Paintings of cows are often mocked at by academics. Cows certainly never featured at the Courtauld Institute of Art in the teaching of Anthony Blunt and his august colleagues. In my own studies I never found any French seventeenth-century cows but there were plenty in Dutch art of the same period.

A Distant View of Dordrecht, with a Sleeping Herdsman and Five Cows ('The Small Dort')

about 1650-2

Aelbert Cuyp (1620–1691)

So I returned to Kent in search of some really good cows and specifically to Canterbury. On my 1974 visit to that venerable city, perhaps thinking too much of St Augustine I was greeted by a shocking sight. The entire collection of Old Masters had been packed into a cupboard, and the then curator was neither able or willing to let me look at them. I recorded this failure in the preface to my Old Master Paintings in Britain. So we had to wait a generation for the first printed catalogue by the Public Catalogue Foundation.

Now it was already known that Canterbury was the place of residence of one of the very best cow painters, one Thomas Sidney Cooper (1803–1902). For almost 80 years he painted every conceivable cow in every possible position that a cow could find itself in. The delightful landscape settings often included Canterbury in the background. Cooper was the subject of a catalogue raisonné by Steven Sartin in 1976 and therefore Canterbury’s cupboard proved useless as a defence against knowledge.

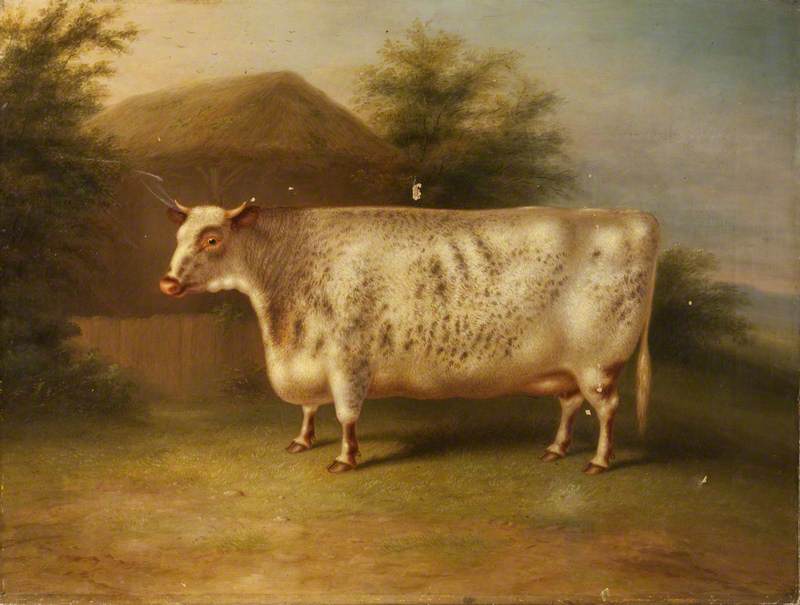

Separated, But Not Divorced (The Bull)

1874–1882

Thomas Sidney Cooper (1803–1902)

What looks like one of the largest cow pictures in existence is by Cooper and it overwhelms by its size. The life-size Separated, But Not Divorced (The Bull), looks at least as large as the magnificent The Bull by Paulus Potter in the Mauritshuis, The Hague. It is hard to imagine that Cooper was born before the Regency of King George IV and lived into the twentieth century. The Pre-Raphaelites and Impressionism passed him by and it still needs a bit of courage to cope with Cooper.

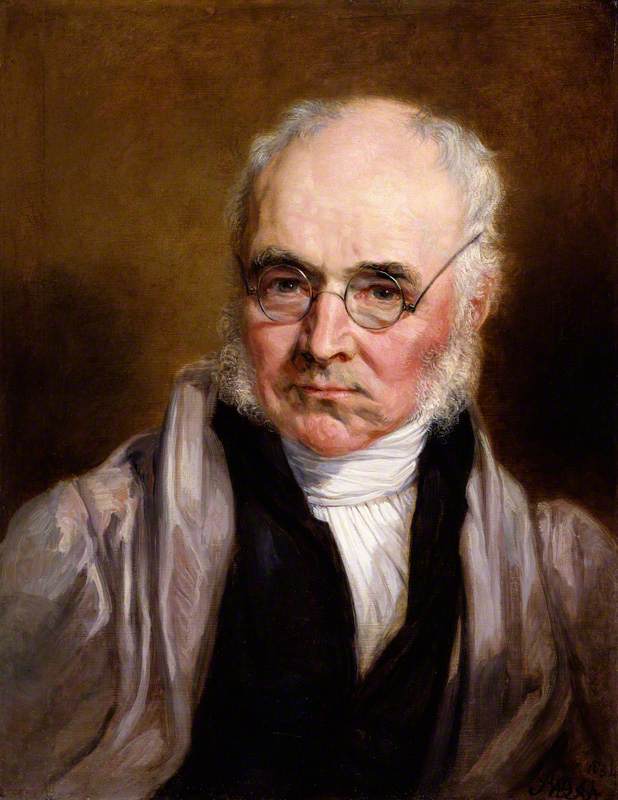

Christopher Wright, Art UK advisor, art historian, artist and author of numerous catalogues of Old Master paintings in Britain