, St Paul's Church, Covent Garden (1918), known as the actors' church, and John Gielgud's Room (1933) were exhibited at the Royal Academy, in 1932 and 1933 respectively.

Despite her artistic talent and high-profile connections, very little has been written about Tony Atwood the person, which is rather a pity. In A Strange Eventful History, Michael Holroyd writes that Atwood was 'in many ways an unexceptional person... she took no exception to anything, seeing all points of view, never speaking of herself.'

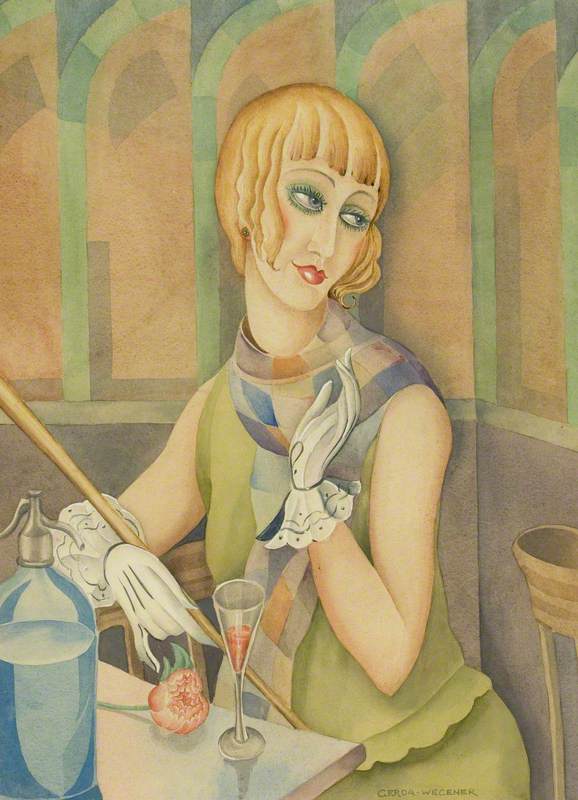

Self Portrait in a Hat with a Basket of Vegetables

1951

Clare Atwood (1866–1962)

The only glimpse we have been given into Atwood's self-perception is by way of her Self Portrait in a Hat with a Basket of Vegetables (1951), where she is shown in her customary masculine clothing – but perhaps that is the way she wanted it to be.

Kay Carson, writer

.jpg)