Canterbury Museums and Galleries’ art collection is freely available to the public at ART UK. The online collection database allows you to experience many well-known, and some overlooked, paintings from their collection from the comfort of your own home.

This timeline of 6 oil paintings from the collection spans from the 16th century to the 20th century and showcases the different areas of Canterbury which were of particular interest to artists – not only aspects of the city, like the Cathedral, which were represented repeatedly, but also how these different parts of Canterbury were selected, perceived, and depicted so diversely by artists through time – highlighting the history and unique beauty of the city and its evolution.

17th Century

.

Interior of Canterbury Cathedral, Kent, the Quire

This oil painting by an unknown artist of the interior of Canterbury Cathedral shows the Quire as it appeared in 1663. Due to the artists’ attention to detail when representing the architecture, it is evident that the Cathedral’s interior has barely changed since the 17th century. The painting captures the sense of depth and scale of the building, the stone vault is 18 metres or 59 feet high. The inclusion of the diminutive figures in the centre highlights the heights of the vaulted ceilings. The detailed ornamentation and gothic arches create a realistic sense of the space. The artist also chose to offer a perspective that many would never be able to experience in real life, as the viewer experiences the scene suspended in mid-air.

unknown artist

Oil on canvas

H 77 x W 64.5 cm

Canterbury Museums and Galleries

The Cathedral’s Quire is the area that provides seating for the clergy and church choir, it is used regularly to this day and is now over 800 years old. It was rebuilt after a disastrous fire in 1174 and is thought to be the first Gothic building in the UK. The fire started when embers from a cottage fire landed unnoticed on the Cathedral roof. The fire burnt so intensely it melted the lead roof and burnt the interior of the building. It took ten years and two architects to rebuild the Cathedral, the change from the original Norman style is evident through the Nave to the newer Quire.

18th Century

.

Old Ridingate, Canterbury, as in 1770

This oil painting depicts a part of Canterbury that no longer exists, unlike the other paintings in this collection which feature landmarks which have remained relatively unchanged since they were painted. The Ridingate, previously called Radingate, or Rider’s Gate, was on the Roman military road that connected Dover and Canterbury (the modern day A2). The gate which was between Watling Street and Old Dover Road was taken down in 1782, and in 1791 it was replaced by a gothic brick arch. H. W. Hayman painted this scene over 100 years after this structure existed, subsequently one can assume that it was painted using much earlier sketches of the original gate and not from life.

H. W. Hayman

Oil on canvas

H 31 x W 40.5 cm

Canterbury Museums and Galleries

The Ridingate was one of six gates that surrounded the city. None of these structures survived to the present day and the view now is quite different to the one provided in this painting. The painting and the interest in this lost landmark are emblematic of the deep history of Canterbury. The public interest in the city's history results in the production of artworks such as this, artworks that also act as visual documents of an evolving city over hundreds of years.

19th Century

.

Canterbury, Kent, from the Stour Meadows

Alfred Stannard was an English landscape artist. This painting Canterbury, Kent, from the Stour Meadows observes Canterbury from afar, from the banks of the River Stour. This view and style of scene was very popular in paintings of the 19th and early 20th century. The Romantic influence of John Constable is apparent in the expressive and somewhat ominous sky. Despite the initial focus on the natural landscape with large expressive twisting trees with the cows and figures in the foreground, one is pulled towards the background, to the distinctly man-made objects of Canterbury Cathedral and the Westgate as they stand out against the horizon.

Alfred Stannard (1806–1889)

Oil on canvas

H 45.5 x W 65.5 cm

Canterbury Museums and Galleries

The Cathedral appears to be the main focus of interest as it is placed in direct eye-line, framed by the trees and surrounding landscape and illuminated by the cluster of clouds behind. Despite its size, Stannard depicted the minute architectural details of the famous building including the Gothic arches and turrets which are stark against the softer forms of the sky. The rest of the city surrounding it is dwarfed and the atmosphere of the painting blends into one of tranquillity and stillness.

Canterbury from Kingsmead, Kent

This oil painting of Canterbury Cathedral from across the River Kingsmead is by British landscape painter, wood-engraver, and etch, Alfred Dawson. The scene is barely lit by sunlight and the muted pastel colour palette makes the painting feel still and timeless. The imposing silhouette of the Cathedral contrasts the colour-tinged clouds with the faint ghost of the Cathedral windows illuminating it from within. Unlike Stannard’s, Dawson’s painting is a more Romantic depiction of the Cathedral, with a focus on light and atmosphere. There is a dream-like quality to the hazy Cathedral emerging from the sunlight, as if a Gothic castle, standing alone surrounded by nature. The reflection of light in the river adds to this otherworldly atmosphere.

Alfred Dawson (1843–1931)

Oil on panel

H 20.4 x W 25.4 cm

Canterbury Museums and Galleries

Dawson produced multiple paintings of Canterbury, often with the Cathedral as a focal point or feature. Dawson’s oeuvre includes hazy pastoral scenes with historic buildings often bathed in light and soft colours. He also frequently included bodies of water and emphasised the way light reflected off its surface.

20th Century

.

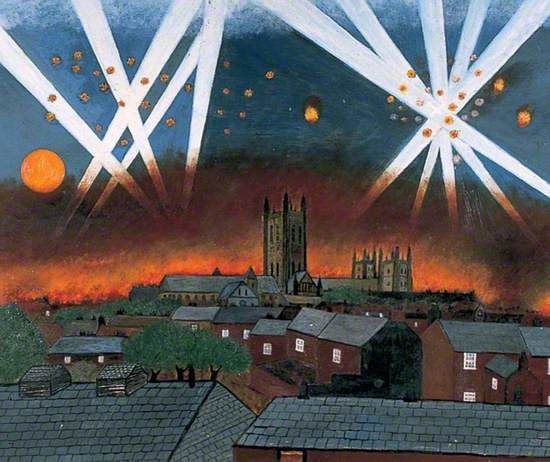

Canterbury Blitz, 1 June 1942

The Baedeker Blitz was a series of attacks by the Luftwaffe on English cities during World War II. It was named after a series of German tourist books called Baedekers, which included detailed maps of sites of interest or historical significance in Britain. The Germans used this guide to find targets for a series of revenge bombings which focused on locations of cultural significance rather than military value. In June 1942, businesses, homes and schools were destroyed as chandelier flares were dropped to light up the whole city and incendiaries showered on the Cathedral. Miraculously, it was saved from the fire raging through the city due to a small group of fire watchers on the roof who would pick up and extinguish the incendiary bombs.

A. E. Hallady

Oil on board

H 50.5 x W 61 cm

Canterbury Museums and Galleries

Despite the survival of the Cathedral, the destruction of Canterbury was still painfully apparent as many buildings, sites and lives were lost. But this painting showcases a specific notable day in Canterbury’s history and despite the death and destruction, the Cathedral still stood strong amongst it all – a constant beacon of hope and faith amid the damaged city.

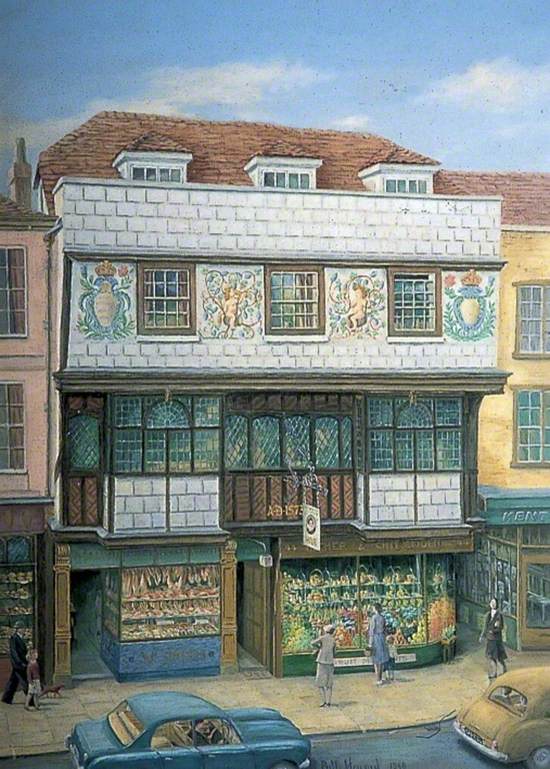

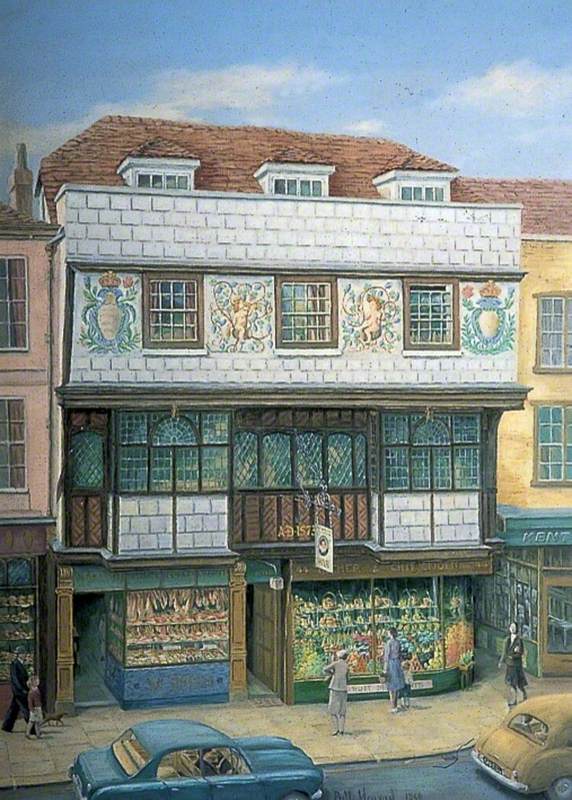

Tudor Tea Rooms, High Street, Canterbury, Kent

This highly detailed oil painting depicts a particularly memorable building in Canterbury, Number 44-45 High Street – which is now Caffe Nero, as it would have appeared in the 1960’s. It is referred to as Queen Elizabeth’s Guest Chamber and is now a Grade II listed building. The site was established in 1200 and was occupied by the Crown Inn from the 15th to 18th centuries.

In 1899, the first floor was separated from the ground floor shops, which allowed the development of the first floor into a single large room, which has been known since 1904 as “Queen Elizabeth’s Guest Chamber” – a probable reference to the three days Queen Elizabeth 1st is said to have spent there for her 40th birthday in 1573.

Bill Howard (d.c.1975)

Oil on board

H 58.7 x W 43.3 cm

Canterbury Museums and Galleries

Buildings like these are emblematic of the character of Canterbury, where history and stories are embedded in the sites that are seen and experienced on an everyday basis. Despite the building being extremely visible to a passer-by, paintings like this help to highlight the historic beauty of a building that can often be somewhat overlooked on the (normally) busy high street.

This Curation was researched and written by Emma Williams, a Collections Volunteer at The Beaney.