You could be forgiven for thinking that modern British art belongs firmly in the past, with contemporary artists preferring to look beyond these shores for inspiration. In this postmodern moment, artists have opportunities to engage with a global tapestry of sources. Nevertheless, it is intriguing to discover that a significant number of UK-based artists have responded directly to modern British art within their work. My essay in the new book Revisiting Modern British Art explores some of these connections.

Often it is a particular motif, a technique, or a shared mood, that provides the catalyst. At other times, artists have stepped back in time to question established narratives. These interactions dislodge the myth of modern British art as the artistic equivalent of rambling around a rusty old pier, replacing it with a fresh notion of the period as a springboard for fresh thinking.

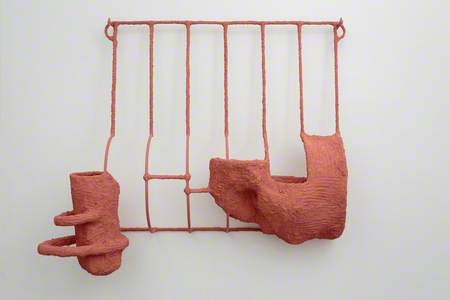

An obvious way to influence the next generation is through teaching. It is said that you never forget a good teacher, and this dictum certainly applies to the sculptor Phyllida Barlow (1944–2023). She drew considerable inspiration from her tutor, the sculptor George Fullard (1923–1973), during her time as an art student at Chelsea School of Art.

Fullard's unorthodox teaching methods involved looking beyond the art world to cartoons and slapstick comedy in search of happy accidents and material collisions. These lessons in the absurd have made a lasting impact on Barlow's playful approach to sculpture and informed her own development as an engaging teacher.

Employing studio assistants provides further opportunities for mentorship. Anthony Caro (1924–2013), who himself once worked in Henry Moore's studio, was well known for his desire to nurture enlightening conversations with his extensive team of assistants.

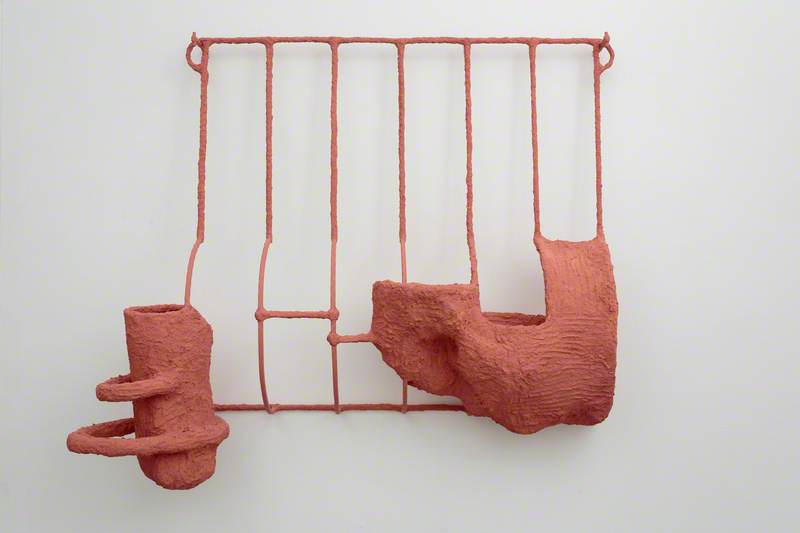

The sculptor Olivia Bax (b.1988) worked with Caro towards the end of his life. It is interesting to observe the points of connection and departure within her work. Her dynamic, brightly coloured sculptures nod to Caro's lyrical mode of abstraction. Yet, her incorporation of found, malleable materials such as chicken wire and pulped newspapers provides a suitably playful riposte to the seriousness of steel.

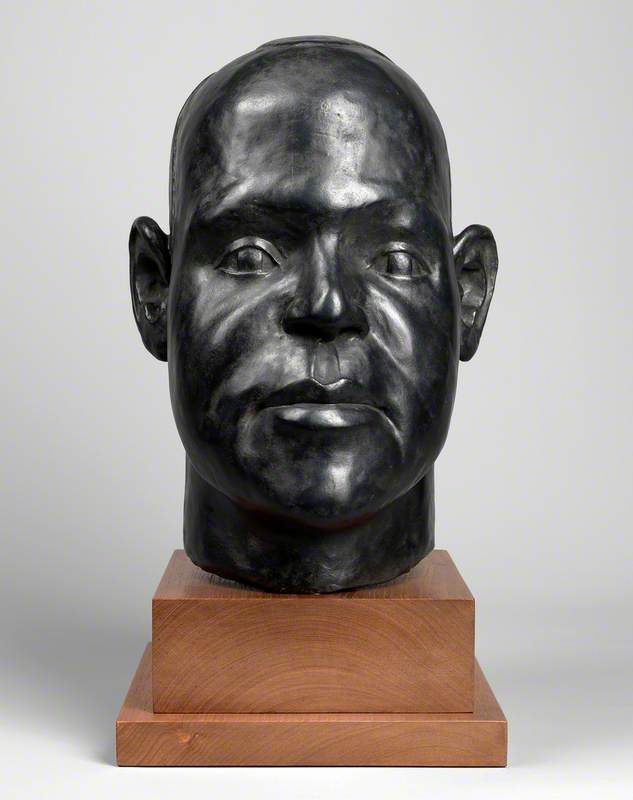

Of course, artistic relations with the past are not always harmonious. The most prominent figures in modern British art have endured the greatest ribbing. Take Henry Moore (1898–1986), for example, whose ubiquitous oeuvre has been critically reappraised by a range of artists including Bruce Nauman (b.1941) and Simon Starling (b.1967).

In 1971, Bruce McLean (b.1944) famously performed his Pose Work for Plinths at the Situation Gallery in London, draping himself across a series of white plinths in a manner reminiscent of one of Moore's reclining figures.

Art Term of the Week: Live Art

— Tate Collective (@TateCollective) May 15, 2021

The term live art refers to performances or events undertaken or staged by an artist or a group of artists as a work of art, usually innovative and exploratory in nature.

Bruce McLean Pose Work for Plinths I 1971 Tate © Bruce McLean pic.twitter.com/8xXrnXcNjf

More recently, artist Des Hughes (b.1970) has updated the reclining figure idiom with a wry twist. In 2015 he created a new sculpture for a school in Castleford, a town notable for being Moore's birthplace, and for its connections with rugby league.

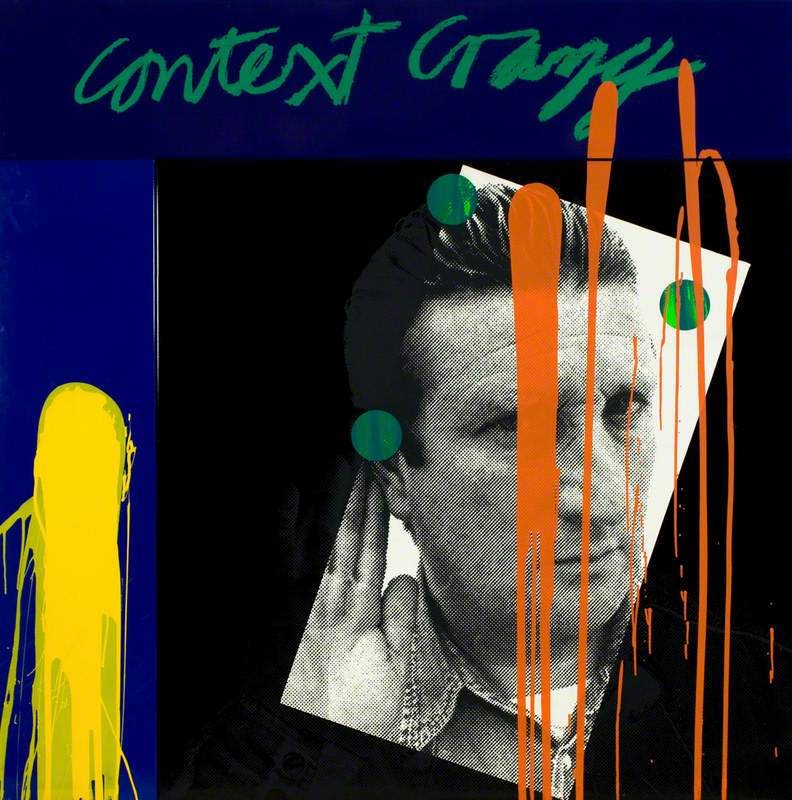

Several artists have referenced specific examples of modern British art within their work. This strategic appropriation has led to new possibilities. The painter Glenn Brown (b.1966) was warned repeatedly during the 1990s that painting was dead. Keen for a resurrection, Brown looked back through the art history books for appropriate source material. He was struck by the work of Frank Auerbach (b.1931), whose paintings are notable for their rich impasto surfaces.

Using special brushes and working meticulously from reproductions, Brown's versions of Auerbach's portraits of Juliet Yardley Mills are super-flat, precise and deeply uncomfortable. As Brown acknowledges, 'My slowly painted detail encapsulates the flesh of the figure like a painstaking autopsy.'

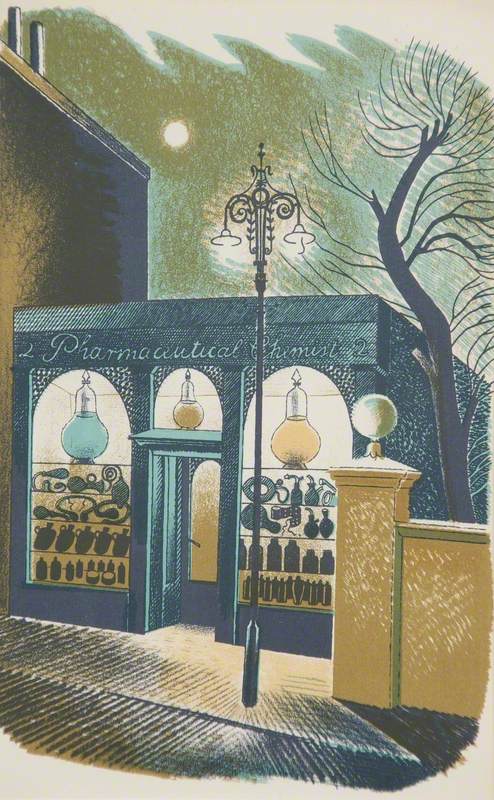

A similar spirit of loss infuses the landscape paintings of Clare Woods (b.1972). Using oil paint on large sheets of aluminium, Woods establishes a magical twilight world found deep beneath the undergrowth.

Again, it is possible to pick up on the scent of the past, this time the Neo-Romantic paintings of Graham Sutherland and Paul Nash. Their melancholic and poetic representations of the British landscape seem to bear the deeper scars of wartime trauma. Woods captures the mood of this brooding imagery and reflects upon its contemporary significance.

Sometimes revisiting an artist’s workspace can trigger fresh points of connection across time and place. There are several examples, including the visit of Lucy Skaer (b.1975) to the home of the surrealist artist Leonora Carrington (1917–2011) in 2006, and the recent exhibition of paintings responding to the rich context of Charleston by Lisa Brice (b.1968).

View this post on Instagram

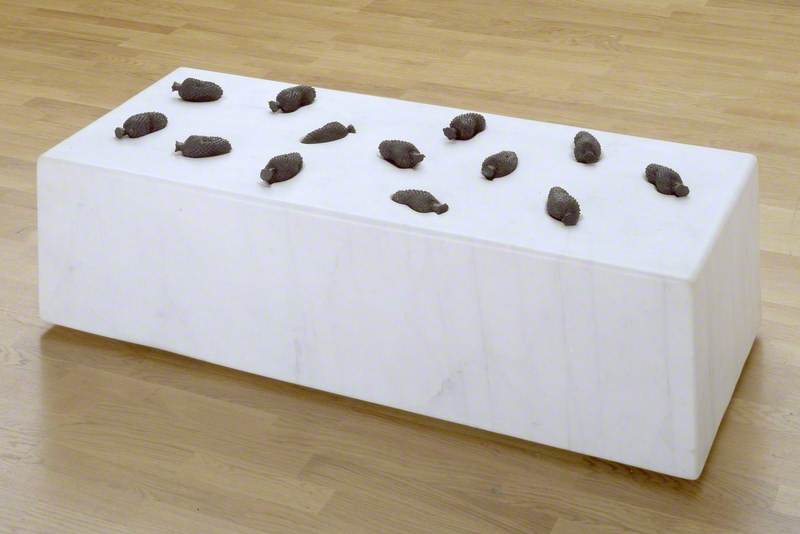

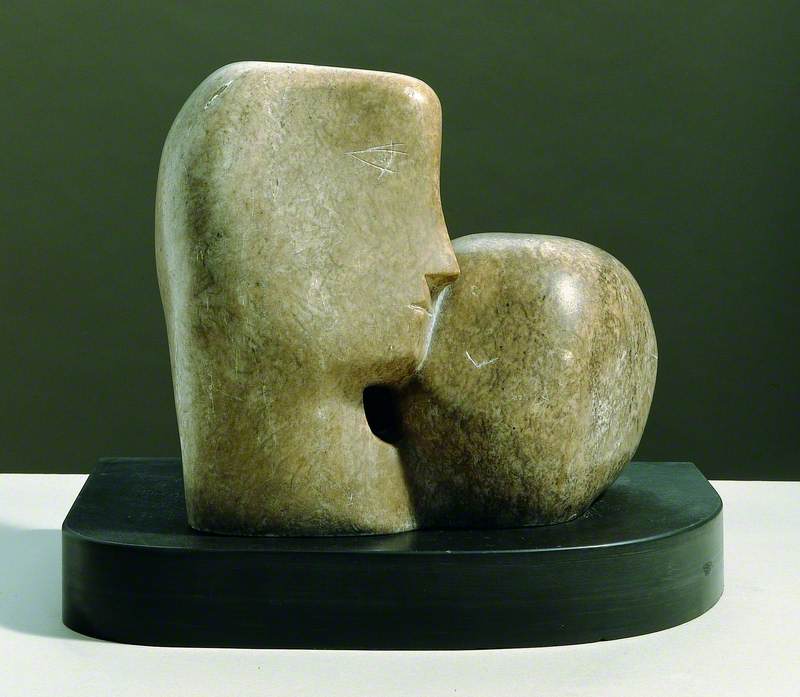

In 1998, the Montserrat-born British sculptor Veronica Ryan (b.1956) commenced a residency in Barbara Hepworth's Palais de Danse studio in St Ives, Cornwall and enjoyed the feeling of having 'a friendly muse around.' The discovery of a magnolia tree in Hepworth's Sculpture Garden prompted Ryan to contemplate the similarities between its pods and the soursop fruit, which Ryan had first tasted as a child when revisiting her place of birth.

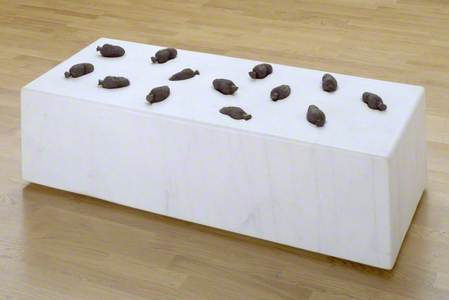

Working with donated offcuts of Hepworth's Carrara marble, Ryan created Quoit Montserrat, a reliquary of sorts – a place to hold thirteen cast silicone rubber pods, and to reflect on issues of time, memory, movement, and shared artistic concerns.

Sometimes, the process of looking for points of influence feels a bit like hunting for ghosts. There is a lightness to this pursuit, reflecting the very nature of inspiration, which often arrives in short bursts or gets obscured by other layers of reference.

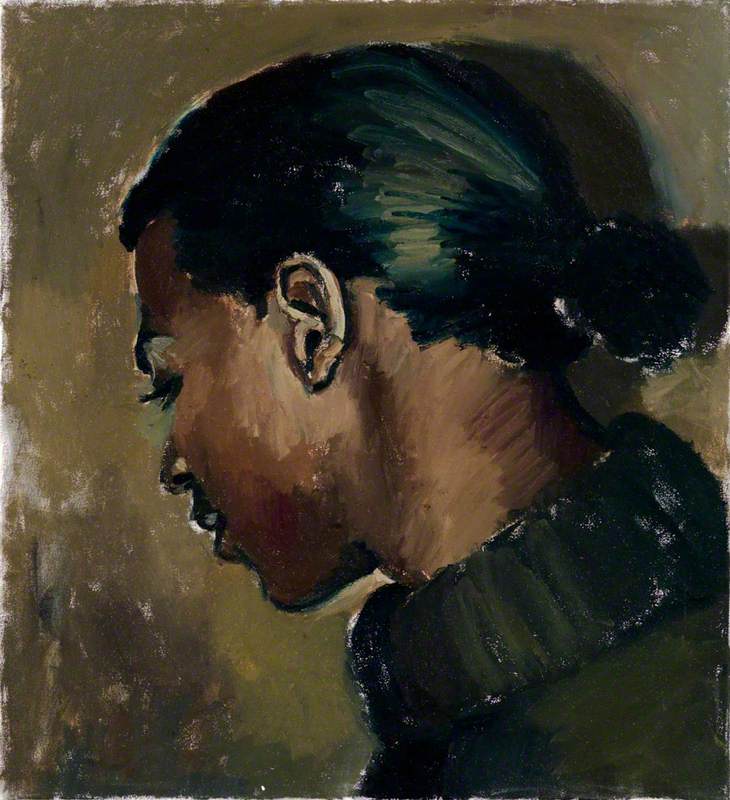

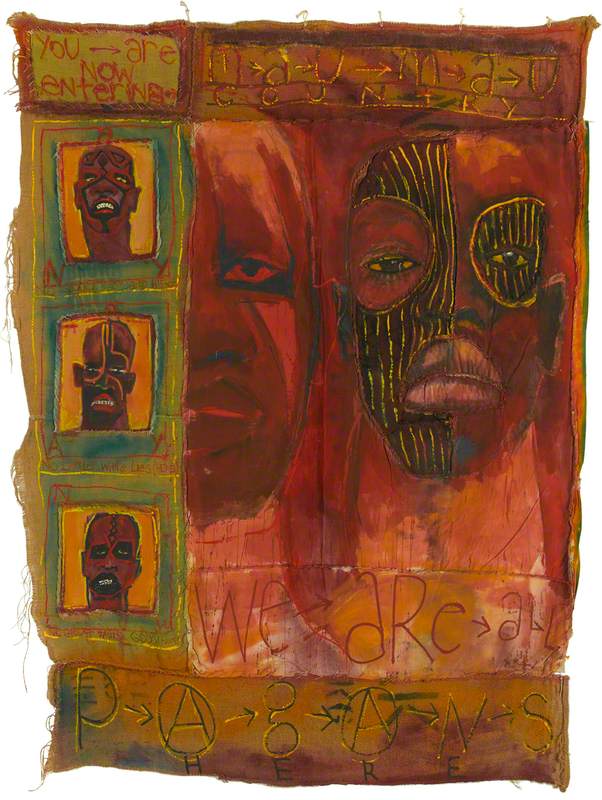

Take, for example, the work of the British artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (b.1977). Her striking paintings of Black people engaged in acts of deep reflection have achieved international recognition in recent years.

Look carefully and it is possible to glimpse a clear nod to the modern British artist Walter Sickert (1860–1942) – to his languorous, bored figures, slumped in gloomy settings.

Reflecting Sickert's working methods, Yiadom-Boakye prefers to complete a work within the same day, painting wet on wet, capturing the joyful freshness and energy of the medium. There are ghosts to be found in the poses and gestures, and in the processes of making.

Given the range and dynamism of these creative interactions with the past, the legacies of modern British art appear well established. There are more connections to be uncovered, and many others still to unfurl as the next generation of artists encounters this rich seam of art history.

Natalie Rudd, curator and writer

Revisiting Modern British Art, edited by Jo Baring, is published by Lund Humphries on 10th October 2022