Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975) is an artist who straddles the divide between the regional and the international.

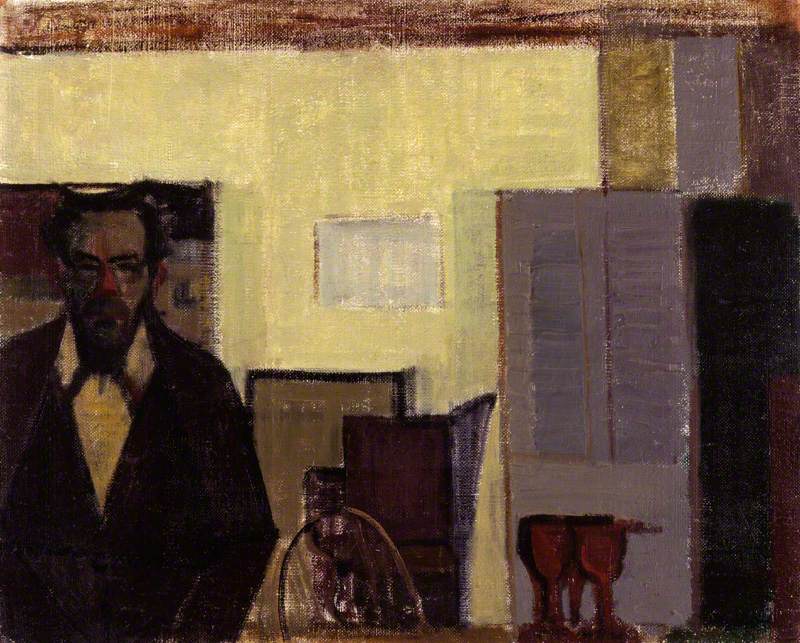

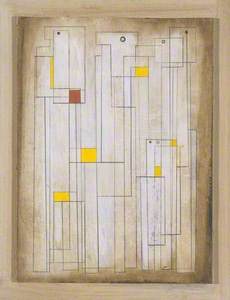

Though tied to her birthplace in Yorkshire and spiritual home in St Ives, and memorialised in both places with well-frequented galleries, she also spent a sizeable portion of her career in the cutting-edge set in London, living with fellow artist Ben Nicholson and active in the international avant-garde. She spent time studying in Florence, visited the studios of modern pioneers Picasso and Brancusi, and played host in London to such illustrious guests as Piet Mondrian and Naum Gabo.

However, despite her wide public appeal, and association with some of the greatest artists of her day, Hepworth still divides opinion when it comes to the critics. While Jonathan Jones calls her an 'idiosyncratic British artist of mostly local interest', hardly in the big league, Alastair Sooke names her 'one of our leading modernist sculptors'.

Curved Form (Trevalgan)

(cast three of an edition of six) 1956

Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975)

Hepworth's sculpture can be found dotted all over the globe, from Brazil, to Japan, Greece, South Africa, and a plethora in the USA. And it is not hiding away in shady backwaters; perhaps her most famous foreign export stands outside the UN Secretariat Building in New York. Whether or not you consider her talent 'provincial', her geographical reach can hardly be labeled similarly.

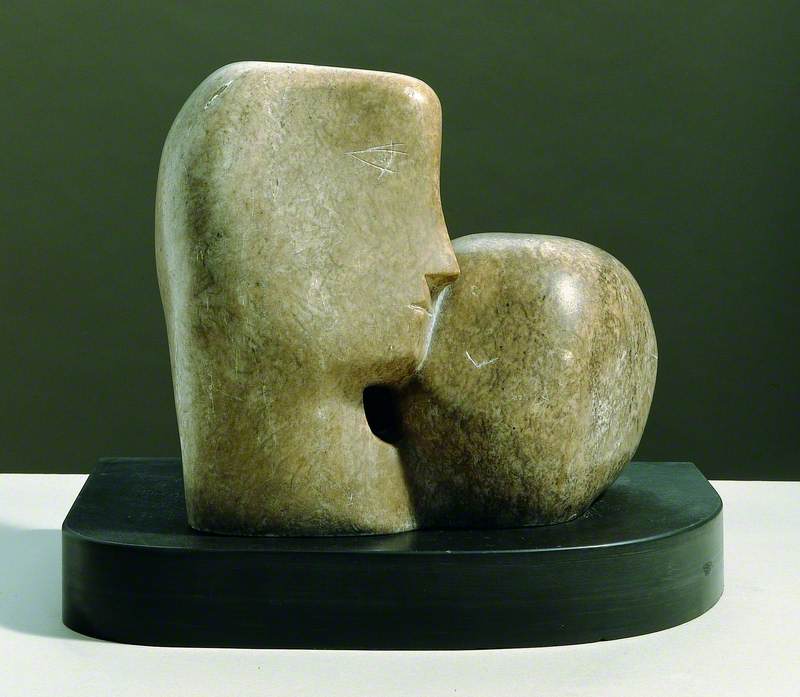

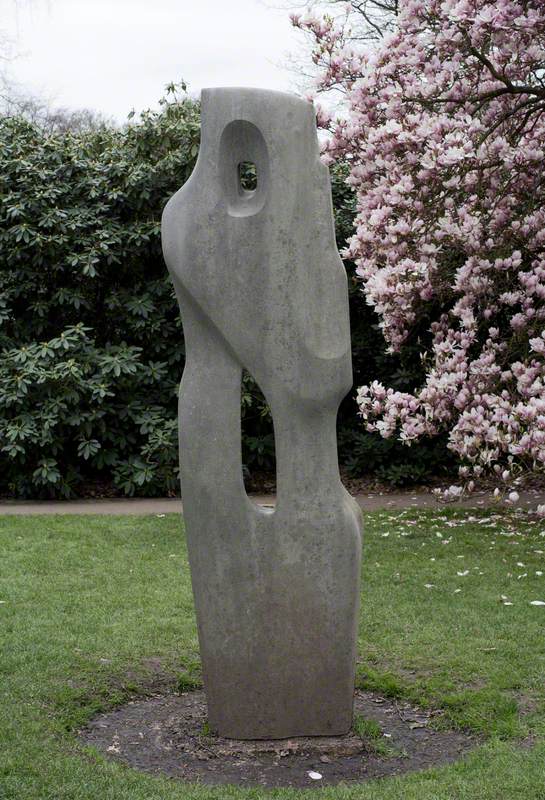

Dual Form

(cast four of an edition of seven, plus reserved copy) 1965

Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975)

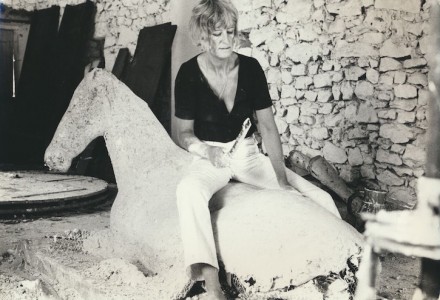

The spread of her work, and the high esteem in which it is typically held, are aspects made all the more impressive when one considers that during her career Hepworth was very much a woman in a man's world. This seems a somewhat obvious point to make, but in her case the struggle was two-fold, not only an artist, but a sculptor, and a sculptor on an often epic scale.

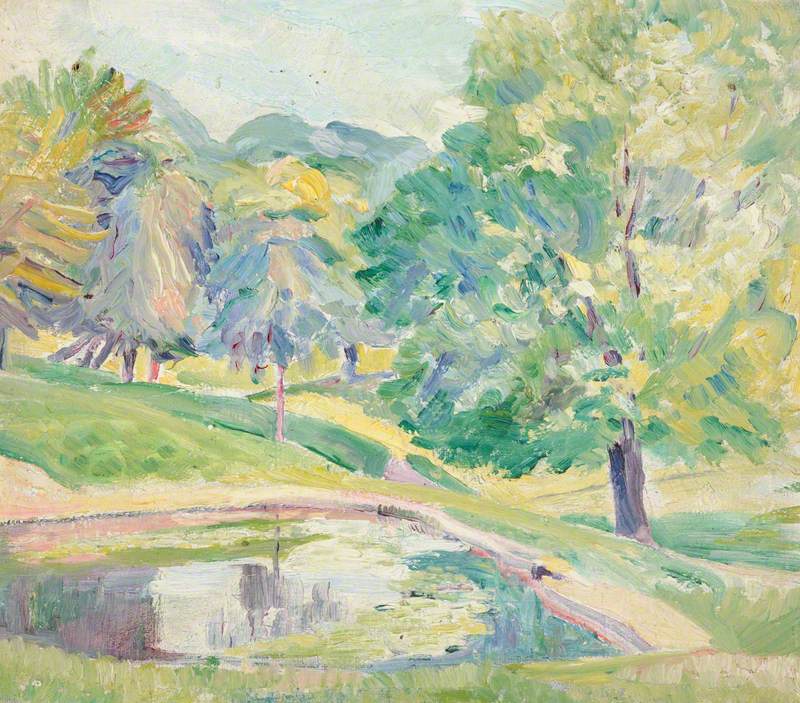

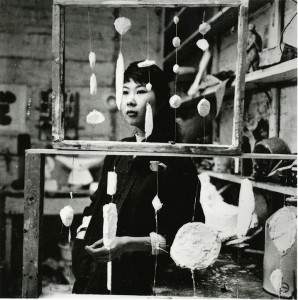

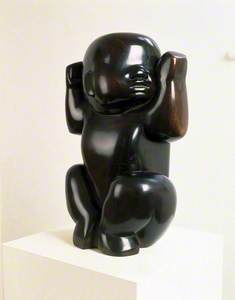

There is something arguably very macho about the way Hepworth made her works, through a method known as 'direct carving', going straight to the material with tools in hand excavating the hidden form within. She made no models, few maquettes, and few sketches, but this was not to say her ideas were not painstakingly formed in her mind before the carving began.

In a magazine extract form December 1932, she is quoted: 'An idea for carving must be clearly formed before starting and sustained during the long process of working; also, there are all the beauties of several hundreds of different stones and woods, and the idea must be in harmony with the qualities of each one.' Being true to the materials with which she worked, stood at the centre of Hepworth's practice.

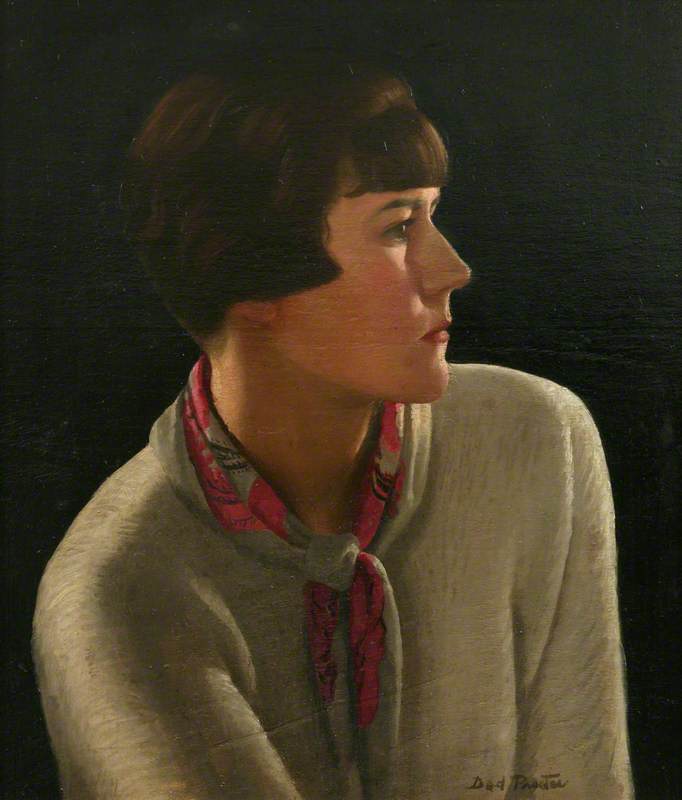

Although she avowed that art could be 'without gender', critics and commentators over the years, have struggled not to read her work through the prism of her femaleness, and it would be naïve to ignore. The biomorphic curves, and signature 'piercings' or 'voids' in her sculptures are often read as somehow inherently feminine, and her work has been disparaged for lacking Moore's 'tumult', a distinctly sexist criticism.

Her approach to sculpting was one of collaboration rather than supremacy, a realisation she had when studying in Italy: 'A chance remark by Ardini, an Italian master carver whom I met there [in Rome], that "marble changes colour under different people's hands" made me decide immediately that it was not dominance which one had to attain over material, but an understanding, almost a kind of persuasion.'

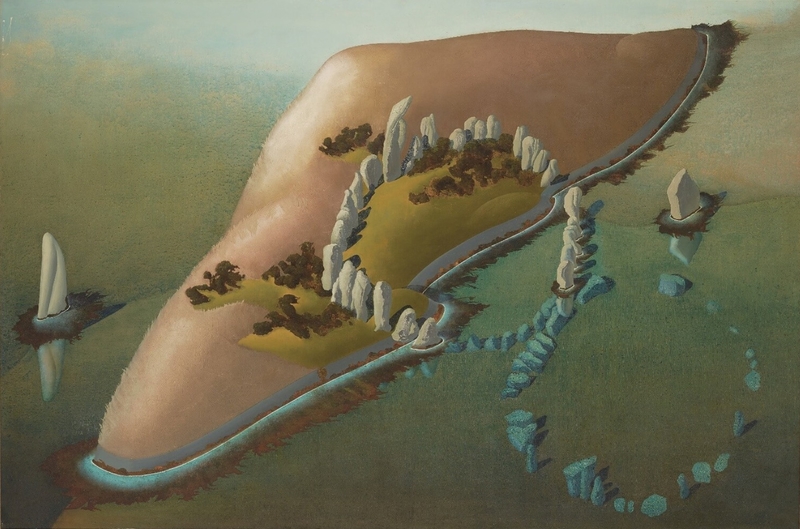

Her interest in the body, in the abstract nature of both inner life as well as exterior form, and her characteristic 'holes', draw us into a contemplation of the void, of the spaces around which grow her marvellous forms. There is a concentration of focus, of energy, into the missing element, the hollow which seems at first like emptiness but could not be further from it.

Parallels have been drawn on this subject between the idea of womanhood, of the female as defined by absence rather than presence, a notion both articulated and exposed as falseness in Hepworth's sculptures where, as she wrote, the voids are expressions of an abstract 'spiritual vitality or inner life, which is the real sculpture'.

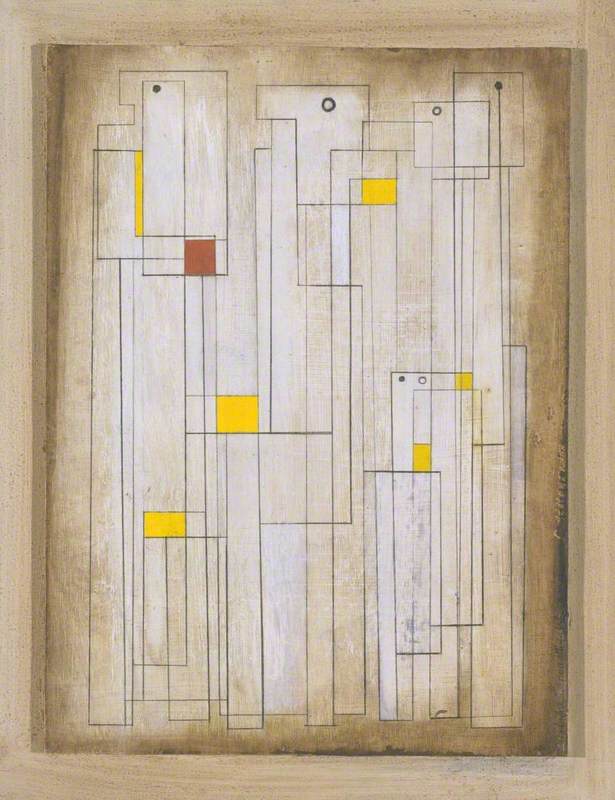

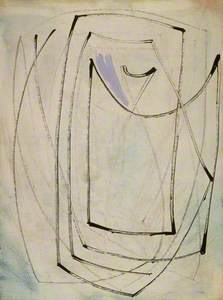

Orpheus (Maquette I)

(cast four of an edition of eight) 1956

Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975)

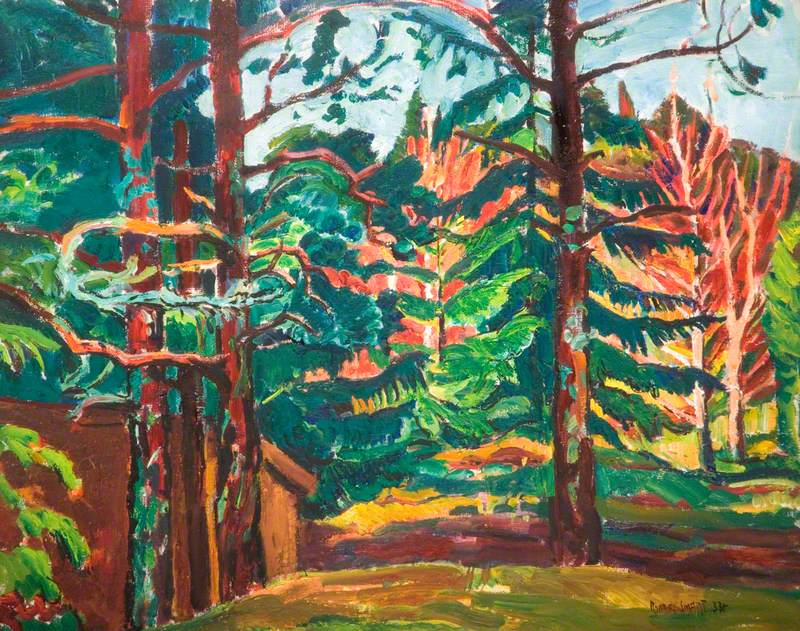

In 1949, Hepworth's sculptural works took on another of what was to become their signature motifs: the use of string. It was after a meeting with composer and musician Priaulx Rainier, that Hepworth began to explore the use of stringed passages in her work.

There is a conversation in these works around the ambitions of sculpture and the capability of music, it is a conversation had over centuries, but the element that most intrigued Hepworth was the creation of tension, the feelings of connectedness and anxiety inspired in her by the Cornish landscape, equal parts pastoral and epic.

She wrote: 'The strings were the tension I felt between myself and the sea, the wind or the hills. The barbaric and magical countryside of rocky hills, fertile valleys, and dynamic coastline of West Penwith has provided me with a background and a soil which compare in strength with those of my childhood in the West Riding.'

Torso III (Galatea)

(cast six of an edition of seven) 1958

Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975)

Hepworth's connection to place is unwavering, and as such the inclination to position her as a 'regional' or 'provincial' artist is not exactly wrong, but seems to suggest a degree of parochialism or conservatism which is far from apt. Her inspiration, taken from both the human form and the landscapes which foster it, became as much a part of the physical act of direct carving, as the cerebral act of creation. With Hepworth the two meld and join such that the idea and the activity are one and the same.

She called her left hand, her 'thinking hand'. 'The rhythms of thought,' she said, 'pass through the fingers and grip of this hand into the stone.' Despite her trademark voids, her pieces have a wholeness that testifies to this seamless marriage between inspiration, material, and practice.

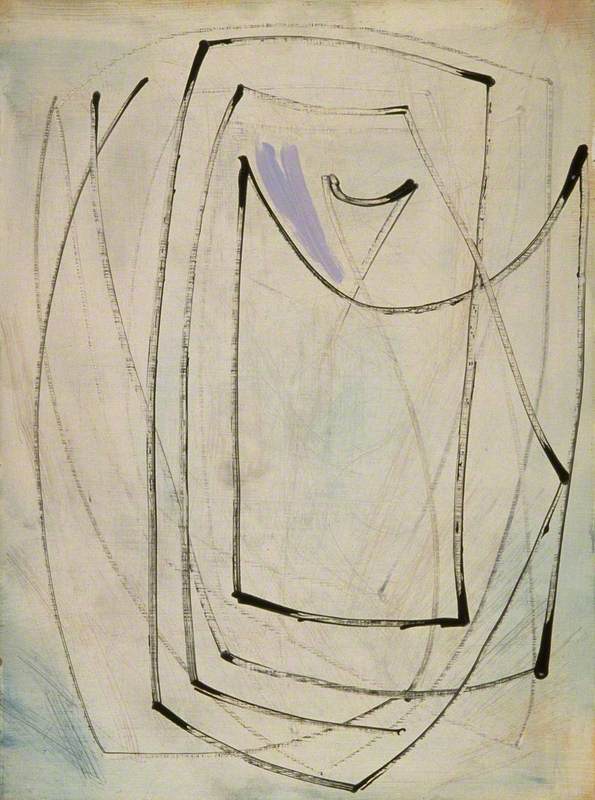

Oval Form (Trezion)

(cast two of an edition of seven, plus reserved copy) 1961–1963

Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975)

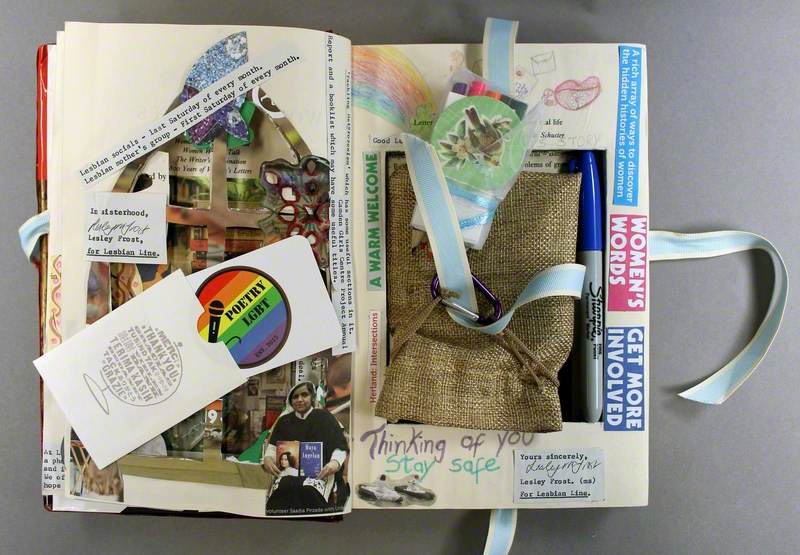

Hepworth's outlook in life was a socially engaged one. She lived through two World Wars, first as an infant, then an adult, the Spanish Civil War, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Cold War. The atmosphere and lexicon of conflict must have been all too familiar, and yet, like her great friend and rival Henry Moore, her public sensibilities and commitment to collective problem solving were of utmost importance.

Hepworth was a member of the Labour Party, and of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, and her faith that art had an equally strong personal and communal message to bestow, is played out by the prevalence of her works in public collections and spaces. When some years ago Hepworth's old school in Wakefield sold two of her sculptures to raise money for student bursaries, one imagines that though grieved at the necessity, she may well have understood.

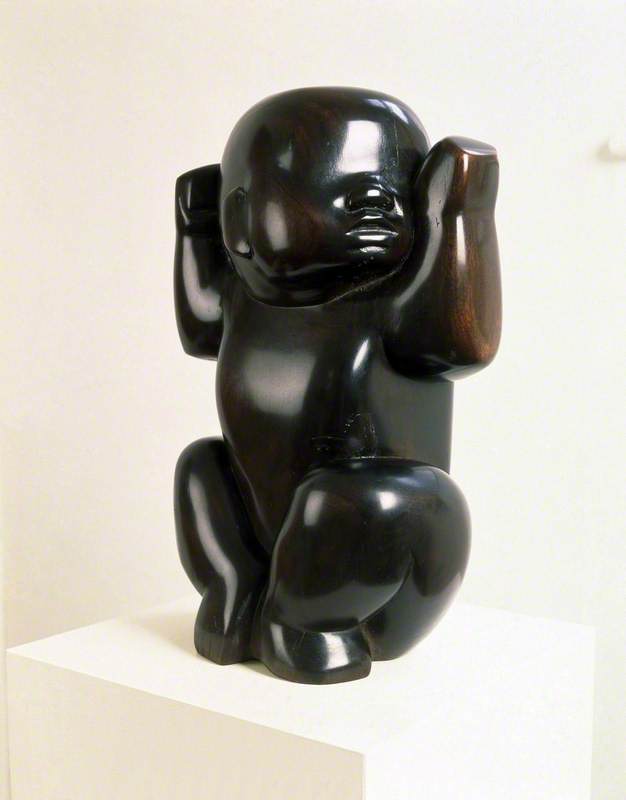

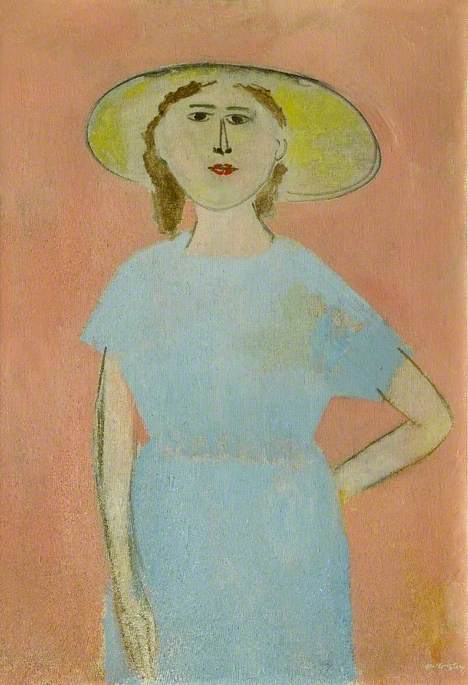

Hepworth's personal life was, as are all our lives, speckled with happiness and tragedy, and some of these events find their way into her work.

From the emboldened upright baby, made shortly after the birth of her son, Paul, to the Madonna and Child carved after his death in a flying accident in 1953, and the tall figure of Monolith (Empyrean) created in the same year.

In the latter, the standing stone is so very nearly abstract, and yet, somehow, the human qualities ring clear and we sense that this cold slab of a body carries the trademark void in place of the solid stony flesh of a belly.

Single Form (Eikon)

(cast six of an edition of seven, plus reserved copy) 1963

Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975)

Hepworth's work, at once deeply personal and sublimely universal, has inspired many an artist after her, with two galleries already dedicated to her work, and 2016 saw the founding of a prize in her name. It is set to be one of the most prestigious art awards around, but the organisers have been careful to differentiate it from others. The prize can be awarded to an artist from anywhere in the world at any stage in their career, as long as they are producing work in the UK.

It is thus a fitting tribute to an artist whose outlook was so concerned with the universal and the collective but who found such inspiration in the world immediately surrounding her.

Kate Devine, art historian