The Harland & Wolff Collection, held at National Museums Northern Ireland, comprises around 75,000 negatives – a selection of over 2,000 are shown on Art UK, hugely increasing the amount of photography on the website. These provide a remarkable visual record of the world-famous shipbuilding firm since the late nineteenth century.

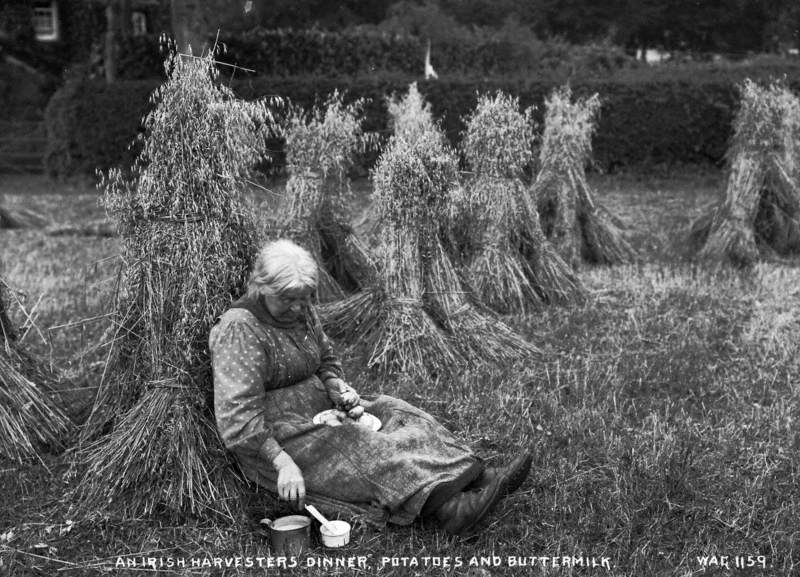

Harland & Wolff hired Robert John Welch to make documentary photographs of their work in Belfast's harbour. Welch was a prolific photographer and had spent many years using his glass plate camera to take pictures of Ireland's landscapes, people, ancient megaliths and monuments. His resulting work for Harland & Wolff not only gives us a view into Belfast's shipbuilding history, working methods and the famous ships the yard produced, but show Welch's talent for composition. With crisp clarity, he depicts on the giant, imposing scale of the ships' parts, the dramatic curves and lines of the vessels, and the almost alien industrial landscape of the shipyard.

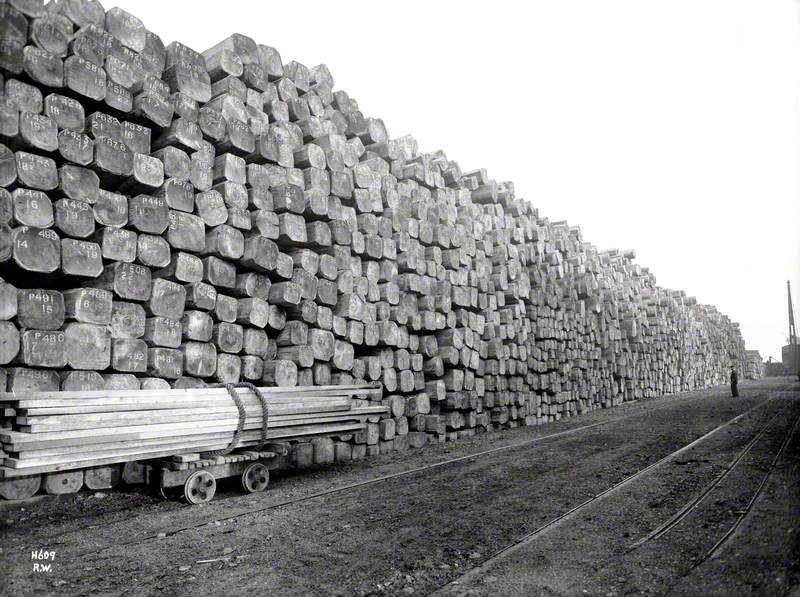

Log stacks, timber storage yard

c.1903

Robert John Welch (1859–1936) and Harland & Wolff (founded 1861)

With two giant cranes that dominate Belfast harbour's skyline, Harland & Wolff was once one of the largest shipbuilders in the world, making over 70 ships for the prominent White Star Line – most famously the RMS Titanic. Its workforce numbered around 35,000 in the 1930s, and the firm was also a key component of the war effort, despite the yards being damaged in the Blitz in 1941. The firm was still building boats as late as 2003.

Harland & Wolff hired Welch to be their official photographer from around 1894 up until 1920. His task was to capture the working life of the shipyard and document the build and launch of their boats.

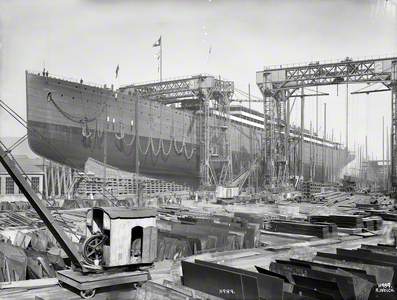

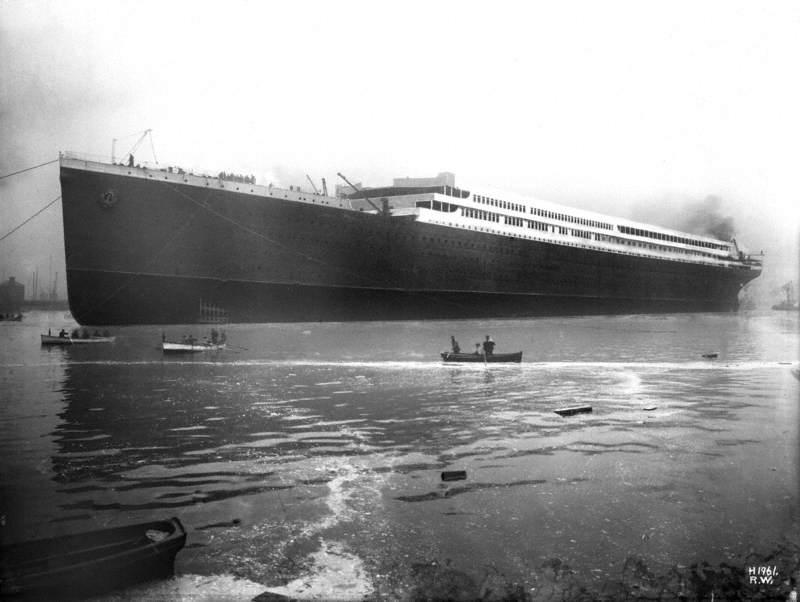

Vessel afloat after launch

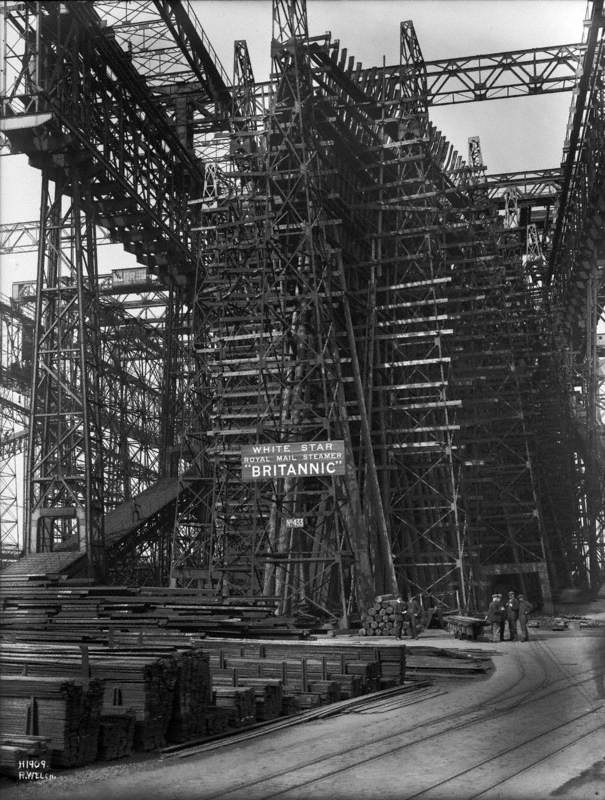

(Ship No. 433, 'Britannic') 1914

Robert John Welch (1859–1936) and Harland & Wolff (founded 1861)

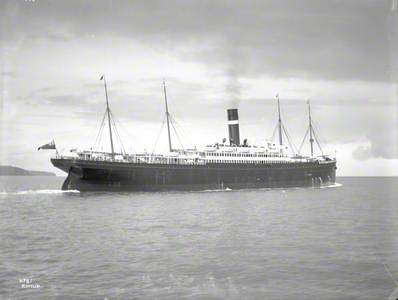

Notable examples of significant builds include SS Britannic – the largest ship to be lost in the First World War. Originally built as a passenger liner, the Britannic was requisitioned by the war effort and became a hospital ship. A naval mine sank the Britannic in 1916, near the Greek island of Kea. The shipwreck, explored by Jacques Cousteau in 1975, is one of the largest on the sea floor.

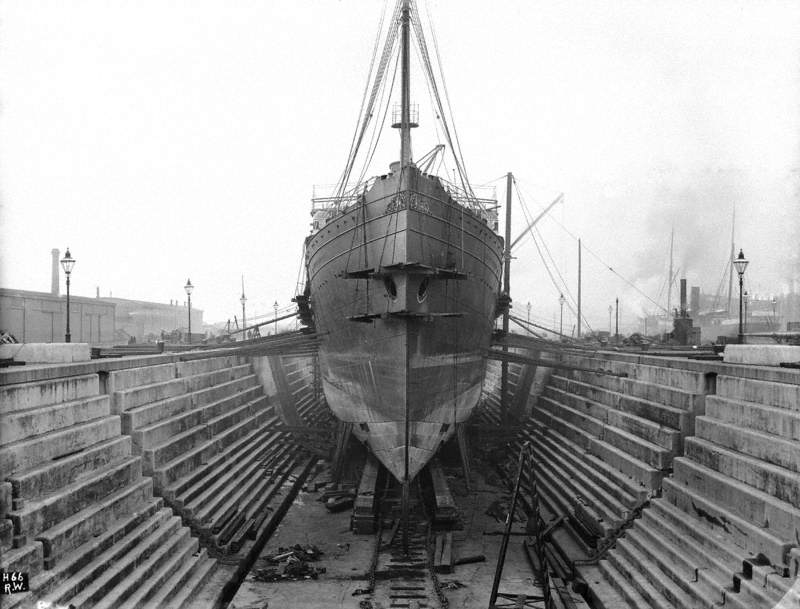

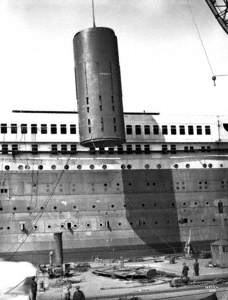

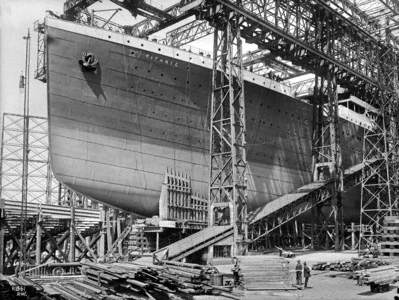

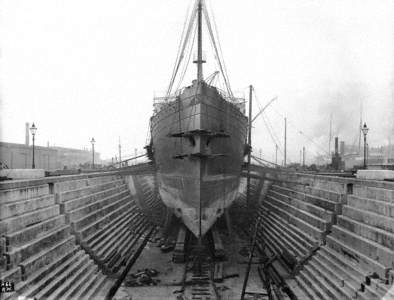

Port bow view on slip prior to launch

(Ship No. 401, 'Titanic') 1911

Robert John Welch (1859–1936) and Harland & Wolff (founded 1861)

Most people know the tragic history of the Titanic, a sister ship to the SS Britannic, as portrayed in James Cameron's blockbuster movie. The largest ocean liner at the time, the Titanic was built and launched in Belfast, but sunk on her maiden voyage in 1912 after hitting an iceberg. Over half the estimated 2,200 passengers died, making the event the deadliest peacetime sinking of a cruise ship to date.

The event was a blow to the pride of Northern Ireland's industry and a museum – Titanic Belfast – was only opened in 2012.

Another ship featured in the Harland & Wolff archive is the RMS Republic, a palatial liner known as the 'Millionaires' Ship': wealthy American passengers enjoyed taking cruises in the luxurious cabins and spaces of the vessel, and the westbound crossings also carried Italian immigrants to their new homes in the states.

Starboard stern 3/4 profile steaming out of Belfast Lough

(Ship No. 345, 'Columbus (Republic)') 1903

Robert John Welch (1859–1936) and Harland & Wolff (founded 1861)

In 1901, off Massachusetts, the Republic entered thick fog and collided with liner SS Florida. Six people were killed in the collision, though fortunately the 736 other people on board were rescued by other nearby boats: the Republic was equipped with a new Marconi wireless telegraph system and sent out a distress signal – it was the first marine rescue enabled by radio. It is rumoured that the wreck contains the equivalent of $1 billion sunken treasure…

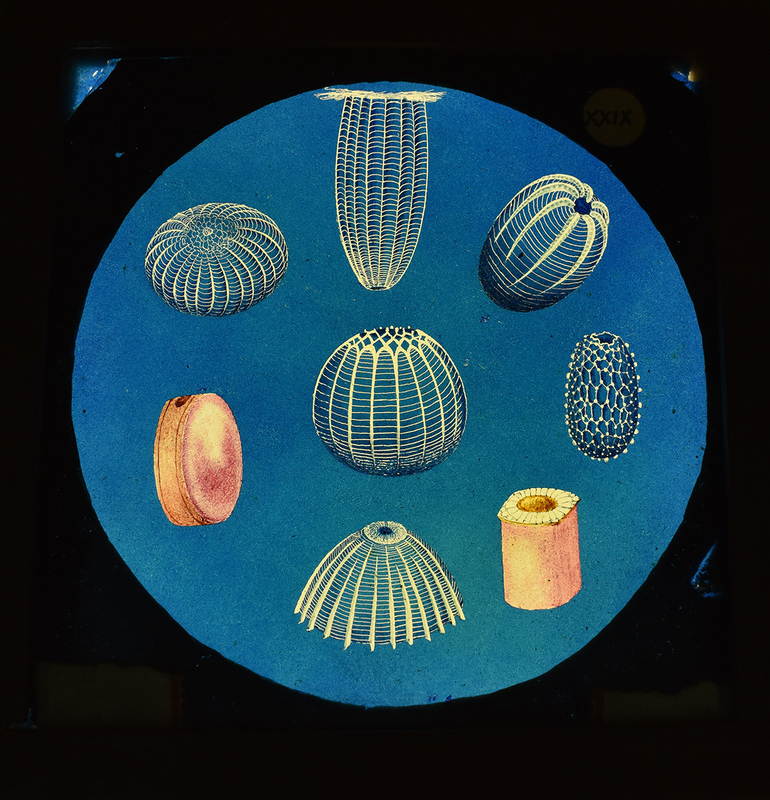

Robert John Welch was a vastly experienced early photographer: one of only ten photographers outside Britain to receive a royal warrant from Queen Victoria. Born in Strabane in 1858 (which is now located close to the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland), Welch inherited his love of cameras from his father, who operated as a professional photographer. When Welch's father died in 1875, the teenage Robert went to Belfast to train, establishing his own business by the 1880s. He spent his time photographing the people and streets of Belfast, but also loved the Irish landscape and natural history, being a member of the Royal Irish Academy as well as serving as president of the Belfast Naturalists' Field Club and the Conchological Society of Great Britain & Ireland (conchology is the study of mollusc shells).

The smooth curves of shells have a visual resonance in the more artistic products of his shipyard work: Harland & Wolff hired Welch as their chief photographer from the mid-1890s to the early 1920s, when the company established its permanent photographic department. Almost every glass plate made between 1894 and the First World War feature his initials. The process involved using a bulky camera to expose an image onto a piece of glass that had been basted in a light-sensitive emulsion of silver salts. Exposure times varied from a few seconds to a few minutes depending on the light available.

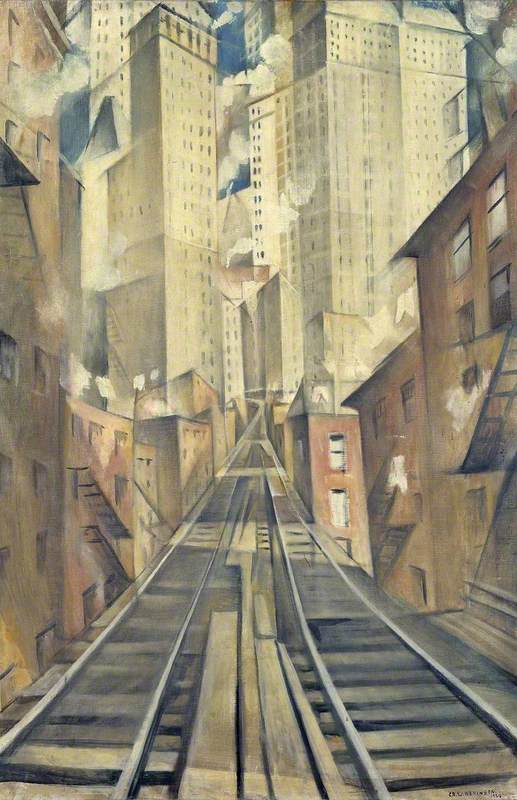

Often taken in difficult circumstances, Welch's photographs of the shipyard are prime examples of industrial photography: carefully selecting his viewpoints and using a great depth of field, Welch captures the achievements of the company and conveys the energy of the Second Industrial Revolution. The period saw rapid increases in manufacturing, and greater integration of machine tools in ordinary people's working lives – and artists were responding to this new way of life by including new industrial images in their work.

At the time Welch was working, Europe was about to see the birth of Futurism in Italy, Vorticism in Britain, and the development of the Russian avant-garde – artistic movements that captured the dynamism of the modern era.

Photography was fast developing as a new tool to capture the world in motion – photographers such as Arkady Shaikhet in Russia and Lewis Hine in America, for example, adopted an 'artistic' reportage style, showing people's lives integrated with new technology through unconventional compositions and bold uses of light and shadow: the silvery tones of early photographs are perfect for rendering the textures of iron and steel.

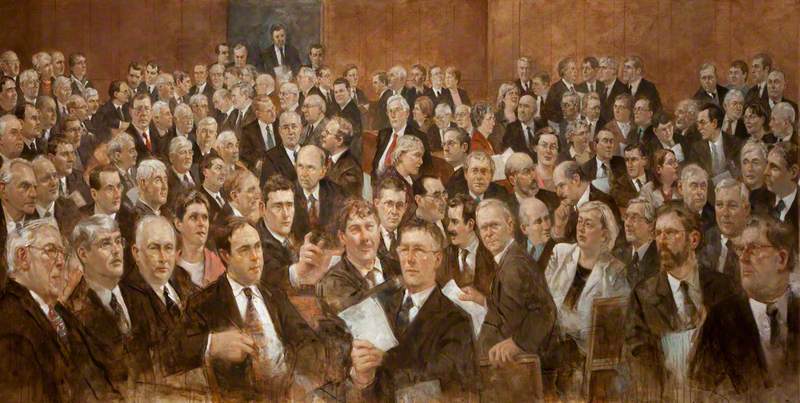

Shipyards – with their forceful, angular lines, smoke and debris, and people hard at labour – inspired many artists at the dawn of the twentieth century, including the painter John Lavery, commissioned to paint a mural homage to shipbuilding on the Clyde in Glasgow City Chambers.

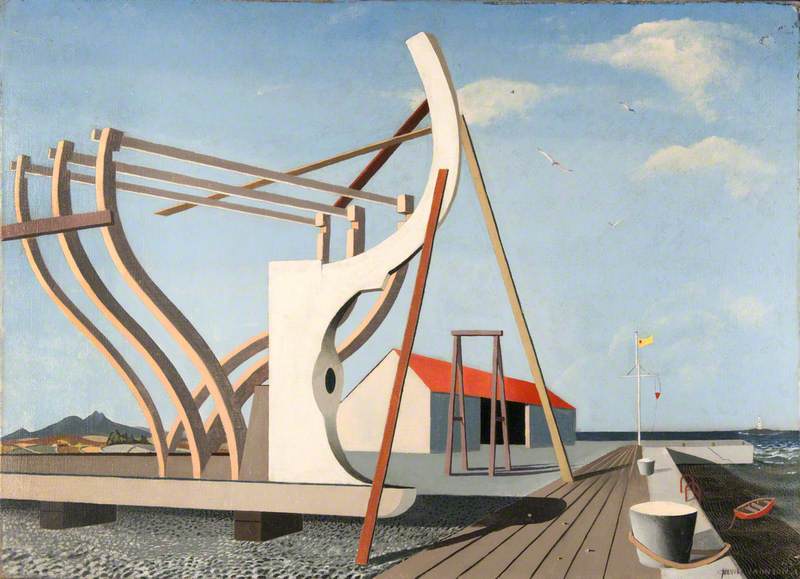

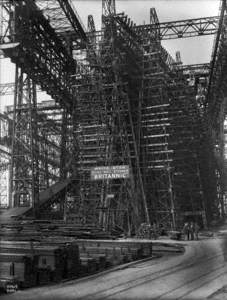

This painting at Ulster Museum by Gerald Burn echoes elements shown in Welch's photographs. The spikey timber frame obscuring the ship beneath is a peculiar sight – the carefully framed composition conveys an otherworldly view.

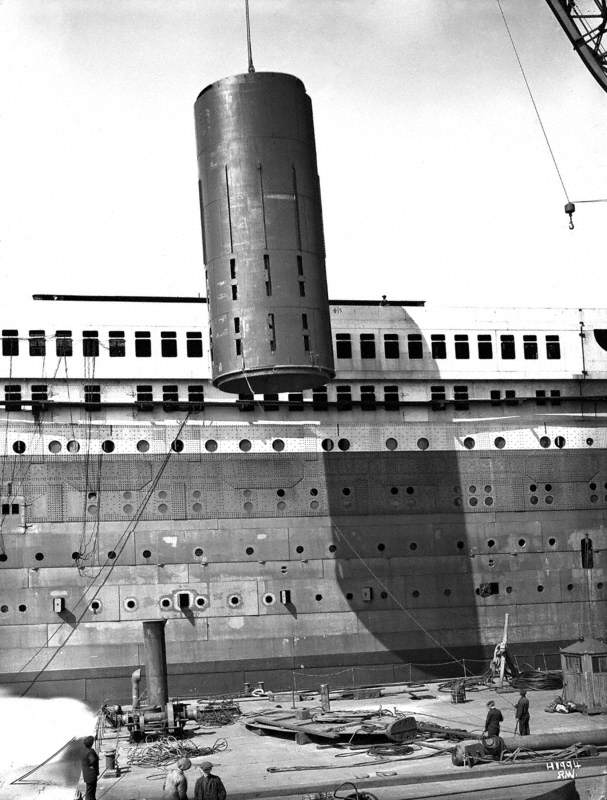

Bow view of vessel, framed

(Ship No. 433, 'Britannic') 1914

Robert John Welch (1859–1936) and Harland & Wolff (founded 1861)

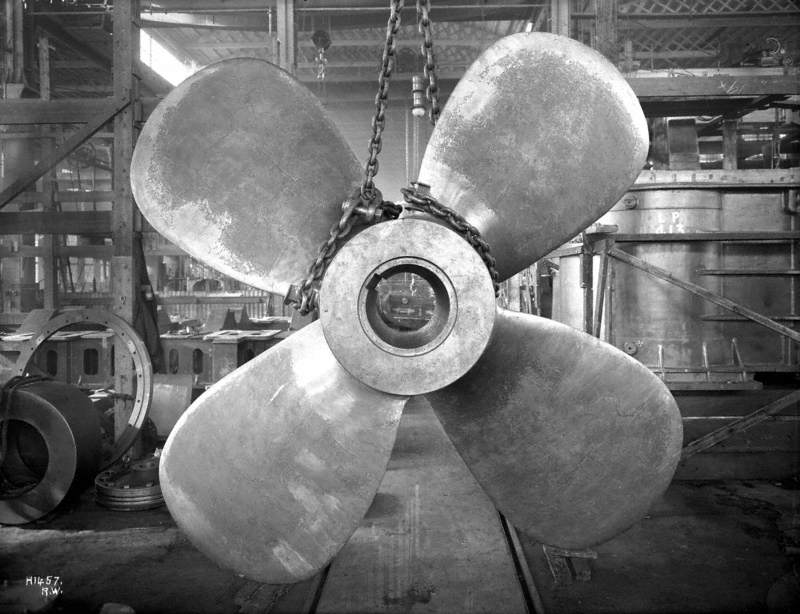

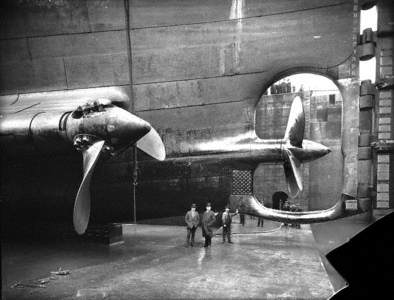

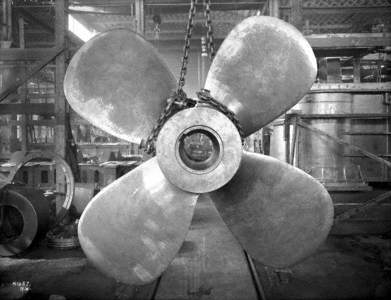

This focus on peculiar shapes and compositions is similarly found in many other of Welch's images: the imposing curves of a ship's hull, the dynamic thrust of a bow, and behemoth funnels suspended momentarily in the air.

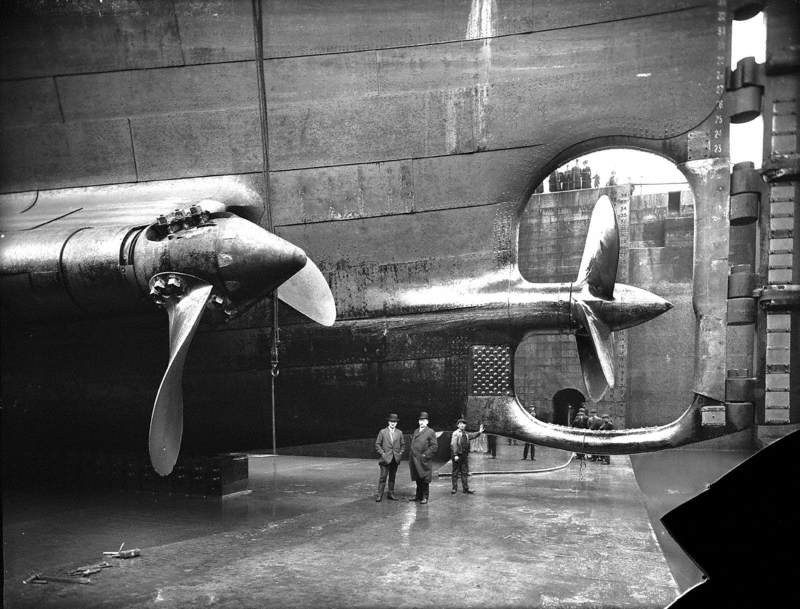

Starboard propeller bossing from floor of dry dock

(Ship No. 400, 'Olympic') 1911

Robert John Welch (1859–1936) and Harland & Wolff (founded 1861)

Robert Welch clearly revelled in the shapes made at the shipyard, choosing to focus his lens on the point where form and function meet.

HMS 'Hawke' collision damage – wooden patch at stern covering damage

(Ship No. 400, 'Olympic') 1911

Robert John Welch (1859–1936) and Harland & Wolff (founded 1861)

The clarity of the photographs allows us a clear view into the past, capturing moments of people at work over a century ago. The archive has a straightforward historical value: showing the techniques used by shipbuilders, how these huge structures were lifted clear out the water and patched up.

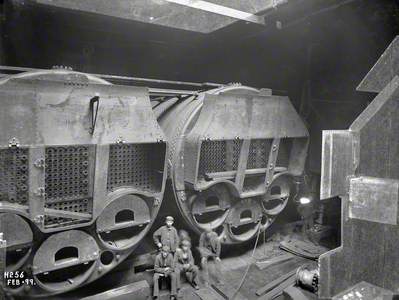

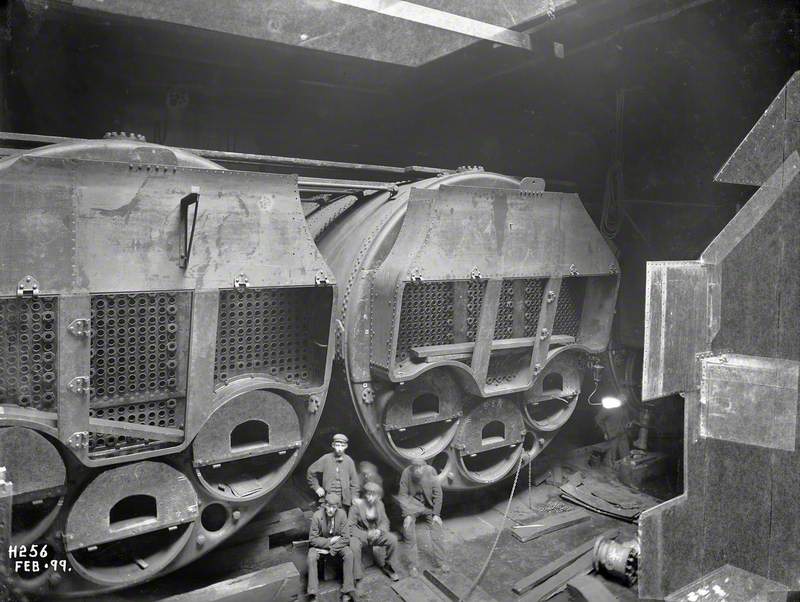

Installation of boilers in stokehold with posed workers

(Ship No. 317, 'Oceanic') 1899

Robert John Welch (1859–1936) and Harland & Wolff (founded 1861)

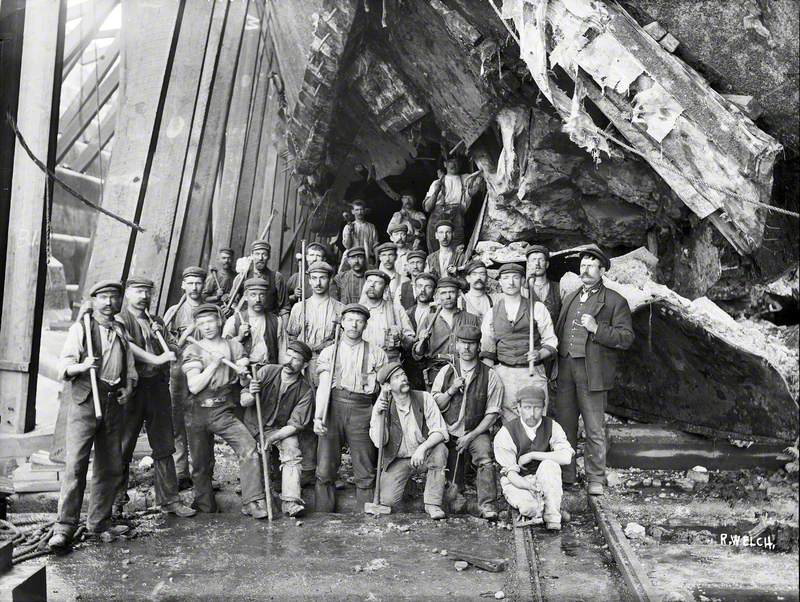

Occasionally, Welch includes people: workers taking a moment to pose next to their work (the photographic process would require stillness to get a clear image). Sometimes people are provided in the shot for a sense of scale.

The 'Black Squad' posed beneath the damaged section of hull

(Ship No. 299, 'China') 1898

Robert John Welch (1859–1936) and Harland & Wolff (founded 1861)

Here the boilermakers, or 'Black Squad', are shown – a type of worker new to the industry, who manipulated steel and iron to make and repair large boilers, essential for ships.

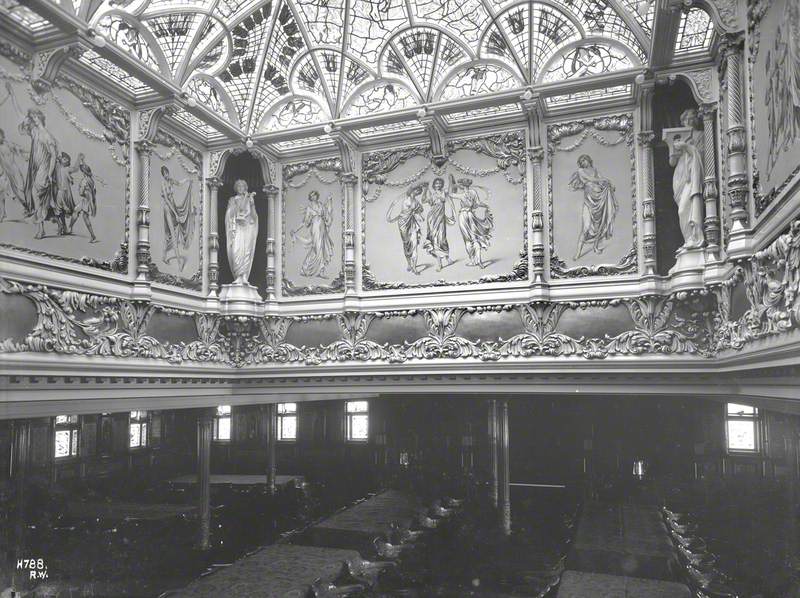

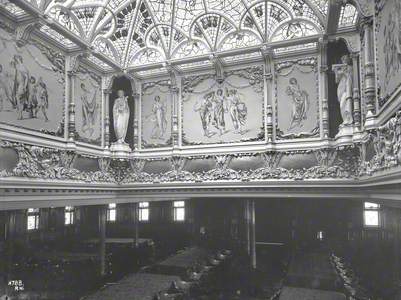

The photographs of the completed ship interiors also offer an insight into the social class structure of the time.

Third class six berth cabin

(Ship No. 390, 'Rotterdam') 1908

Robert John Welch (1859–1936) and Harland & Wolff (founded 1861)

Third class smoke room

(Ship No. 392, 'Pericles') 1908

Robert John Welch (1859–1936) and Harland & Wolff (founded 1861)

While travelling first class is still a concept familiar to us, the living furnishings of the ships are almost comedic in their disparity – compare the crowded six-berth cabin offered in third class accommodation to the chintzy frills of a first-class private sitting room or grandeur of a wooden staircase with intricately carved bannisters.

With hindsight, the Harland & Wolff archive can feel ghostly. Devoid of colour, these images hint at the temporariness of human endeavour – particularly the lavish, grand interiors of a ship we now know to be disintegrating on the ocean floor.

First class suite bedroom B59

(Ship No. 401, 'Titanic') 1911

Robert John Welch (1859–1936) and Harland & Wolff (founded 1861)

While Harland & Wolff continues to adapt to changes in global industry, now working on much smaller projects, Belfast retains vestiges of its huge shipbuilding history through its harbour and also through archives such as that at National Museums Northern Ireland. The scale of the early twentieth century's ambitious engineering projects would be hard to imagine if it were not for documentary images. The Harland & Wolff archive is a unique window into history – appreciated not only for when it can show us about the era, but also as a set of beautiful images with aesthetic value, enabled by Welch's talent as an artist.

Jade King, Lead Editor at Art UK

Launch party on platform and bottle breaking on port bow

(Ship No. 410, 'Edinburgh Castle') 1910

Robert John Welch (1859–1936) and Harland & Wolff (founded 1861)

If you are interested in exploring the rest of the Harland & Wolff archive, please contact National Museums Northern Ireland directly at picture.library@nmni.com