Download and subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher or TuneIn

Art Matters is the podcast that brings together pop culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

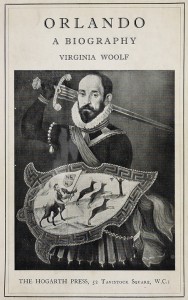

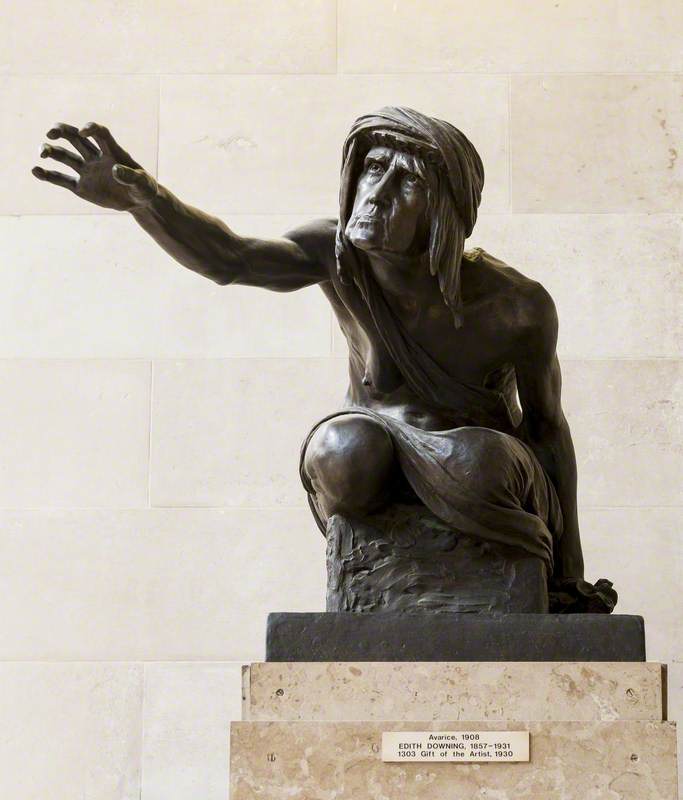

There’s a touring exhibition titled 'Virginia Woolf: An Exhibition Inspired by Her Writings' that began at Tate St Ives and is currently at Pallant House Gallery until 16 September 2018. It’s an exhibition that features artworks inspired by the life and writings of Virginia Woolf, but it also examines women artists’ portrayal of self, the legacy of women in the history of art, and the idea of what makes a feminist exhibition.

This type of show throws up several questions: What is feminist art? What is the female gaze versus the male gaze? And what steps can art critics and historians take to rebalance gender inequity in the art sector? I thought the best place to start to address these questions was by speaking to Laura Smith, curator of Whitechapel Gallery and former curator at Tate St Ives where she organised the Virgina Woolf exhibition.

If I put Virginia Woolf in the centre of an imagined history and traced forwards and backwards from her, what might that history of women making work in the visual arts – in literature, in music, in dance and in performance – what does that look like?

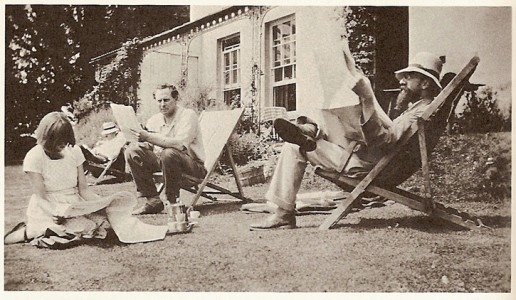

‘I was interested in finding ways to bring more women artists into Tate St Ives’ programme and Tate St Ives was founded with the mission to speak to the history of visual artists working in St Ives at the turn of the century and through to high modernist period,’ says Laura. ‘What the gallery hadn’t done so much was talk about the literary history of the area and how some fairly significant modernist writers were also living and working in and around St Ives, such as Virginia Woolf… These writers were as much a part of the Bohemian idea of St Ives as the artists working there. I wanted to use Virginia Woolf and her feminism as a way of citing an exhibition of work by predominantly women artists in a context in which a lot of it was inspired and made.’

The exhibition features women artists and is centred around Virginia Woolf, who became something of a feminist icon from around the 1970s. It includes women who were associates of Woolf, artists who’ve cited her work as inspiration, and works by artists with themes that relate to ideas of feminism and women’s creativity. I wondered if that context made the exhibition fundamentally feminist rather than an exhibition than simply featured female artists – as the two don’t necessarily go hand-in-hand.

‘If I put Virginia Woolf in the centre of an imagined history and traced forwards and backwards from her, what might that history of women making work in the visual arts – in literature, in music, in dance and in performance – what does that look like?’

‘I think the exhibition is a feminist exhibition, but not necessarily all of the artists in it would see themselves as feminists, and I think that’s fair and that’s up to them,’ says Laura. ‘There are so many women in this show who deserve to be exhibited more. Yes, Woolf wouldn’t have used the term [feminist] because it wasn’t really around when she was working, but if you read A Room of One’s Own, if you read Professions for Women, if you read Three Guineas – Three Guineas in particular – she’s fierce about women’s rights.’

Laura mentions that Woolf wouldn’t have described herself as a feminist and it’s important to remember that, when discussing topics like queer artists or feminist artists, many terms we use around these topics today have come into use more recently. It’s from Woolf’s passions and writing that we’re able to bring her into the feminist discussion, but we should be cautious of labels.

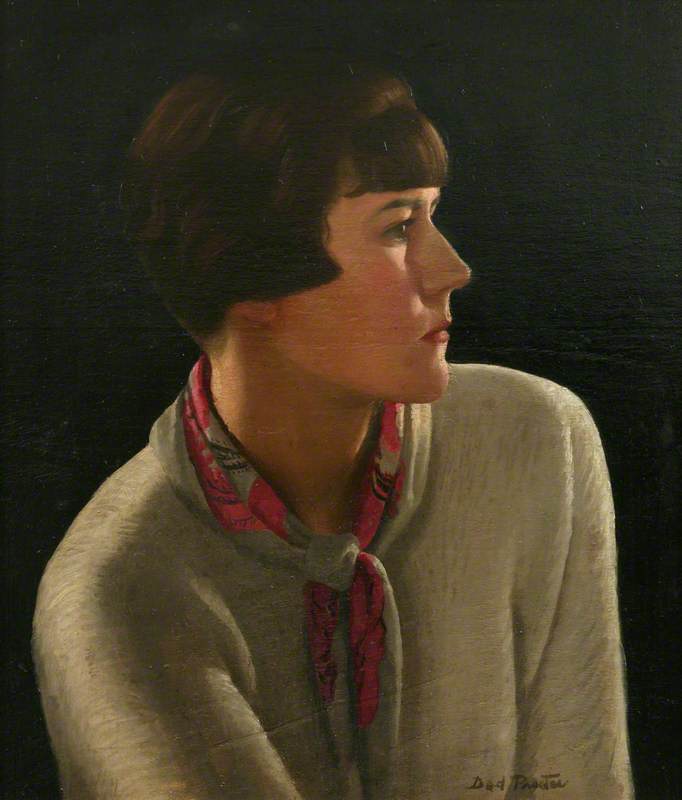

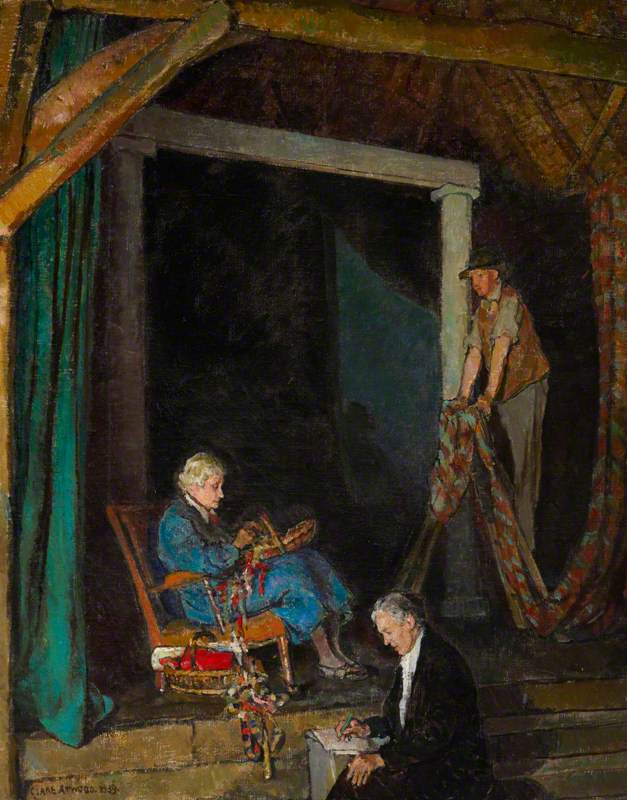

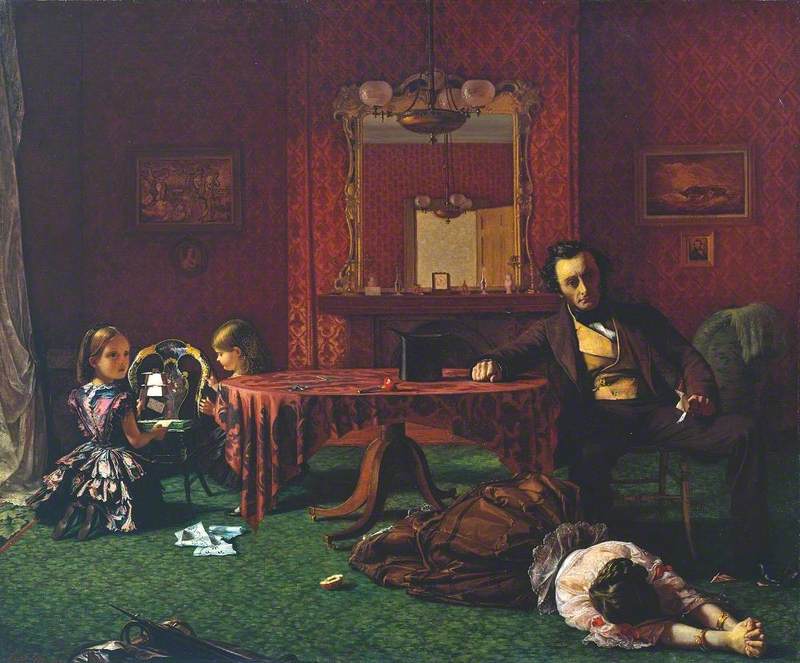

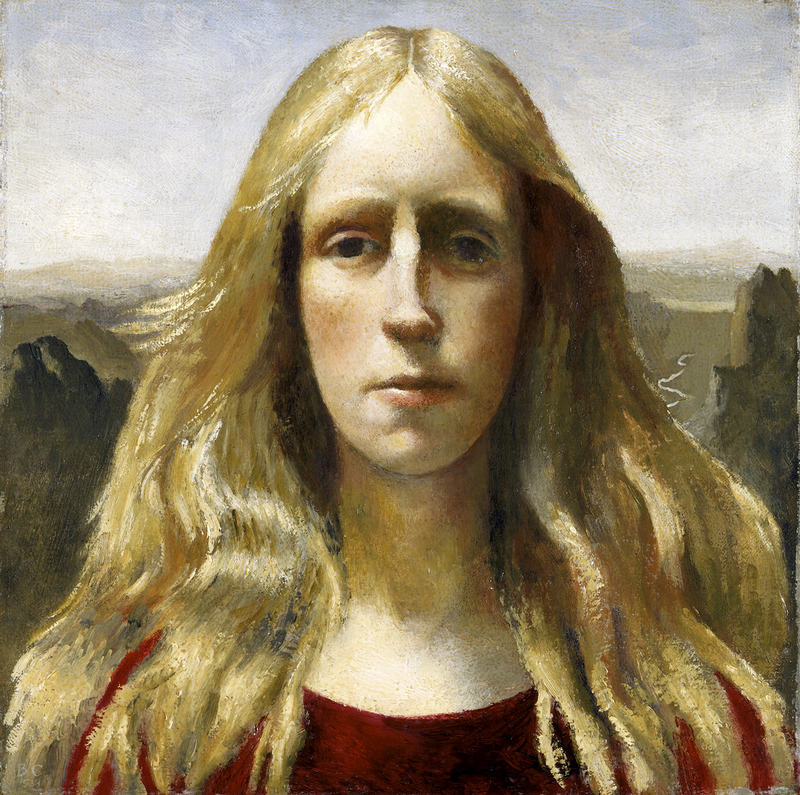

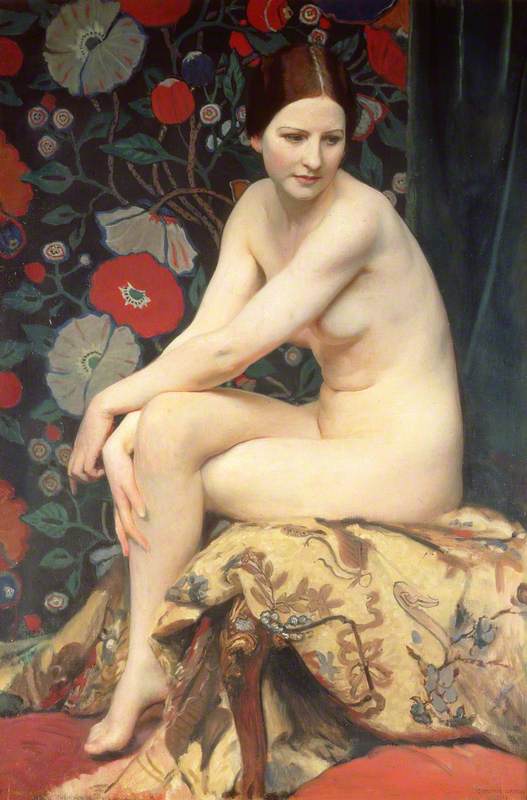

There’s a long, documented history of men painting the female form. One of the areas that struck me most about this exhibition was the idea of exploring the different ways that women represent themselves in paintings compared to men. Is there a difference and, if so, what is the sub-context of those differences?

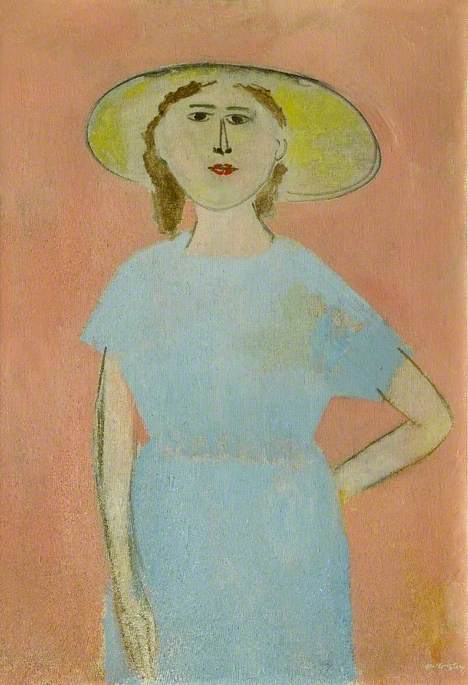

Self Portrait in a Hat with a Basket of Vegetables

1951

Clare Atwood (1866–1962)

‘I had in my mind for a long time this long wall of self portraits and portraits of and by women staring out at you,’ Laura explains. ‘What I found really interesting was that when they were painting themselves they often painted themselves in moments of contemplation or seriousness or looking fairly forthright – they didn’t beautify themselves, basically.’

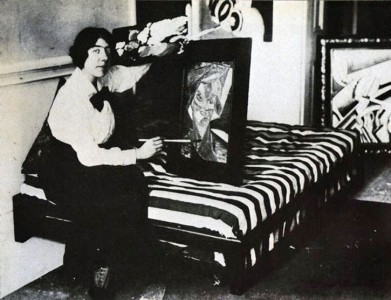

Venetia Berry is a contemporary artist whose work often includes nude female figures. I spoke with her about what this imagery means to her and how it might be different from some of the ways that we’ve seen female nudes depicted in art history.

‘My work isn’t based on a particular race, it’s not based on an age – I want it to reflect the ‘every woman’ experience and to be relatable to women,’ says Venetia. She discussed with me how female nudes were historically painted for a male audience, and told me how – as an artist who frequently paints this subject herself – she was asked why she paints ‘sexual paintings’. ‘I said I’m not painting sexual paintings, but people assume that because I’m painting a female nude, it’s going to be sexualised. I just want to take that sense of sexuality away from the female nude and, instead, celebrate the female form.’

It seems that there’s a sense of ownership and empowerment in women painting themselves, but there can be a quiet power found in other subject matters too – even a still life in a window can be loaded with meaning.

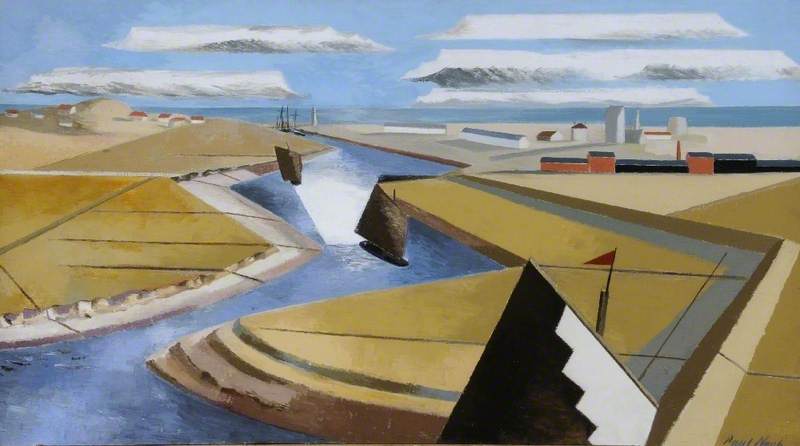

Laura explained to me that in A Room of One’s Own, Woolf explores ideas around being inside and outside, and how the interiors can represent confinement, and the outside can symbolise freedom. ‘What I wanted to do with the show was to mirror that. At the start of the show there’s a section about landscape and depictions of landscape that play with the experience of it,’ says Laura. ‘And then there’s an interiors section that’s much quieter and contained.’

Sitting somewhere in between the interior and landscape paintings, Laura discovered an interesting genre of paintings that straddles the line between the two, called window sill still lives. ‘It’s a still life painting – often of a vase flowers or some shells – on a window sill with a landscape behind it. [Winifred Nicholson] writes about it as a… very specific genre of women’s painting that allowed women to paint a landscape while painting ‘their rightful domain of the still life’. They situate themselves inside and they’re painting a still life, which is what everyone expects of them, but they’re surreptitiously painting the landscape beyond through the window. It’s a slightly subversive act.’

Listen to the full episode to hear more about themes of Virginia Woolf and feminist ideas in art. If you’re interested in viewing the Virginia Woolf exhibition before it closes, it will be at Pallant House Gallery until 16 September 2018. After that, you can find it at The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, from 2 October to 9 December 2018.

Explore more

Art Matters podcast: women artists in the digital age

Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf and the power of sisterhood

How two literary titans made their mark on art

The women artists obscured by their husbands

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes