Art Matters is the podcast that brings together pop culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

Download and subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher or TuneIn

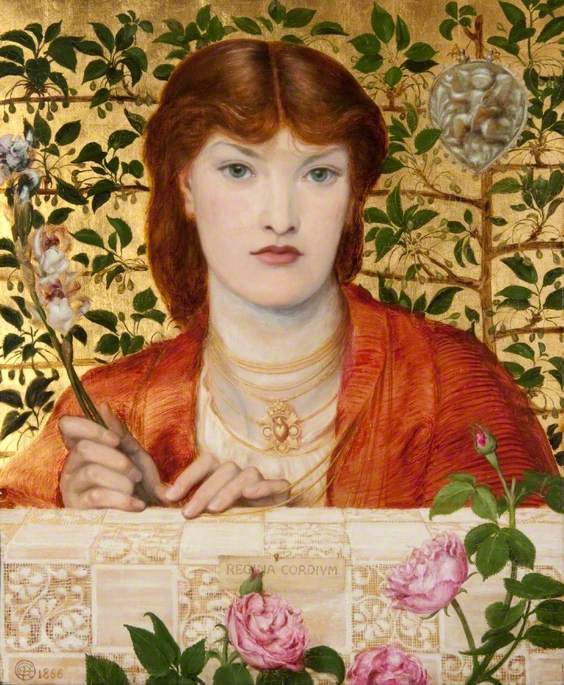

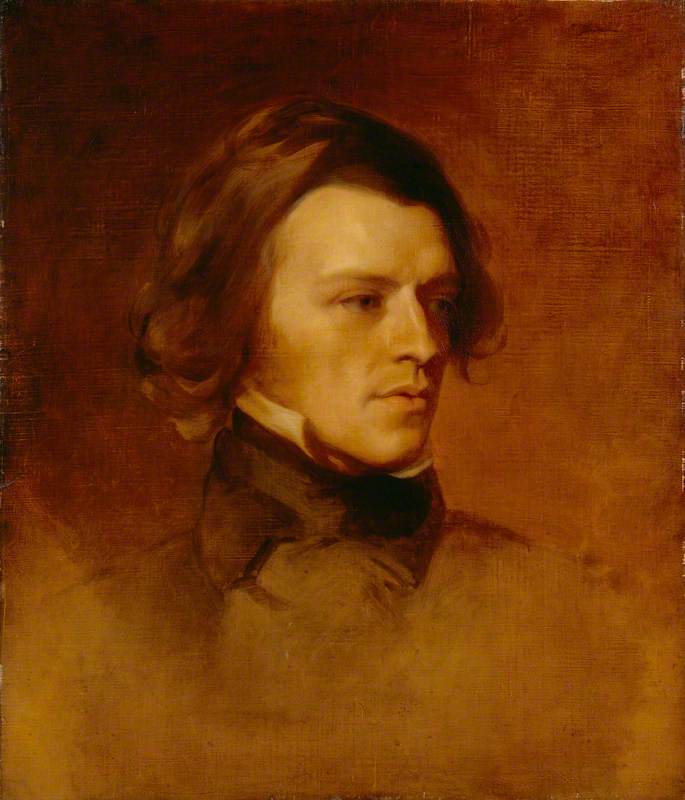

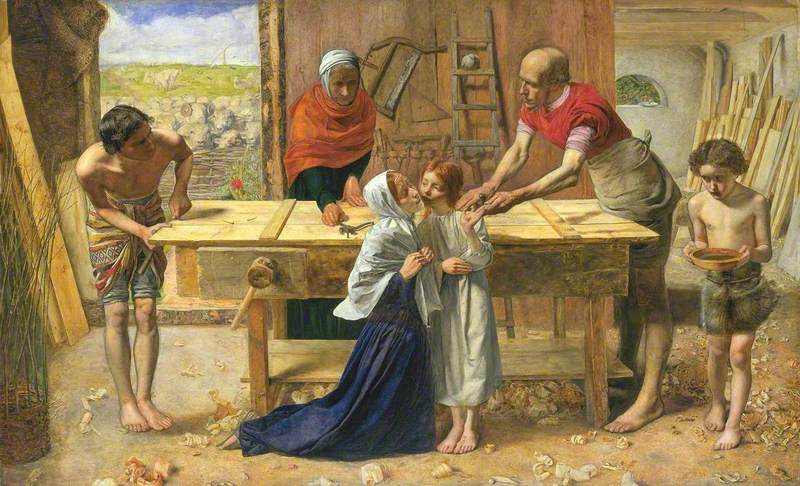

Art rebels of their day, The Pre-Raphaelites were a collection of artists, writers and critics with a shared vision for their realist approach to art. Founded in 1848, their name stems from their rejection of the ideas promoted by the Royal Academy, at the time, of painting in the classical style of Raphael. They preferred the earlier Italian Renaissance style of artists from the quattrocento (the Italian name for the 1400s), who in the timeline of art history were – you guessed it – pre-Raphael.

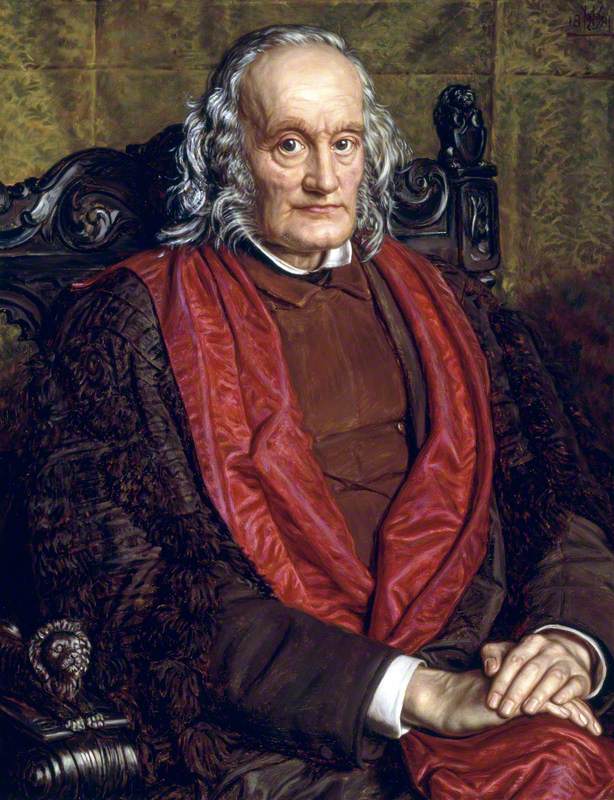

The group weren’t only using art as a tool of expression. They had a lot to say and briefly produced a magazine to convey their ideas. John Holmes is a Professor of Victorian Literature and Culture who wrote The Pre-Raphaelites and Science, a book exploring the relationship the brotherhood had with scientific ways of thinking. He first became interested in this connection after teaching lessons on the Pre-Raphaelites’ short-lived journal, The Germ (interestingly, a scientific term for its name). Though it only produced four issues, John tells me that each one consistently wrote about the relationship between art and science.

The clues for their interrelationship with science are there if you know where to look. For example, the idea of speaking ‘truth to nature’ was a principle John Ruskin argued was an artist’s central purpose. ‘Ruskin was the leading art critic of the 1840s and 1850s, and he became a little bit of a mentor to Pre-Raphaelites,’ says John Holmes. ‘His ideas about truth to nature were similar to [the Pre-Raphaelites], but not exactly the same. They both felt that art should reflect what the painter sees. You shouldn’t presume that art should copy or imitate the practices of previous artists. Instead, there was a duty on the artist to look at what he or she saw in front of them and paint it with that truth, that accuracy, that precision.’

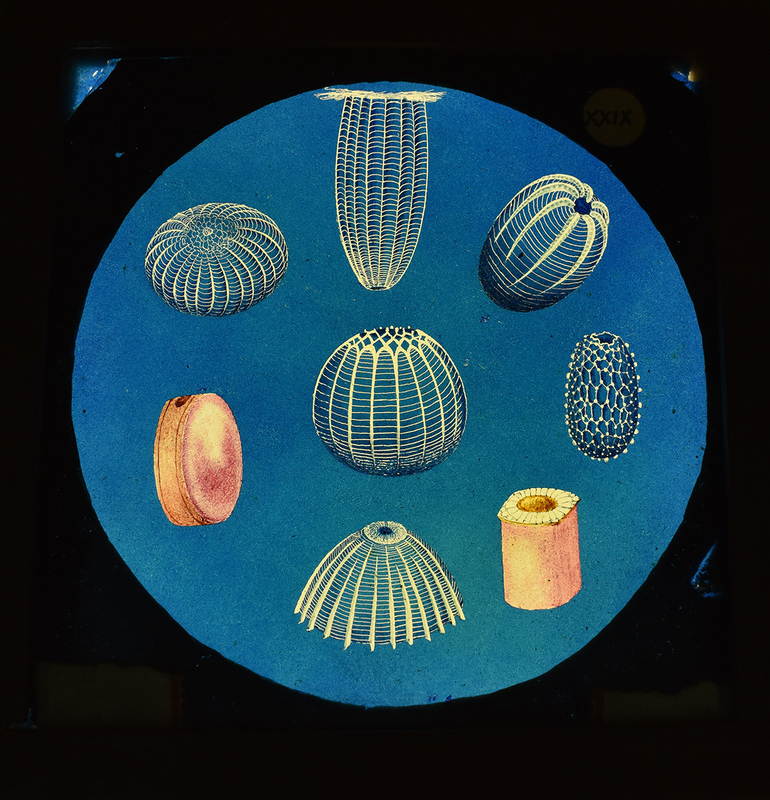

A desire to portray things realistically does have a scientific ring to it, but I was curious how much of an active role science played in Pre-Raphaelite thinking. Was it a small part of their ethos or was it central to their work?

‘[Frederic George Stephens] articulated very clearly in The Germ that, first of all, the artist’s standard of observation had to match that of a scientist,’ says John. ‘Secondly, for Stephens science was something that was very progressive... His view was that art, too, could progress in its own sphere morally and in its precision, truth and accuracy if it imitated the sciences.’

The art critics in the collective clearly laid out their ideas about the importance of scientific thinking, so if we consider this while viewing Pre-Raphaelite works, they take on new meaning.

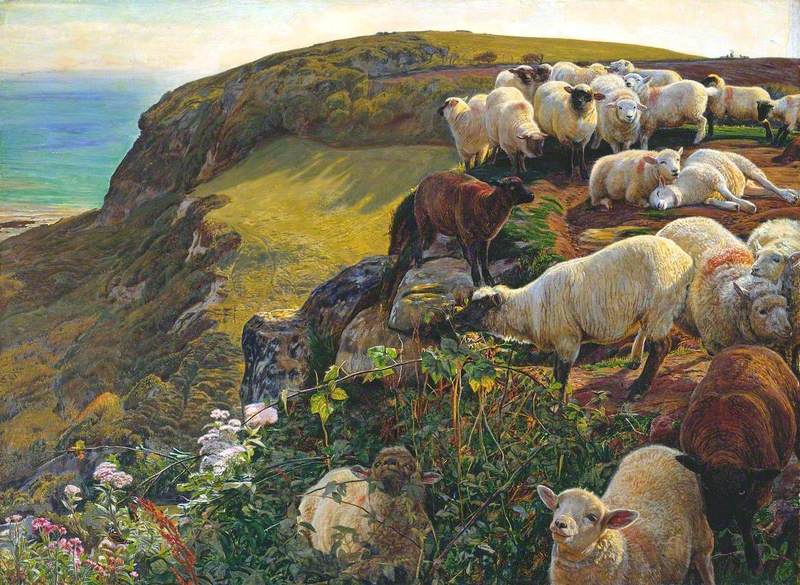

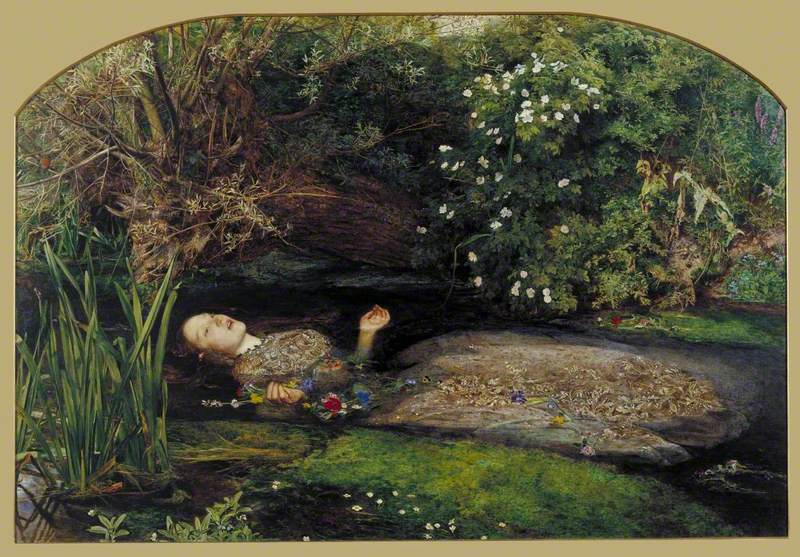

Using one of the most popular paintings by John Everett Millais as an example, Ophelia offers insight into the collective’s scientific approach to art. Millais painted the scene en plein air for months to capture the environment accurately. ‘You’ve got two things going on,’ says John. ‘You’ve got science on the model of natural history – and that’s one of the things that recurs in their painting, particularly the landscape painting of Pre-Raphaelitism – but you’ve also got an active experiment... The experiment is what can art achieve through painting directly onto canvas in the open air, in a particular location over a period of time?’ The artists and even the models went to great lengths for the integrity of these experiments. Elizabeth Siddal, who modelled for Ophelia, became ill after sitting in a cold bath for hours so that Millais could accurately capture the effect of a woman floating in water.

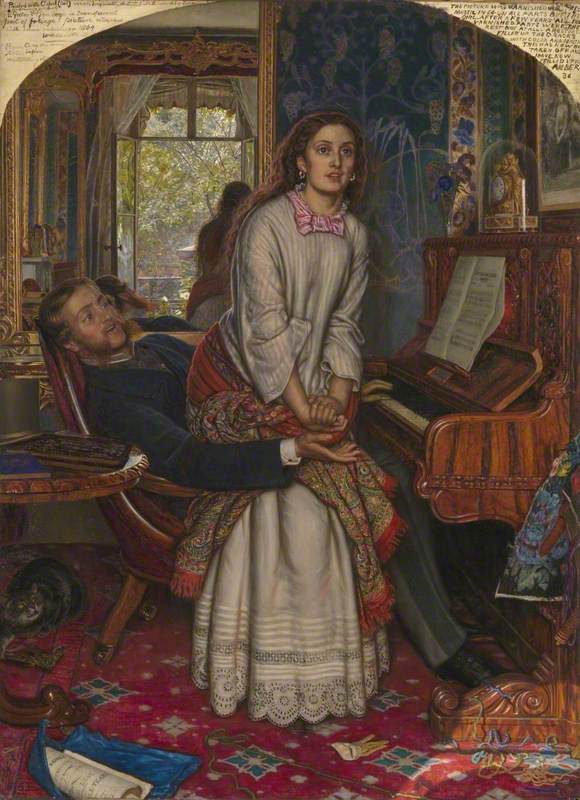

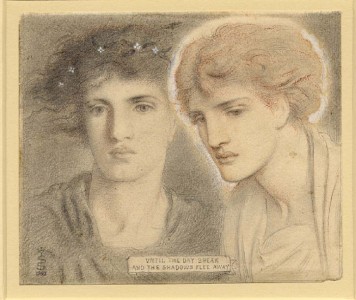

The Pre-Raphaelites weren’t just exploring natural sciences: they also had views on psychology, which at the time was deemed a slightly dubious branch of science. They believed that an artist could gain a better understanding of psychology through their practice than some of the questionable methods employed in this period (e.g. measuring a patient’s head). One way of exploring this was through the depiction of the dynamics between figures in a painting.

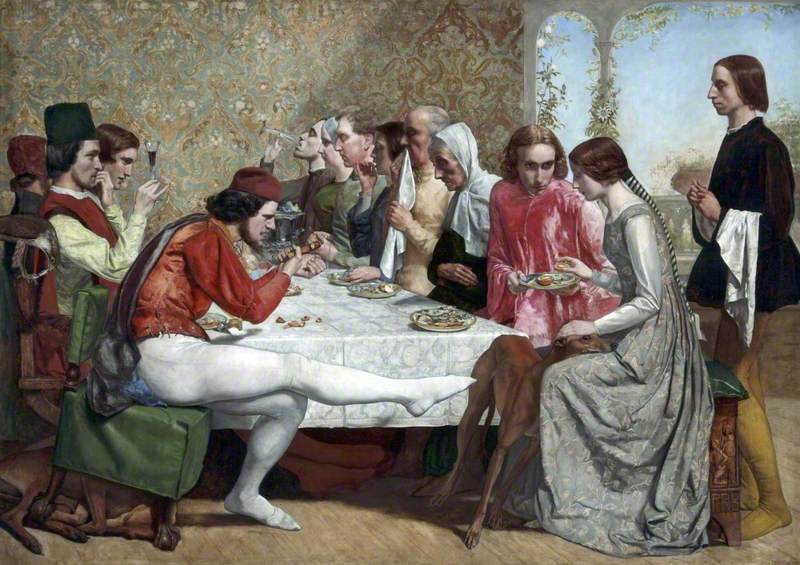

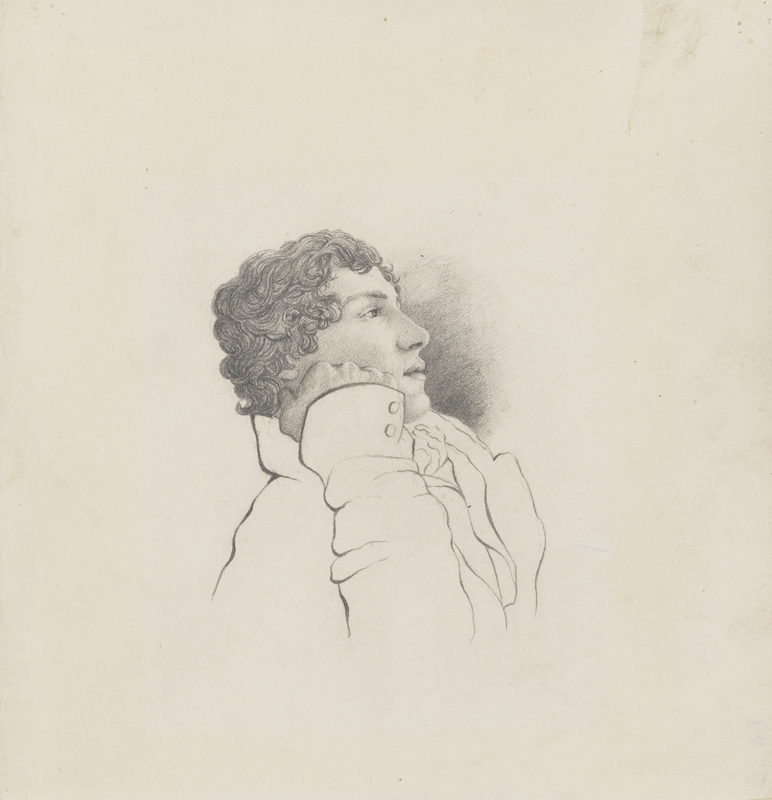

Looking at Millais’ Isabella, one can observe the underlying subtleties between the characters, where we see two brothers on the left displeased with their sister falling in love with a servant, seated to the right. This is a scene from the story Isabella, or the Pot of Basil, and proceeds the brothers murdering their sister’s lover. The artist went through several sketches of this work to land on this final version that gently communicates the internal thoughts of the players involved; it’s certainly a form of experimentation.

We can see the Pre-Raphaelites were carrying out their own art ‘experiments’ in the name of science, but the relationship with science was reciprocal. There were a number of scientists that valued their thoughts and became allies in their mission. While some of their fellow artists rejected their theories, important scientific figures of the day, like Sir Richard Owen, embraced them.

‘There was a lot of respect for what they were doing,’ says John. ‘Scientists recognised that these were people that were trying to give art a new and serious programme through practices that the scientists could recognise.’ Through their relationship the scientific community, Pre-Raphaelite members were asked to consult on the building of the new Oxford University Museum of Natural History, and the decoration of the museum was based on Pre-Raphaelite principles of accuracy and attention to detail.

You can hear a fuller explanation of the Pre-Raphaelites’ relationship with science in the episode above. If you want to discover more, you can pick up John’s fantastic book, The Pre-Raphaelites and Science, which goes into even greater detail in this subject.

Explore more

L. S. Lowry and the Pre-Raphaelites

Reflections: Jan van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites

Witches: the Pre-Raphaelite femme fatale

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes