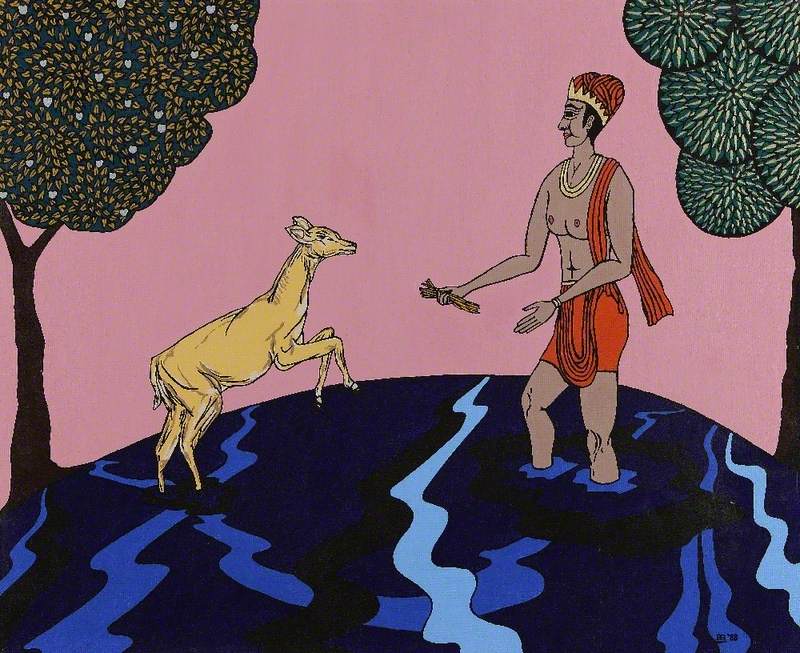

The term 'metamorphosis' is elusive and multi-layered. Biologically it signifies a complete change of physical form, though it also describes a change by supernatural means and can relate to the inner psychological transformations of being and identity.

Apollo and Daphne

probably 1470-80

Antonio del Pollaiuolo (c.1432–1498)

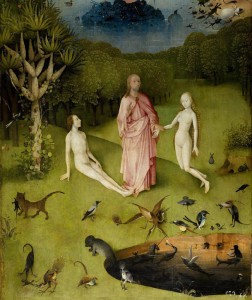

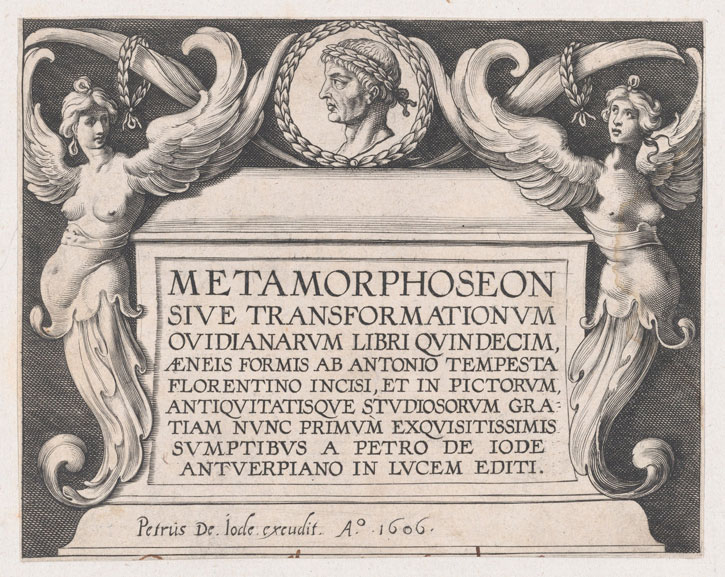

These aspects are incorporated into the epic poem Metamorphoses by the ancient Roman poet known as Ovid (43 BC–AD 17/18). Within this work, written in Latin around the end of the first century BC, the poet weaved stories together with themes of psychological and physical transformation. He considered timeless topics such as romantic and maternal love, pursuit and punishment, ambition and downfall.

Ovid's Metamorphoses remains one of the most potent sources of mythological narrative and is among the most referenced and inspirational poems in European literary history; it is more widely illustrated than any other literary source, written or orally transmitted (except for the Bible). Its influence on many European artists across centuries has always held a particular fascination for me.

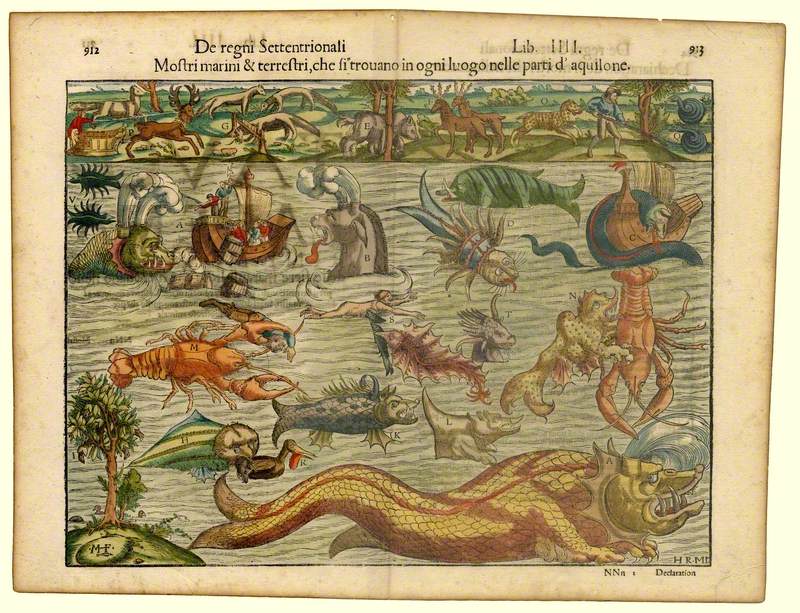

Titlepage to Ovid's 'Metamorphoses'

1606, print etching by Antonio Tempesta (1555–1630) published by Pieter de Jode I

The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, on the University of Birmingham's Edgbaston campus, has a strong collection of works that reflect the influence of this poem. A number of these were selected for a small display inspired by Metamorphoses, which I researched during the UK's first lockdown last spring. The fact that I was researching and curating a display around the poem during this lockdown gave the process extra resonance. I often wondered what Ovid would have made of our situation, and what we were being turned into by the pandemic.

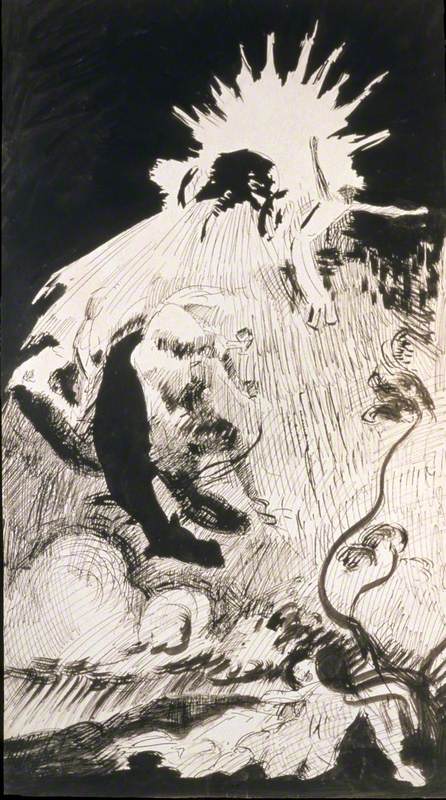

The display, called 'Changing Shapes: Metamorphosis in Art', opened in autumn of 2020. It contains a selection of The Barber's 800+ prints and drawings, ranging from mid-sixteenth-century Flemish etchings to an early twentieth-century drawing by French painter André Derain, and a 1950s Surrealist print by German artist Max Ernst.

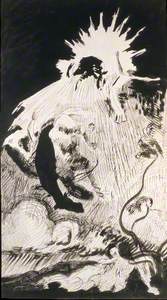

La Chute De Phaëton (The Fall of Phaeton)

c.1905

André Derain (1880–1954)

With such a wealth of Barber works to choose from, it was a welcome challenge to pick just eleven for the display. I was keen to begin with some of the oldest works, partly to show more traditional representations of Ovid's poem, but also to compare depictions of some of his most well-known tales, such as that of Apollo and Daphne, across centuries. This allowed me to consider how some of the wider cultural and social implications of the time impacted artists' interpretations and, with this, how such works of art are part of a wider network of meanings that can shift-shape and alter across time and place. Approaching the interpretation in such a way felt particularly apt for the display, considering the theme of transformation at the core of Ovid's poem.

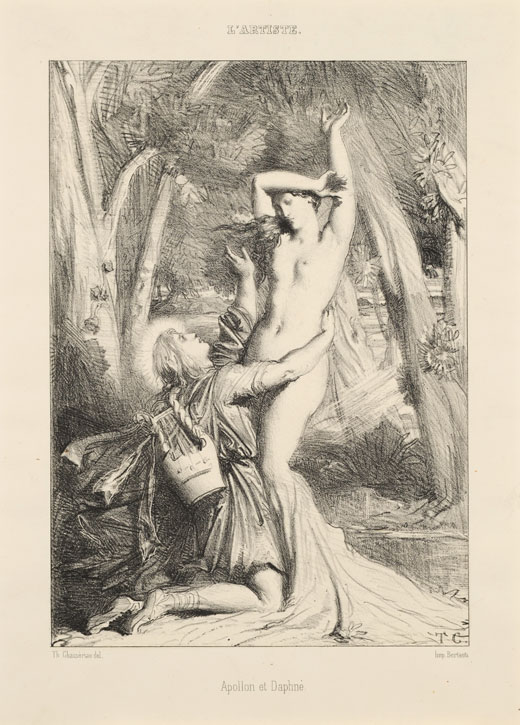

Apollo and Daphne

1558, etching on paper by Hieronymous Cock (c.1510–1570)

Take, for example, an etching of Apollo and Daphne made by Hieronymus Cock (c.1510–1570) in Antwerp in 1558. Here, the sun god pursues the terrified nymph in an attempt to rape her. She asks her father, the river god Peneus, for help and consequently turns into a laurel tree. In keeping with Ovid's descriptions, the artist has stressed the closeness of the pursuer to the pursued. The action is further intensified by showing Daphne in the process of metamorphosing while still in flight. However, there is a lack of empathy for the pursued; the artist again follows Ovid in the way he exposes her breasts to Apollo and, by extension, to the viewer – the vulnerability of the female body is opened up to the male gaze.

Apollo and Daphne

1844, lithograph on paper by Théodore Chassériau (1819–1856)

Next to this work in the display is the lithograph of Apollo and Daphne by Théodore Chassériau (1819–1856), made in Paris in 1844, almost 300 years after the etching by Hieronymus Cock. The unusual iconography of Apollo kneeling suggests his submission to Daphne as he pleads with her to reciprocate his love. Is this Chassériau's attempt to validate Apollo's intentions? The pose intensifies the emotional force of the episode and draws attention to Daphne's changing form. Apollo is clearly touching her; Ovid describes how the sun god feels her skin and kisses her, even as she metamorphosises. Chassériau eroticises these incriminating advances and portrays Daphne as an idealised and passive nude, common in Romantic art of the time. Her serene expression further complicates questions around consent, passion and sexual violence.

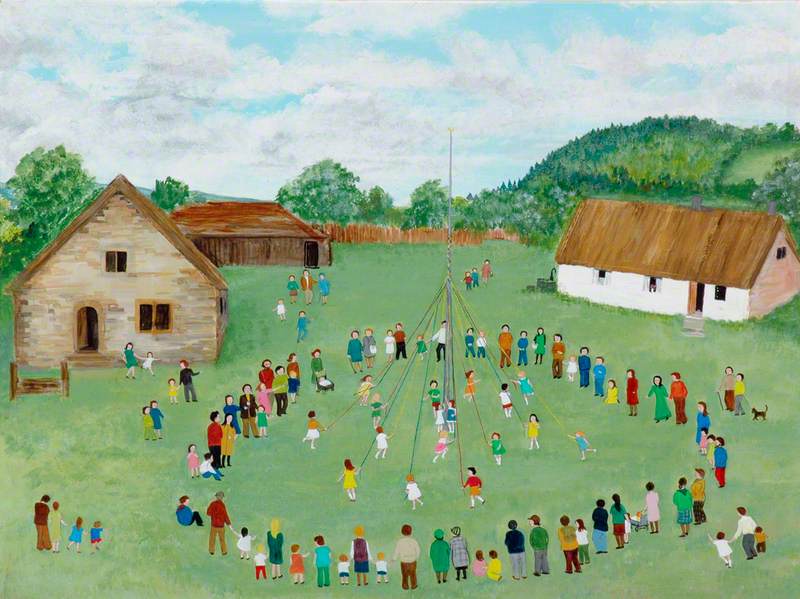

Two of the oldest works at The Barber, painted in tempera on wood, also explore the pursuit and metamorphosis of Daphne. They originally functioned as a pair of panels for the ends of a decorated chest known as a 'cassone'. Once thought to be by the anonymous 'Master of the Judgement of Paris' (active mid-fifteenth century), they are now regarded as having been painted in another unidentified Florentine workshop in the 1440s, but each panel by a different artist. This is not the only transformation they have experienced, as they have themselves metamorphosed in form and function from originally decorating a cassone to now hanging, as works of art in their own right, on the gallery walls.

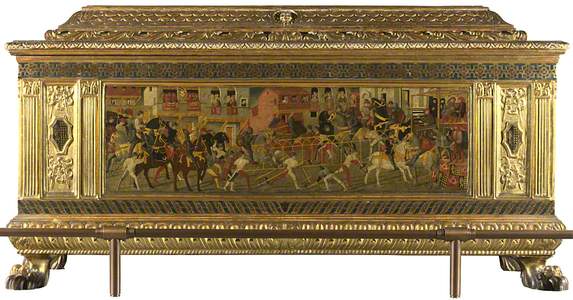

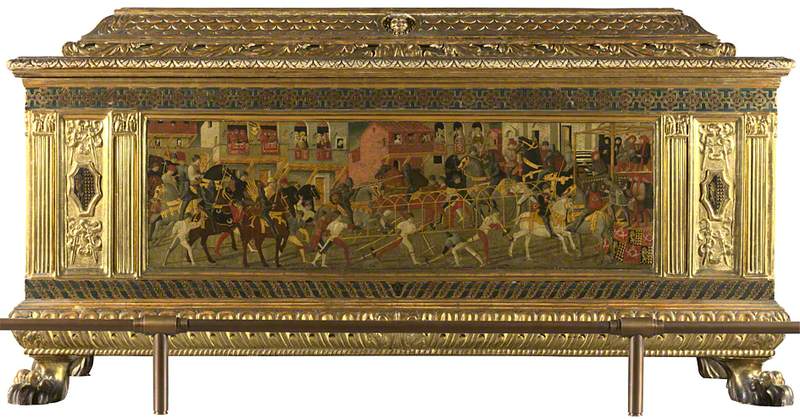

Cassone with a Tournament Scene

probably about 1455-65

Italian (Florentine) School

Examples of panels still intact on cassoni, now rare in British collections, can be seen on Art UK from collections such as The National Gallery. Others have been altered and retouched, mostly by nineteenth-century restorers, such as those now at the National Trust properties at Blickling, Knole and Cliveden.

Three Kings Drawn in Chariots in a Triumphal Procession

(cassone panel) mid-15th C

Italian (Florentine) School

Originally, such wooden chests were among the most expensive items in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Italian households and were usually made to celebrate marriages and show off the two newly united families' wealth. Initially, the bride's family commissioned them to transport her dowry and then store her clothes, fine textiles or wedding gifts. So they needed to be both decorative and practical, as well as demonstrating the patrons' intellect and status. Popular themes included illustrations of poetry, classical mythology and the Old Testament.

The specific mythological tale of the pursuit of Apollo and the flight of Daphne for The Barber's panels may seem an odd and inappropriate choice to us today. The import of rape in the mythological tale, which we now consider to be central, would have been almost invisible to Renaissance viewers.

However, it is still worth considering why this specific story was chosen for these decorative panels. Was it originally the popularity of the tale that mattered, and the reference to female virtue? Or did this panelled chest initially serve as a warning to the groom that he was to respect his new bride's wishes?

Such a state, or feeling, of ambiguity is prevalent in many of the myths in Ovid's Metamorphoses, particularly those decoratively illustrated on the sides of cassoni, and is partly why they have attracted so many artists since their creation and continue to inspire today. In particular, the ambiguity that surrounds the process of metamorphosing, the reasons for this shift-shaping and the reactions to this change by those around the evolving form raise powerful and provocative questions. Perhaps this, and the metamorphosis of the tales' meanings over time, encourages us to assess our own behaviour, who we are and who we want to be. This could not be more relevant or timely as our own world transforms into unknown shapes around us.

Helen Cobby, Assistant Curator at The Barber Institute of Fine Arts

To hear a short talk about The Barber's 'Changing Shapes' display, visit the gallery's Tuesday Talks Series Two page and scroll down