In 1961 the American-born painter Alfred Cohen (1920–2001) staged his most ambitious London exhibition, 'Aspects of the Thames'.

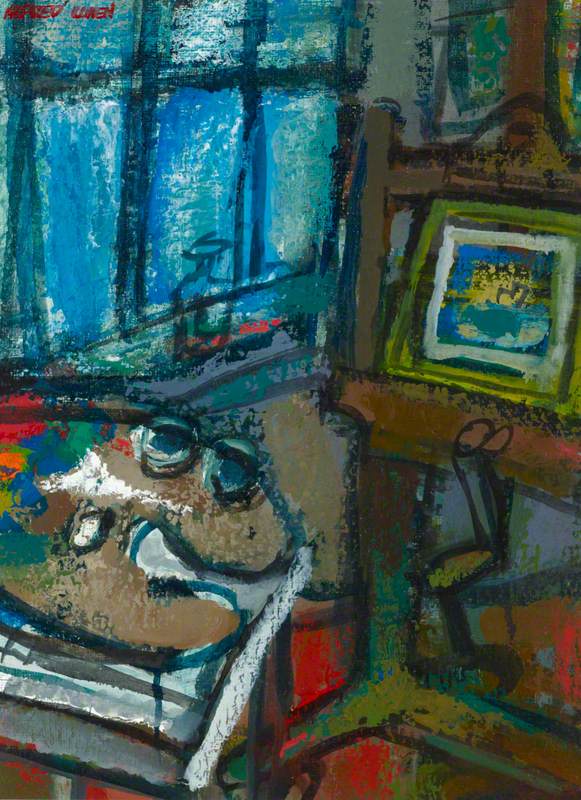

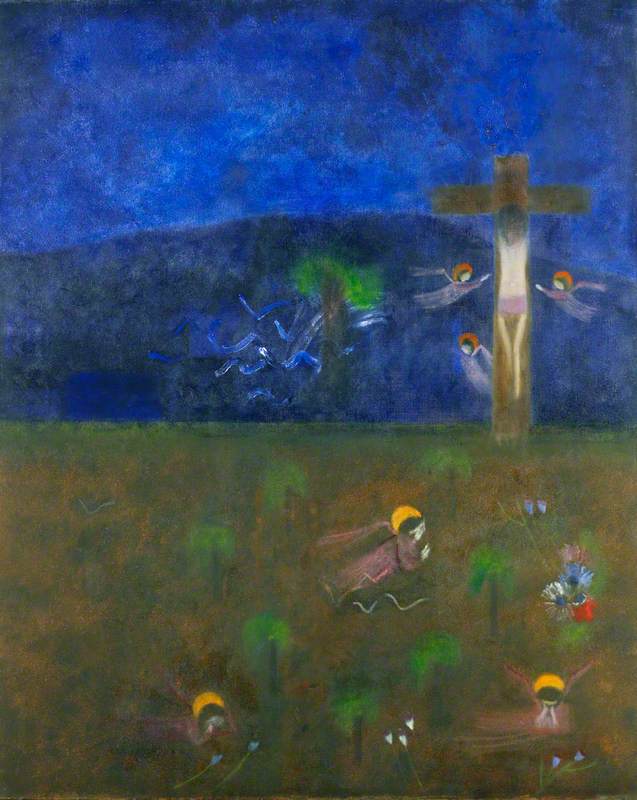

Self Portrait

early 1950s, oil on canvas by Alfred Cohen (1920–2001), Ein Harod Museum, Israel

He had moved to the city from Paris the year before, to a studio near the river in Chelsea. The artist showed an adventurous streak: a former Second World War flyer, who'd seen planes blow up in the air beside him, he hitched lifts on Thames tugs, and scaled the heights of scaffolding for the new Millbank Tower to sketch the view to St Paul's.

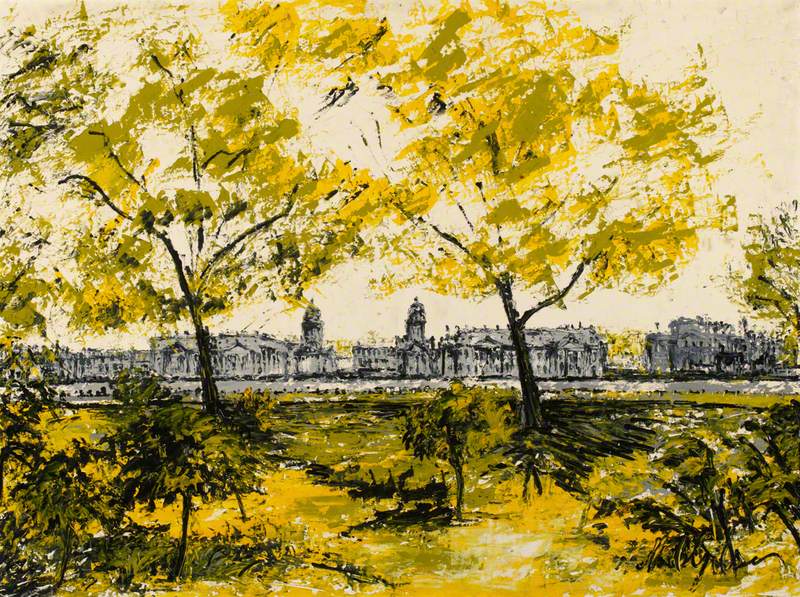

St Paul's, West View

1960, oil on board by Alfred Cohen (1920–2001), Sainsbury Centre, University of East Anglia

A London journalist dubbed Cohen 'the Spiderman Painter.' The young Anita Brookner, the Courtauld-trained art historian who would later become both Slade Professor of Art at Cambridge and a Booker Prize-winning novelist, was more seriously impressed by the bold blasts of colours in panoramas of the Thames and the London Docks. Writing in the Burlington Magazine, she called him 'a fresh and accessible artist of considerable accomplishment, whose abstract impressionist compositions were enlivened by an acute charm of colour.'

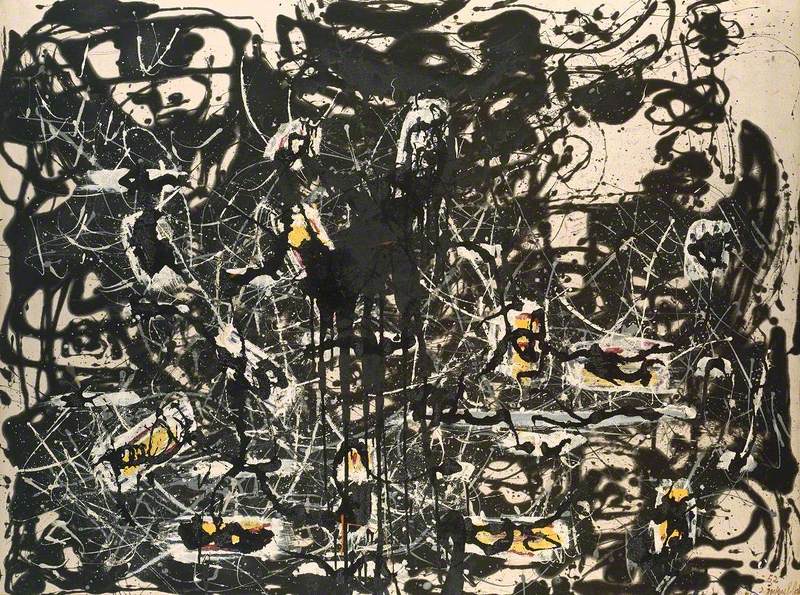

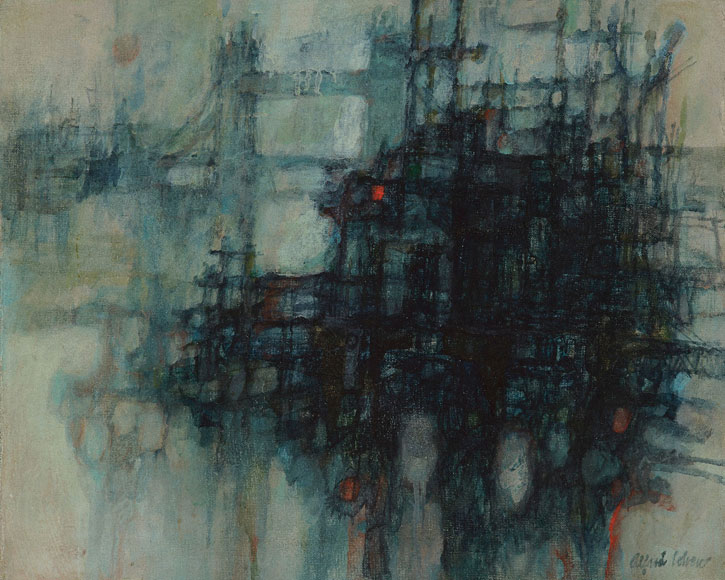

Wapping Pier and Tower Bridge

1961, oil on canvas by Alfred Cohen (1920–2001), Arts Council England

Begging the question, for almost every contemporary art critic: who was Alfred Cohen?

The first exhibition in nearly 20 years devoted to the artist, 'Alfred Cohen: An American Artist in Europe', opened in London in March 2020.

Showing at The Arcade at Bush House, a gallery space at King's College London, it closed the same day, the pictures still in place, due to the coronavirus outbreak. Two decades in conception and two years in the planning, bidding to restore his visibility and stature, the exhibition was to launch a major new book on Cohen, citing influences of Walter Sickert and Oskar Kokoschka. There were 50 paintings from across the UK and several from the US not seen for half a century.

Cohen was born in Chicago in 1920 to Latvian-Jewish emigre parents. He took evening art classes before volunteering during the Second World War for the US Army Air Corps, flying as a navigator from Guadalcanal in the hellish theatre of the Solomon Islands. He returned to train at the Chicago Institute of Art, and came to Europe on a travelling fellowship. A 1952 exhibition toured Germany under US Government auspices.

He found a romantic Left Bank studio in Paris, and met Ernest Hemingway in Pamplona, before moving to London, and later in life to north Norfolk.

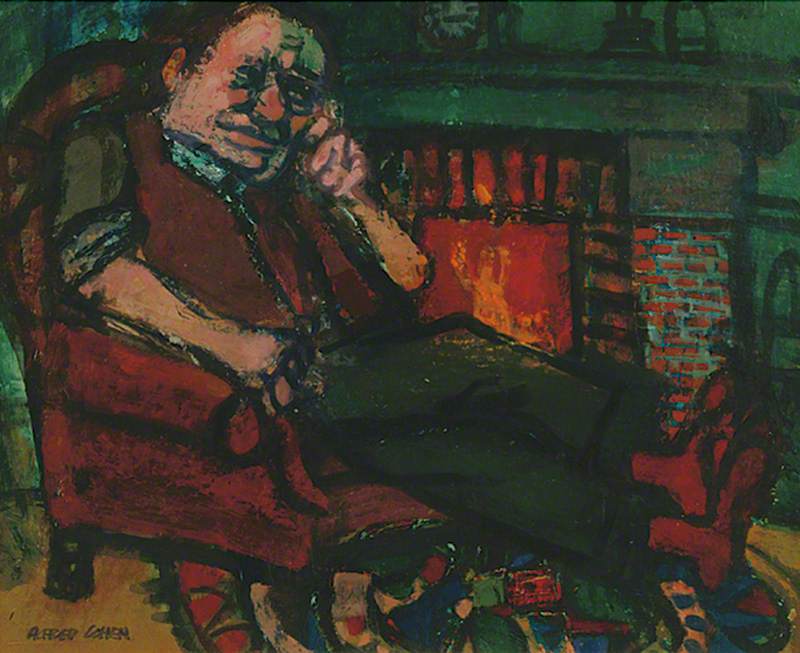

Art UK lists eleven works by Cohen, most in regional collections. The earliest dated acquisition is the Rye Art Gallery's Man at Ease, with a solitary, sober figure in end-of-day thought, red-socked feet up by a glowing fire.

It was bought in 1977 with the help of the Victoria and Albert Museum Purchase Grant Fund.

One later work stands out: the striking Evening Sky – Wells, of Wells-next-the-Sea on the north Norfolk coast. Blues, oranges and red sweep powerfully across the canvas in an abstracted sunset over sketchy shapes of coastal homes.

For those of us with memories of that era, Cohen's art found celebrity fans; he was a close friend of the actor Sir Anthony Quinn, of Zorba the Greek fame, painting and sculpting him. He went to Rhodes for the filming of The Guns of Navarone, met Quinn's co-stars Gregory Peck, David Niven, and painted Basil Rathbone, the early screen incarnation of Sherlock Holmes.

Alfred Cohen working on the bust of Anthony Quinn

Unknown photographer

Anita Brookner was not the only critic impressed by the 1960s London works. Brian Wallworth in Arts Review wrote of 'a fine wildness about Cohen's pictures' and James Burr in Apollo of 'a fierce passion... His emotional power and exuberantly vigorous response infuse his paintings with an intensity that makes much contemporary expressionism look feeble.'

So what happened to Cohen, and his work? He was recognised with sizeable obituaries in The Telegraph and The Guardian in 2001, but, until recently, some of his pictures could be picked up for a few hundred pounds.

Until now, few of his strongest works have found their way into public collections, and he suffers in exposure on this site as an artist who worked on paper as well as canvas. That may change. Several Cohen paintings have recently been acquired for the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts at the University of East Anglia, and three more are slated for the Arts Council England collection.

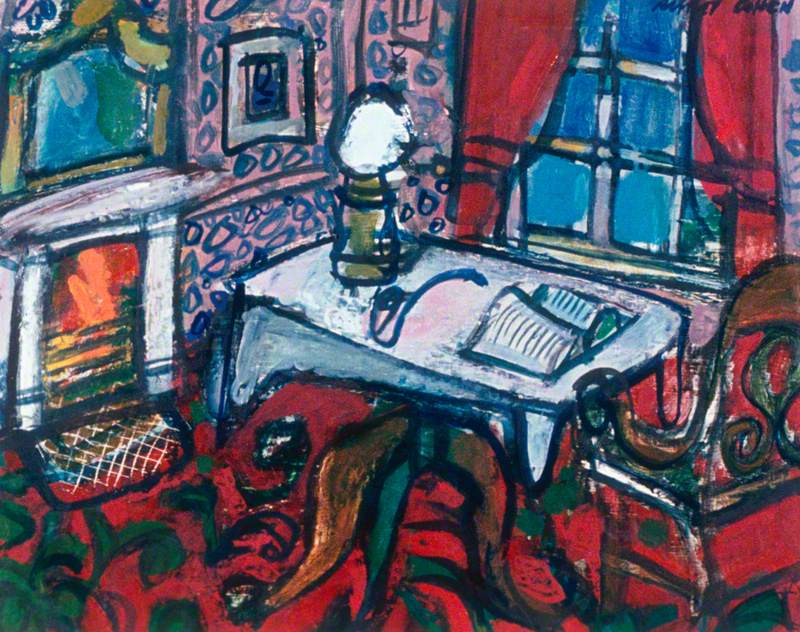

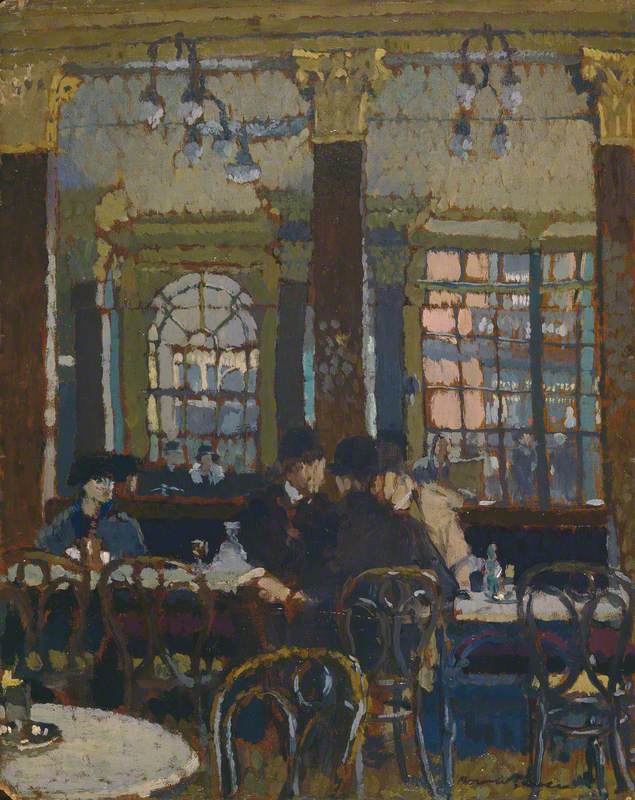

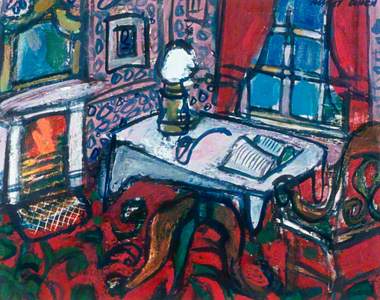

Les Championnes

1955, oil on panel by Alfred Cohen (1920–2001)

In the book released with the exhibition, Between Figuration and Abstraction, art historian Sarah MacDougall, head of collections and research at the Ben Uri Museum in London, and an expert on emigre artists in Britain, writes of one painting, Cohen's Sunset from Blackfriars Bridge (1961): 'In Cohen's Sunset, sky and river melt into one fiery whole, spreading out into the water until it too catches flame.'

Sunset from Blackfriars Bridge

1960, oil on canvas by Alfred Cohen (1920–2001), private collection

The artist's widow Diana Cohen, aged 90, travelled down from North Norfolk, where she has long run a small art gallery. But the opening night reception was cancelled as the global pandemic swept London's streets empty.

She walked with her stick between the rooms, devoid of visitors, as university staff locked down the building. Assembling and selecting the work for the show, preparing and framing the works, had taken 'ages', she said. 'I had to come, I had to see it here. It was going to be on for six weeks, now it's going to be closing tomorrow, because of this dreadful virus.'

Diana Cohen at the Alfred Cohen exhibition

'Alfred Cohen: An American Artist in Europe', King's College London

Art historians also writing on Cohen include the director of American paintings at the Courtauld Institute, and Paul Greenhalgh, director of the Sainsbury Centre. Museums with his work run from the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge to the French government collection, the St Paul Museum in Minnesota and the universities of Chicago and Wisconsin in the US.

But art and fashion changed radically in the 1960s. Cohen kept painting until close to his death in 2001, but he had moved on, to north Norfolk, and so did the London he left behind, to conceptual and Pop art.

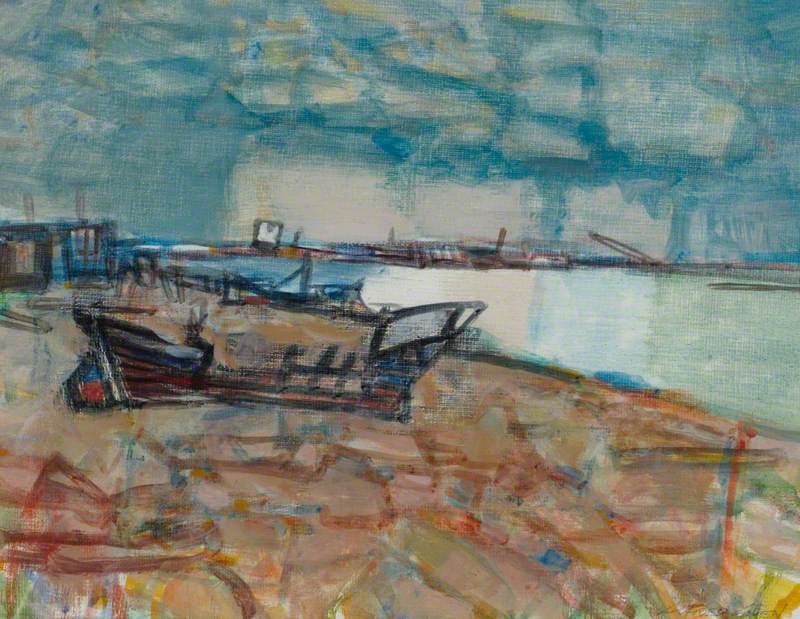

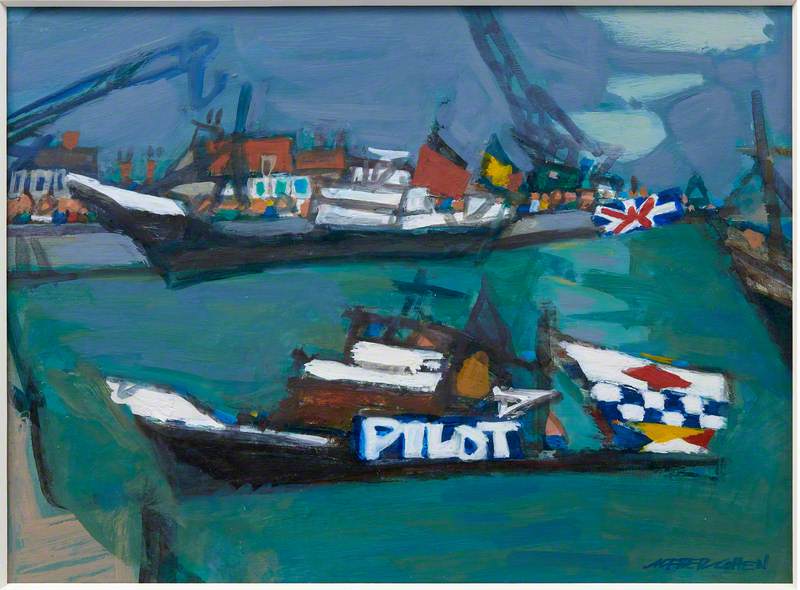

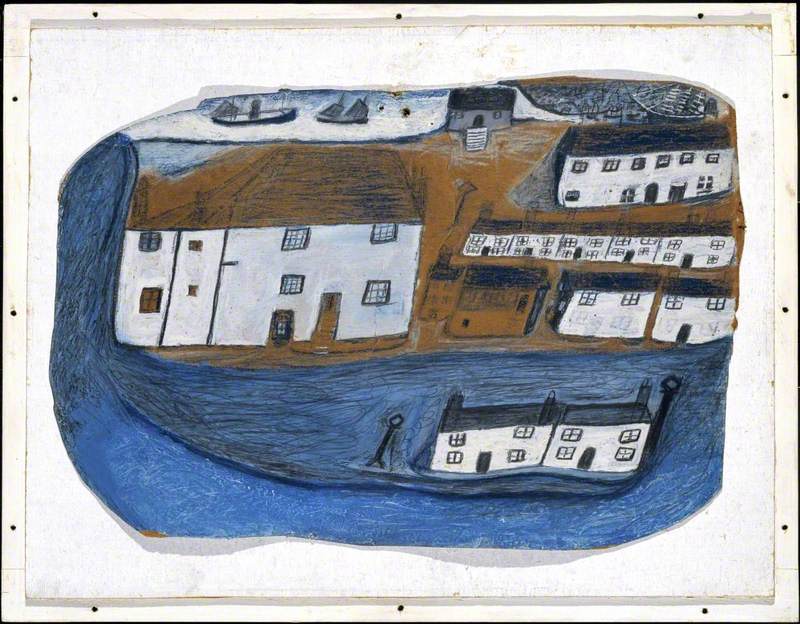

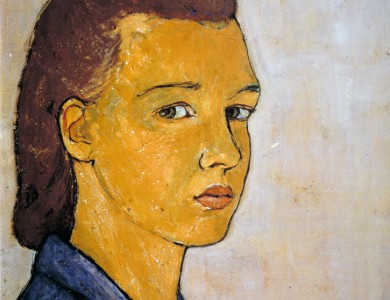

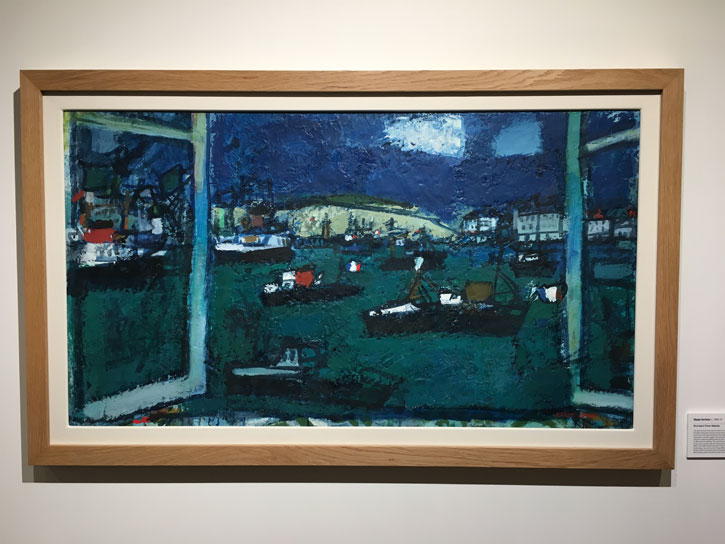

Sadly the exhibition had offered a chance to revisit a painter of a period in post-war British painting overshadowed by those that followed. Three other smaller centenary shows were due to follow; hopefully, they can still go ahead. The exhibition includes Dieppe Harbour.

Dieppe Harbour

1968–1974, oil on board by Alfred Cohen (1920–2001)

At a chance, you might question its seriousness. Then you admire the framing of those open windows, and close up, the thick layers of mottled, puddled, impasto. Put your face close against this work, as I did, and you're drawn deeply into it.

His stepson Max Saunders, the son of Mrs Cohen, began recording interviews with the artist 25 years ago, the model of a family archive for the Alfred Cohen Foundation.

'That's why I'm so heartbroken that the exhibition is not going to be seen by more people, because I have always thought you had to see the paintings on the wall to get a sense of the textures and the way the shadows fall,' he said. 'However good the posters are, you never quite get the full effect of that texture on the paint.'

'What people are saying now is that interest in figurative painting, and just in painting, is really coming back,' he added. 'There are art students saying please teach us about painting, the materiality of the techniques, they are less interested in installations and conceptual stuff than they were.'

'He used to say that it was noticeable that a lot of modern artists were painting enormous works for museums that no one could possibly buy or hang in their houses. He wanted the work to be liked and bought.'

Tim Cornwell, freelance arts writer

For more information about the exhibition, check the King's College London website

The related book by Max Saunders and Sarah MacDougall is available from ACC Art Books