Bright Shadows: Scottish Art in the 1920s is a temporary exhibition at the City Art Centre in Edinburgh. Marking one hundred years since the dawn of the ‘Roaring Twenties’, the exhibition showcases a selection of paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures from the City Art Centre’s collection of Scottish art. Featured artists include J.D. Fergusson, S.J Peploe, Eric Robertson, Dorothy Johnstone, Stanley Cursiter and William McCance. This Curation presents some of the highlights of the exhibition.

Introduction

The 1920s is a period associated with Art Deco design, jazz music and flapper dresses. Yet this is only one side of the story. It was a decade of contrasts: high spirits interwoven with sombre contemplation, and grand aspirations tempered by hard realities. Some people reflected on the recent losses of the First World War, while others looked forward to an era of new possibilities. In an age of social, political and economic change, Scottish artists responded in a variety of ways.

1920

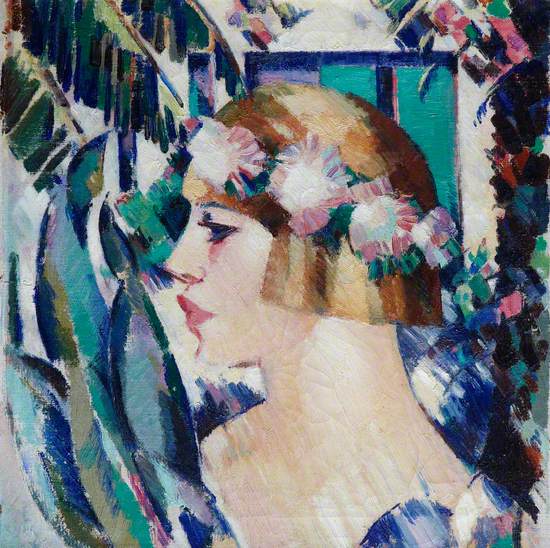

Villa Gotte Garden

The Scottish Colourists painted regularly in the south of France during the 1920s. John Duncan Fergusson stayed in the area with his partner Margaret Morris, who organised avant-garde dance schools every summer. Classes were held in the grounds of a château near Antibes, and Fergusson found plentiful inspiration among the dancers in this Mediterranean setting.

Villa Gotte Garden captures the dazzling light and colour of the Cap d’Antibes, but the painting also conveys the spirit of the times. The model appears in profile, accentuating the angular geometry of her fashionable bobbed haircut. Posing with perfect stillness among the foliage, and wearing a headdress of garlanded flowers, she exudes an air of youthful confidence.

John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961)

Oil on canvas

H 37.5 x W 37.1 cm

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

Portrait of an Artist, William Skeoch Cumming (1864–1929)

James Pittendrigh MacGillivray was a painter, poet and musician, though he is chiefly known as a sculptor. Originally from Aberdeenshire, he moved to Glasgow in 1876, where he became associated with the Glasgow Boys.

This bronze bust dates from 1920, when MacGillivray’s career and reputation were firmly established. The subject is the painter and designer William Skeoch Cumming, a friend who shared MacGillivray’s interest in Scottish history and culture.

MacGillivray was a Scottish nationalist and supporter of home rule. An early proponent of the ‘Scottish Renaissance’, his poems were often written in Scots dialect. In 1922 he published a volume of verse entitled Bog-Myrtle and Peat Reek.

James Pittendrigh MacGillivray (1856–1938)

Bronze

H 76.8 x W 52.7 x D 43.1 cm

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

Cecile Walton at Crianlarich

Eric Robertson attended Edinburgh College of Art prior to the First World War. He was a founding member of the Edinburgh Group, an exhibiting collective that attracted notoriety for pushing moral and aesthetic boundaries. As one critic wrote in 1920, visitors to their exhibitions expected ‘something of pagan brazenness rather than parlour propriety’.

This portrait depicts the artist Cecile Walton, whom Robertson had married in 1914. It was painted in spring 1920 following a holiday to Crianlarich in the Highlands. The couple rented a cottage near a series of waterfalls, and visitors were encouraged to bathe nude.

Both Robertson and Walton were promising talents, but their careers faltered after the failure of their marriage in 1923.

Eric Harald Macbeth Robertson (1887–1941)

Oil on canvas

H 91 x W 105 cm

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

1921

Lily

Benno Schotz was born in Estonia, and originally moved to Glasgow in 1912 to study engineering. However, after attending evening classes at Glasgow School of Art, where he received encouragement from Fra Newbery, he decided to retrain as a sculptor.

This expressive bronze head is an early work by Schotz, produced two years before he became a full-time sculptor in 1923. Throughout the 1920s he made a range of head studies, including portraits of well-known art world personalities such as the artists James Pittendrigh MacGillivray and James McBey, and the art dealer Alexander Reid. The identity of this sitter remains something of a mystery though; the piece is simply entitled Lily.

Benno Schotz (1891–1984)

Bronze

H 27.7 x W 23.5 x D 31.2 cm

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

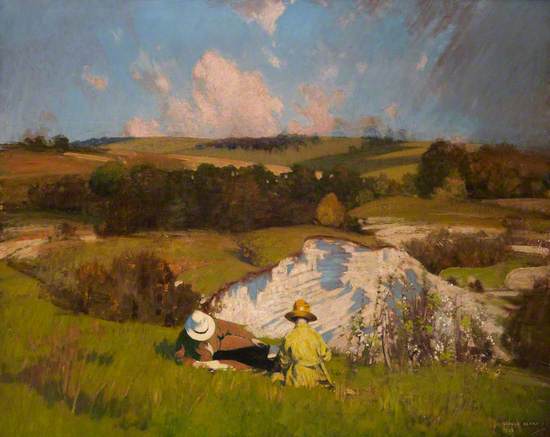

The Chalk Pit

This painting portrays an idyllic vision of rural leisure-time in 1920s Britain. A pair of figures recline on a grassy bank among the rolling hills of the South Downs in Sussex. Improved transport and greater opportunities for recreation meant that countryside pursuits such as walking, cycling and camping became increasingly popular in the interwar years.

The Ayrshire-born artist George Henry executed several pictures on this theme during the 1920s and 1930s. Henry had made a name for himself decades earlier, as a daring member of the Glasgow Boys who blended French Realism with Celtic and Japanese influences. By the early 20th century, however, he had settled in London, and was more concerned with society portraits and scenic landscapes.

George Henry (1858–1943)

Oil on canvas

H 106.7 x W 127.1 cm

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

1923

A Glass of Milk

Stanley Cursiter developed his mature painting style during the 1920s. Before the First World War he had experimented with Italian Futurism, and collaborated with Clive Bell and Roger Fry to bring avant-garde art exhibitions to Edinburgh. After his demobilisation in 1919, he focused on more conventional subject-matter and adopted a refined, naturalistic approach.

A Glass of Milk exemplifies this new direction, with its muted colour palette and mood of restraint. In the coming years Cursiter became well known for his elegant still life arrangements and fashionable portraits.

The 1920s also saw him establish a parallel career in gallery administration. Between 1925 and 1930 he served as Keeper of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

Stanley Cursiter (1887–1976)

Oil on canvas

H 40.6 x W 45.7 cm

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

Rest Time in the Life Class

Dorothy Johnstone was just 16 when she enrolled at Edinburgh College of Art. Having excelled as a student, she joined the college’s teaching staff in 1914.

This painting offers a glimpse into one of Johnstone’s classes. A life model is shown taking a break from posing, while students discuss and refine their compositions. Johnstone herself appears in the top right corner, working at an easel.

Rest Time in the Life Class was displayed in 1924, the same year that Johnstone married the artist D.M. Sutherland. She was subsequently obliged to resign from her teaching position, as married women were barred from holding full-time posts. Although opportunities for women artists slowly improved during the 1920s, discrimination remained common.

Dorothy Johnstone (1892–1980)

Oil on canvas

H 121.5 x W 106.2 cm

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

1924

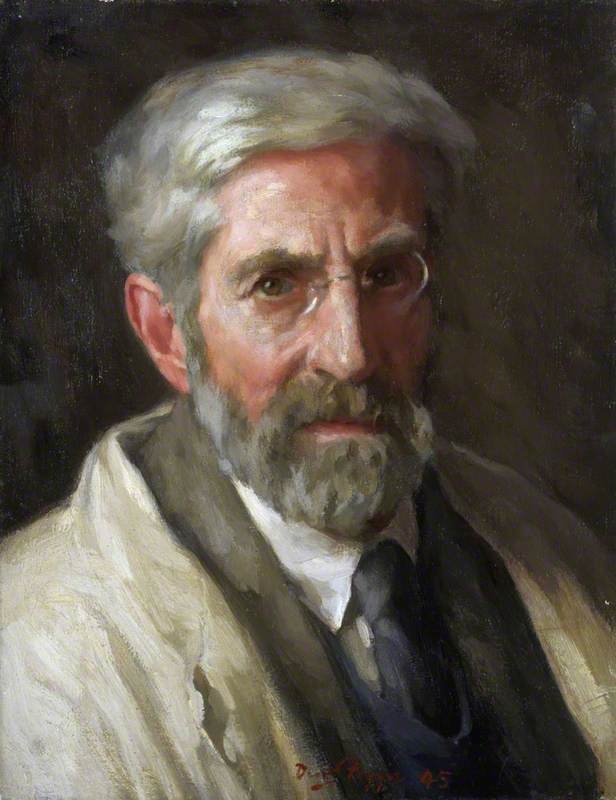

James Pryde (1866–1941)

Portraiture flourished in Britain during the 1920s and 1930s, providing artists with an important source of income. Glasgow-born artist (Herbert) James Gunn started his career as a landscape painter, but focused increasingly on portraiture as he matured.

This early portrait by Gunn depicts the senior Scottish artist and designer James Pryde. The two men shared a studio in London in the 1920s, and Gunn painted Pryde on multiple occasions.

Having settled permanently in London, Gunn established himself as a successful society portraitist. He counted aristocracy, politicians and businessmen among his clients, and was commissioned to produce the coronation state portrait of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.

Herbert James Gunn (1893–1964)

Oil on canvas

H 127.7 x W 102 cm

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

National Gallery and Castle, Edinburgh

The Scottish National War Memorial was the most significant public art project to take place in Scotland in the 1920s. Designed by the architect Robert Lorimer, and located within the precincts of Edinburgh Castle, the Memorial was devised to honour the causalities of the First World War on a national scale. Construction work began in 1923 and continued until 1927.

This etching by Nicol Laidlaw records the progress of the project in 1925. A series of cranes and temporary structures can be seen on the horizon, gradually transforming Edinburgh’s architectural skyline.

The revival of printmaking was a major trend in Scottish art during the 1920s. Increasing numbers of artists earned a living making etchings for a buoyant commercial market.

Nicol Laidlaw (1886–1929)

Etching on paper

H 22.5 x W 30 cm

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

A Garment of War

The First World War had a profound effect on many Scottish artists. Although D.Y. Cameron was too old to enlist, he accompanied the Canadian Expeditionary Force as an official war artist.

He spent the autumn of 1917 with troops at Passchendaele and the Vimy-Lens front, sketching under constant threat of shelling and sniper fire. In January 1919 he returned to work near Ypres, gathering material for both Canadian and British government commissions.

For several years Cameron was occupied almost exclusively with battlefield landscapes. A Garment of War was the final large canvas in this series, produced in the mid-1920s. The scene of shattered buildings silhouetted against a blazing sky is a potent reminder of the devastation of war.

David Young Cameron (1865–1945)

Oil on canvas

H 121.9 x W 167 cm

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

St Andrew Square – The Banks

Ernest Lumsden was one of the leading lights of the 20th century printmaking revival in Scotland. In 1925 he published The Art of Etching, an influential handbook that traced the history of intaglio printing as well as providing practical guidance on techniques.

Lumsden’s abilities as an etcher were underpinned by his skills as a draughtsman. This pencil drawing of St Andrew Square in Edinburgh records the architecture of the city’s banks with exceptional precision.

Following the Wall Street Crash in October 1929, the international market for printmaking virtually collapsed. Although Lumsden continued to champion etching, he was forced to diversify his practice to guarantee an income and began taking commissions as a portrait painter.

Ernest Stephen Lumsden (1883–1948)

Pencil on paper

H 26.5 x W 36 cm

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

Sanctuary

William Johnstone was among the generation of artists who benefited most from greater freedom to travel in the 1920s. In 1925 the young graduate received a Carnegie Travelling Scholarship from the Royal Scottish Academy. He relocated from Edinburgh to Paris and began training under the Cubist painter André Lhote. He absorbed both Cubist and Surrealist influences, and became interested in the possibilities of abstraction.

Sanctuary was probably developed over a number of years during this period. The initial composition is thought to date from Johnstone’s student days in Edinburgh, but major revisions seem to have been made following his experiences abroad, reflecting his changing outlook.

William Johnstone (1897–1981)

Oil on board

H 122.5 x W 121.9 cm

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

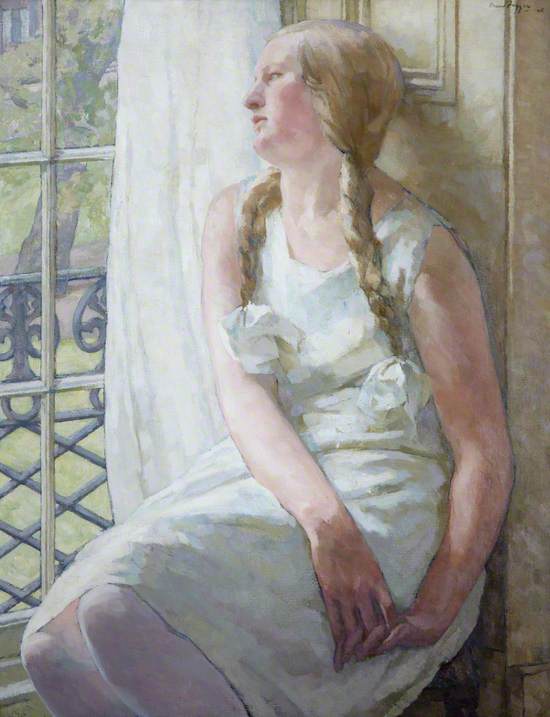

Dreams

The First World War created an uncertain economic climate for artists. Prior to the conflict, collectors and dealerships sustained many careers through sales of works. However, patronage and commercial support dwindled in later years, leading artists to seek additional forms of income. Teaching, at least on a part-time basis, became increasingly common.

Dundee-born artist David Foggie started teaching at Edinburgh College of Art in 1919. He spent the 1920s on a distinguished body of staff that included Henry Lintott, Adam Bruce Thomson, D.M. Sutherland and Dorothy Johnstone.

As a tutor, Foggie placed great emphasis on composition, tonal relations and accurate drawing skills. Dreams demonstrates his own accomplishments in these areas.

David Simpson Foggie (1878–1948)

Oil on canvas

H 92 x W 71.4 cm

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

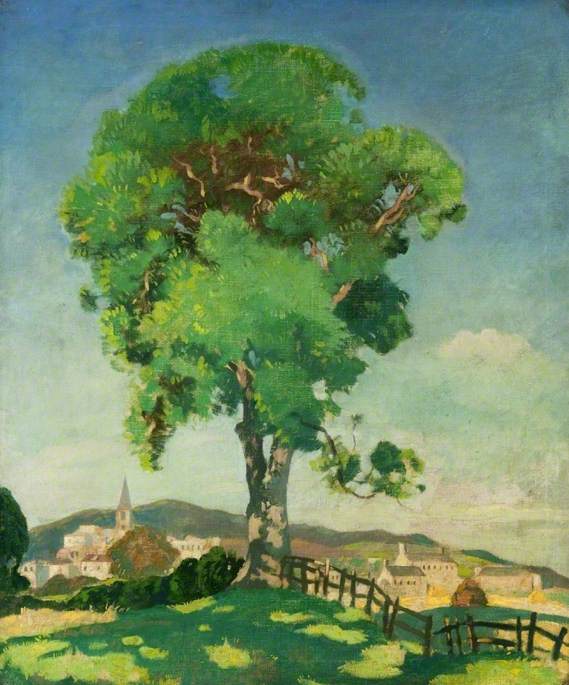

View from the Mound, Edinburgh, Looking West

In the early 1920s young artists were often frustrated by the lack of opportunities to display their work. Established exhibiting organisations like the Royal Scottish Academy tended towards traditional conventions, so artists with more modernist tastes had to look elsewhere. The 1922 Group was among the new societies that emerged to fill the gap.

The 1922 Group was so called because most of its original members had graduated from Edinburgh College of Art in 1922. William Crozier was a founding member, along with William Gillies and William MacTaggart. Like many of his peers, Crozier trained in Paris in the 1920s and experimented with Cubism. Unfortunately, his career was cut short in 1930, when he died after an accident in his studio.

William Crozier (1893–1930)

Oil on panel

H 55.2 x W 46.3 cm

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

Portrait with Still Life

Design trends of the 1920s typically broke with tradition and embraced modernity. Women’s fashions underwent a particularly overt transformation during this period, with loose-fitting, drop waist dresses and bobbed haircuts replacing more conventional Edwardian styles. This portrait of an unidentified young woman illustrates the confident style of the era.

George Telfer Bear was born in Greenock and studied at Glasgow School of Art. Having spent some years in Canada, he returned to Scotland in the early 1920s. Bear’s paintings feature bright colours and bold outlines, revealing an affinity with the Scottish Colourists. Indeed, he exhibited alongside Peploe, Cadell and Hunter at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris in 1931.

George Telfer Bear (1876–1973)

Oil on board

H 100.3 x W 74.2 cm

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

Explore artists in this Curation

View all 15-

Eric Harald Macbeth Robertson (1887–1941)

Eric Harald Macbeth Robertson (1887–1941) -

James Pittendrigh MacGillivray (1856–1938)

James Pittendrigh MacGillivray (1856–1938) -

Ernest Stephen Lumsden (1883–1948)

Ernest Stephen Lumsden (1883–1948) -

William Crozier (1893–1930)

William Crozier (1893–1930) -

William Johnstone (1897–1981)

William Johnstone (1897–1981) -

Nicol Laidlaw (1886–1929)

Nicol Laidlaw (1886–1929) -

Herbert James Gunn (1893–1964)

Herbert James Gunn (1893–1964) -

David Young Cameron (1865–1945)

David Young Cameron (1865–1945) -

Stanley Cursiter (1887–1976)

Stanley Cursiter (1887–1976) -

David Simpson Foggie (1878–1948)

David Simpson Foggie (1878–1948) - View all 15