Download and subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher or TuneIn

Art Matters is the podcast that brings together popular culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

There's a museum dedicated to penises in Iceland and there's an account dedicated to bums in museums on Twitter, but we're turning our attention to representations of vulvas in art with some help from our friends at the newly opened Vagina Museum. The museum was founded in 2017 by Florence Schechter. In the first phase, the museum existed as pop-up exhibitions and events before opening the doors to the location in Camden, London in November 2019 with the help of crowd-funding.

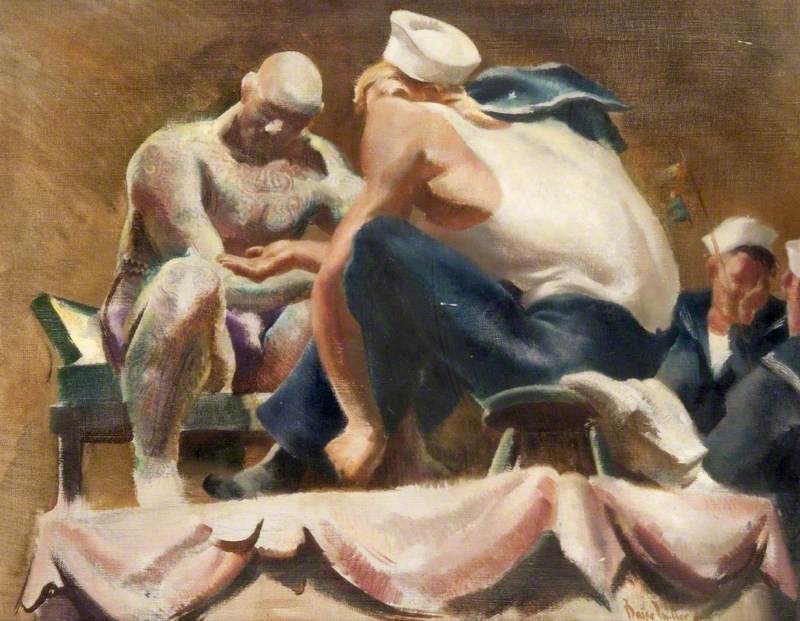

Vagina Reminder

illustration by Charlotte Willcox commissioned by the Vagina Museum

'The main focus of the museum is to educate the general public about the gynaecological anatomy,' says Sarah Creed, Curator of the Vagina Museum. 'In March 2019, the government did a YouGov survey looking at how people could label an anatomical diagram [of female genitalia] ... and 52% of the individuals surveyed couldn't locate the vagina on that diagram. When you split those results by gender, 47% of what the survey classified as women couldn't find the vagina.'

View this post on Instagram

With their first exhibition titled 'Muff Busters', they've decided it was best to start with the basics. There's a perception that we're all taught basic sexual health and anatomy information in school, but Sarah told me that the anecdotal feedback from museum visitors indicates this education varies wildly from school to school, with some visitors saying they weren't taught any sex education at all. With that in mind, before we get into a conversation on art, it may be good to do a little sex education housekeeping upfront.

'When we talk about the vulva, that is essentially the external anatomy – so that is everything that you see on the outside of the female genitalia,' says Sarah. 'The vagina is part of the internal anatomy, so it is a correct terminology for the gynaecological anatomy because it is part of it, but it doesn't encompass the entire gynaecological anatomy.'

The Venus of Willendorf

c.30,000 BC, oolitic limestone by unknown artist

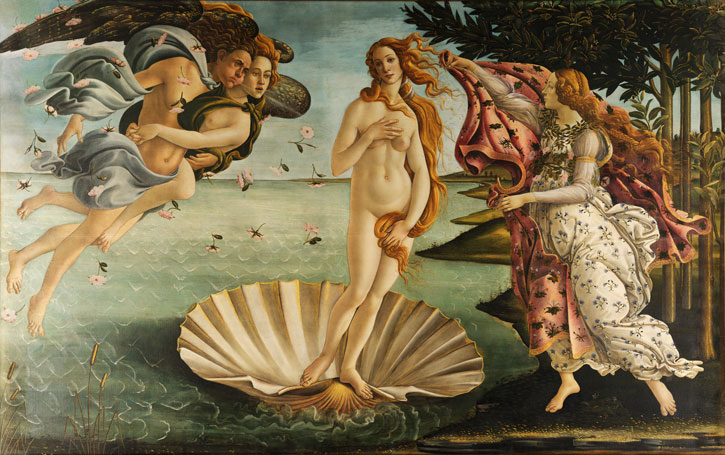

Depictions of vulvas can be found throughout the history of art, with the earliest known examples dating back tens of thousands of years. Venus figurines are some of the oldest works of prehistoric art known to researchers, and the Venus of Hohle Fels is one of the oldest sculptures of a human. Many art history students begin survey classes with one of these small figures as an example – in my class, it was the Venus of Willendorf, which dates to around 30,000 BC. Venuses are often small but shapely figurines with pronounced breasts and vulvas. The head, arms and feet may be minimised by comparison, and the legs often come down to a point. As these pre-date recorded history, researchers can only speculate on their function, but it is believed that they served some ritualistic or symbolic purpose, perhaps relating to fertility.

'Aphrodite Braschi'

(copy after c.350–340 BC votive statue 'Aphrodite of Cnidus'), 1st C BC by unknown artist

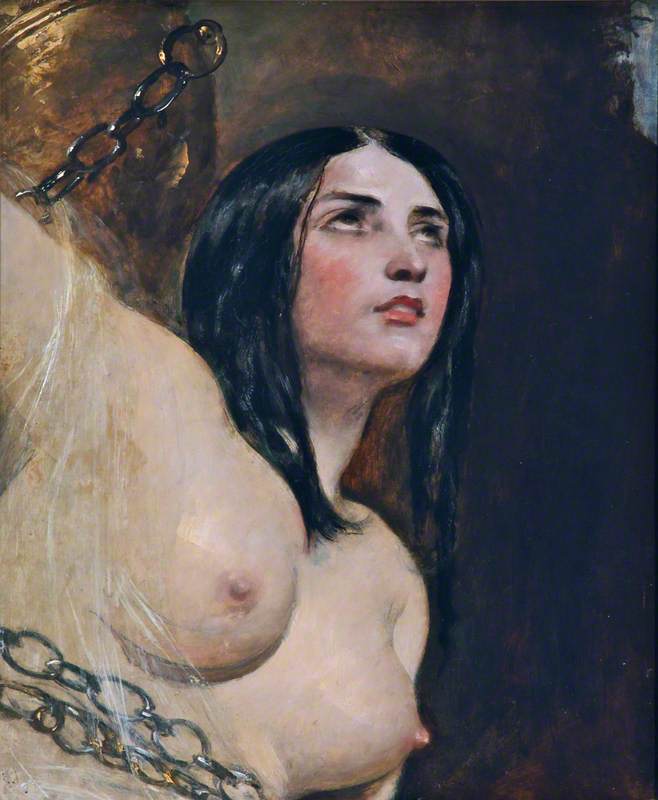

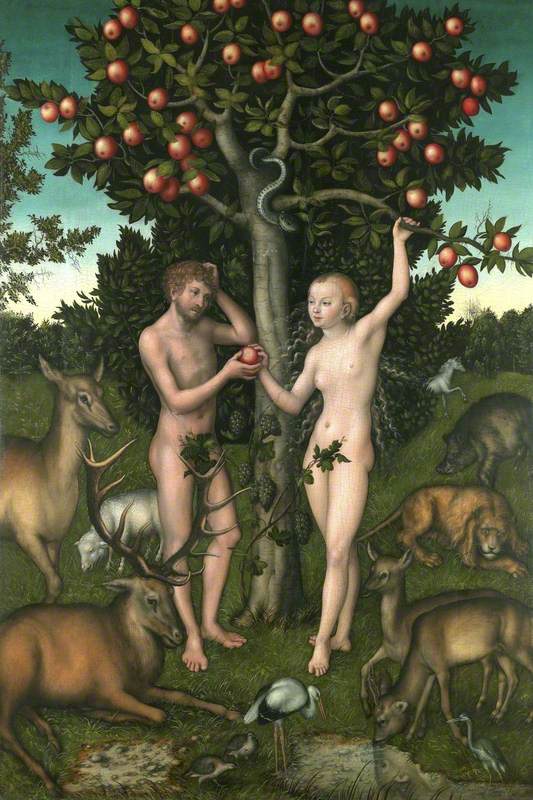

While it is common to find depictions of penises in classical sculpture, vulvas are often covered by strategically placed drapery. Even where a figure is uncovered – as is the case with a sculpture of Aphrodite dating to 350 BC in the Glyptothek collection in Munich – the genital area may be depicted as a nondescript v-shape, with no distinguishable vulva. This is a trend that carried forward through art history as artists began to look back to classical sculpture and mythology for inspiration.

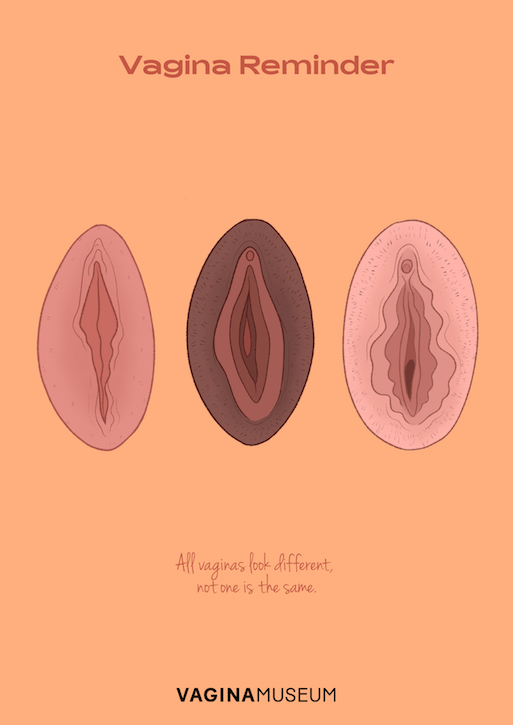

The Birth of Venus

c.1485, tempera on canvas by Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510)

'I think it's a lot to do with the demureness of the woman, historically,' says Sarah. 'Also, people had never really studied [the vulva] or looked at them in great detail. In the way that the traditional artist and sitter worked together, it was quite common for models to be fully nude with artists. It wasn't that the subject matter wasn't there in front of them, but there was this discretion that was made.'

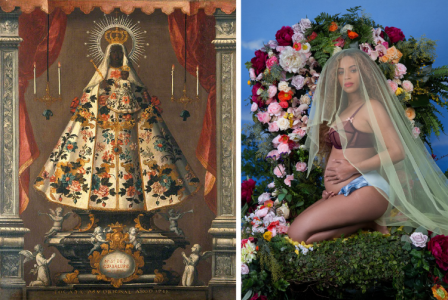

Botticelli's famous painting The Birth of Venus offers a great example of the creative ways an artist would cover the vulva. In this painting we see a fully nude Venus emerging from the ocean on a shell. Venus holds her left hand to her upper thigh, pressing her long red hair over her genitalia. I've always found it fun that Botticelli chose to drape the hair in such a way as to suggest the image of the vulva laying underneath.

In the Manchester Art Gallery collection, there's a painting by John Roddam Spencer Stanhope titled Eve Tempted that uses a similar tactic. A nude Eve reaches for forbidden fruit as a – frankly quite creepy – serpent with a human head whispers to her to take it. Her long hair is draped across her lap and – what do you know – perfectly covers her vulva.

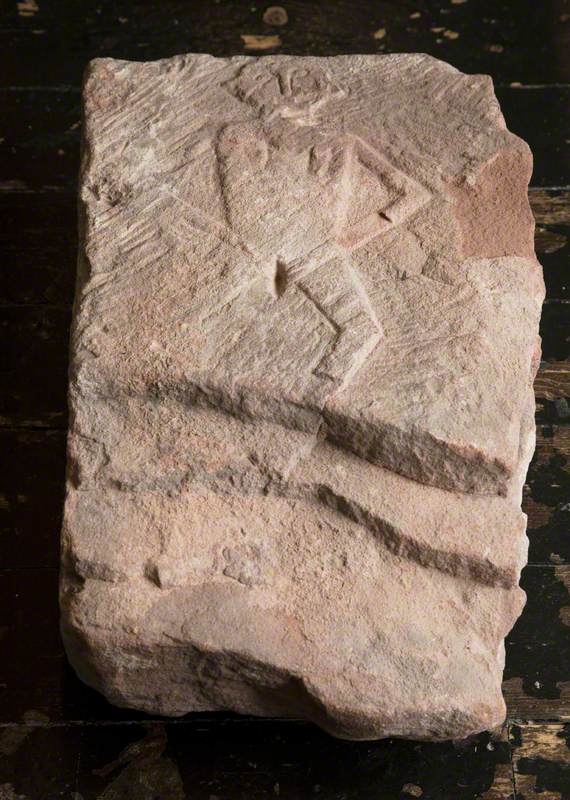

As with the earlier example of Venus figurines, it wasn't always the case that vulvas were treated so discreetly, and they could be found prominently displayed in some pretty surprising places. Sheela-na-gig are architectural carvings of nude figures that prominently display the vulva. They're often found on churches and castles, and are believed to have served a guardian function – not unlike a gargoyle or grotesque. The Vagina Museum have commissioned their own replica of a Sheela-na-gig that helps to preserve the good vibes in their space.

L'Origine du monde (The Origin of the World)

1866, oil on canvas by Gustave Courbet (1819–1877)

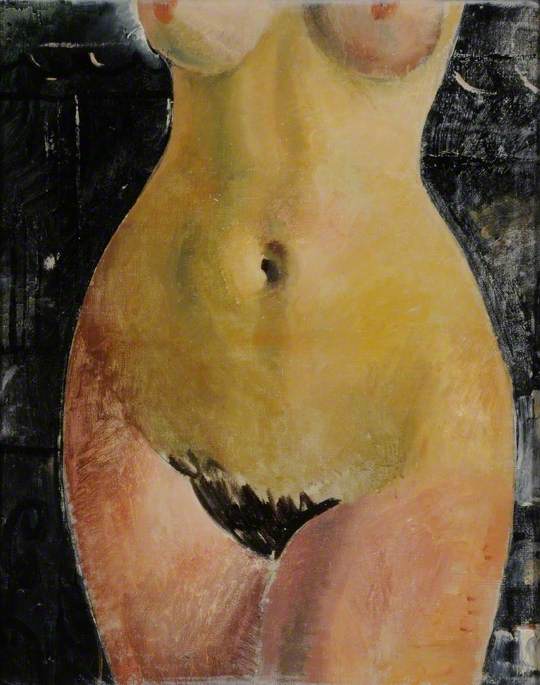

Vulvas in modern and contemporary art

The most notorious depiction of a vulva in art is arguably L'origine du monde (The Origin of the World) by Gustave Courbet. There has been much contention about the commissioner and sitter of this painting. The woman was originally believed to be Courbet's lover, Joanna Hiffernan. This idea was supported by the knowledge that she was also James Abbott McNeill Whistler's lover at one time, and the two men had a disagreement around the time the painting was done. Recent discovery of Courbet's correspondence with Ottoman diplomat Halil Şerif Pasha indicates that Şerif – a playboy of sorts – commissioned the painting of his lover Constance Queniaux, who was a retired ballet dancer in Paris.

The Dinner Party

1974–1979, ceramic, porcelain & textile by Judy Chicago (b.1939)

The Dinner Party

1974–1979, ceramic, porcelain & textile by Judy Chicago (b.1939)

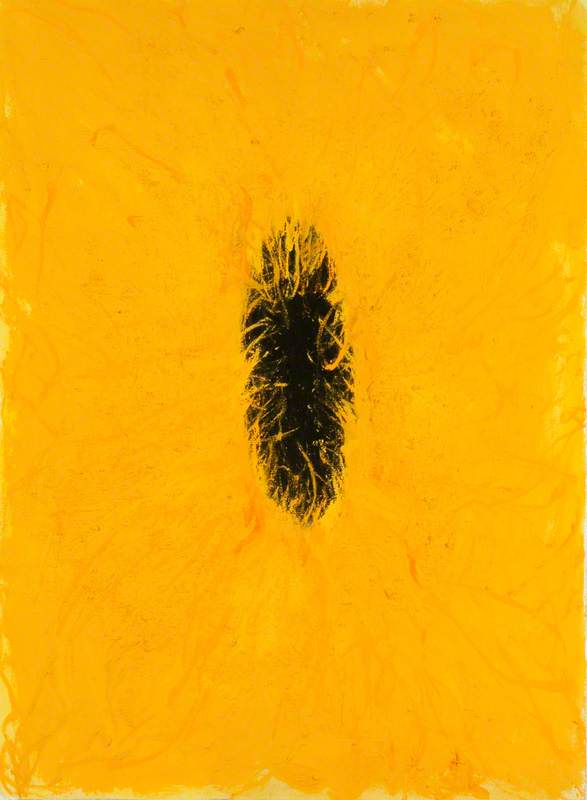

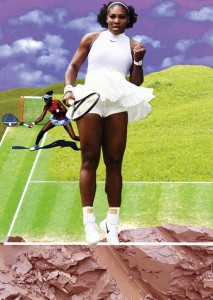

Moving into the twentieth century, we see an increase in depictions of vulvas – particularly from women artists. Judy Chicago's powerful 1979 mixed media work The Dinner Party is one prominent example. The installation is a feminist celebration of 39 women who made important contributions to art and society. The table is arranged in a triangle and each place setting is different, with a small table runner embroidered with a woman's name and ornate plates in the shape of vulvas. The imaginary dinner party includes historical figures like Hatshepsut and Sojourner Truth, and also fellow artist Georgia O'Keeffe.

'The reason [Georgia O'Keeffe] was given the place setting was largely because of her floral paintings which have had all of this speculation about whether or not she was depicting vulvas,' says Sarah. '[O'Keeffe] really denied this and said it was a Freudian interpretation of her paintings.'

One of the great things about the Vagina Museum is their educational and inclusive approach. In the 'Muff Busters' exhibition, they educate visitors on anatomical terms and sexual health, but also on the difference between sex and gender.

'A big ethos of ours as a museum is also not defining individuals by their anatomy. So we are a transgender and intersex ally as an organisation,' says Sarah. 'Not all women have a vagina and, indeed, not everyone with a vagina or a vulva identifies themselves as a woman. I think it's really important to have individuals who identify as male or female or any gender of their choice – or non-binary even – engaging with it as a subject matter.'

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes