Art Matters is the podcast that brings together pop culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

Download and subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher or TuneIn

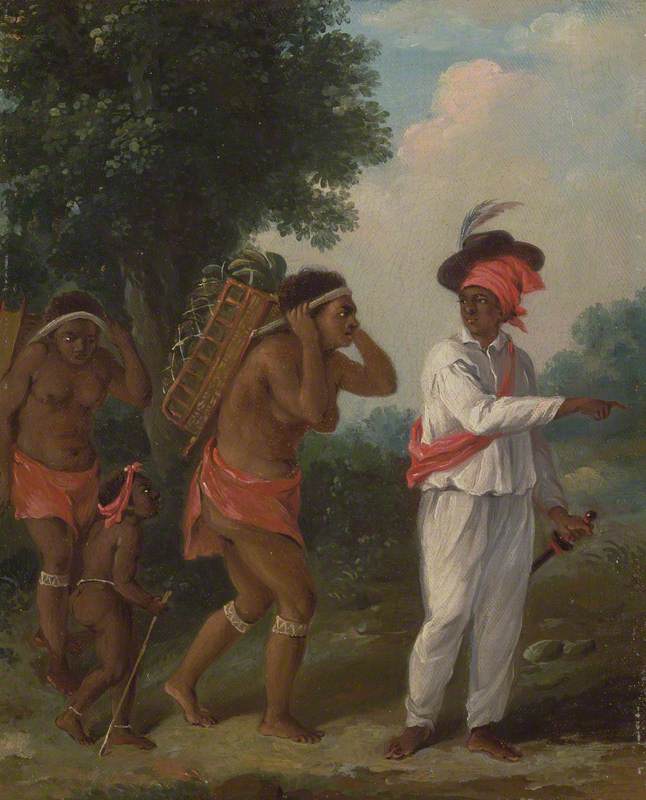

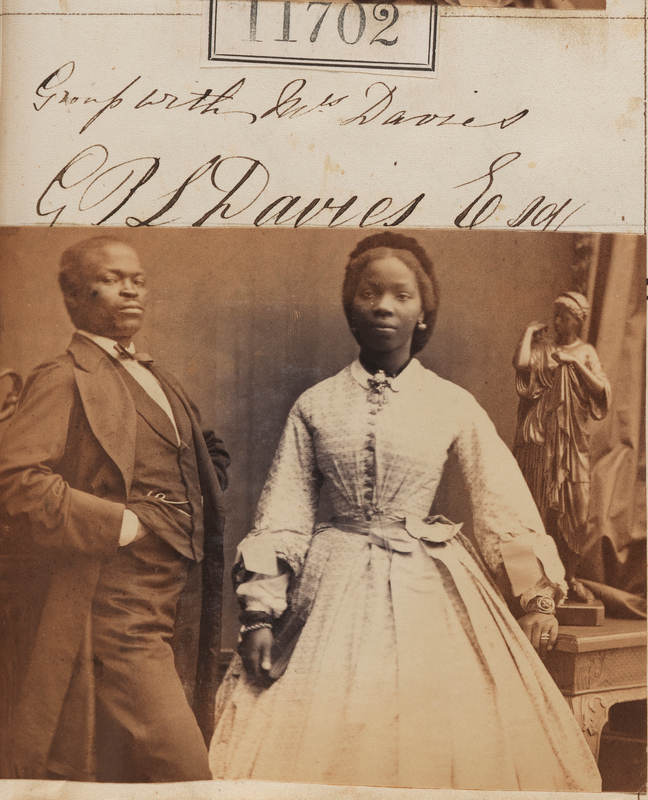

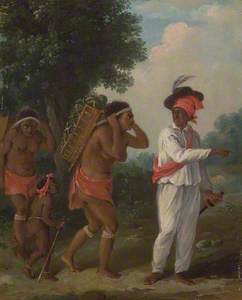

More and more, museums are working towards facilitating experiences that provide inclusive interpretations of their collections. One of the ways this is done is through themed tours, which can provide an insightful way of helping visitors connect with collections that many audiences often feel removed from. Cultural historian Michael Ohajuru runs one such tour called The Image of the Black in London Galleries. Through the tour, Michael explains the changing presence of black figures in European painting as a journey.

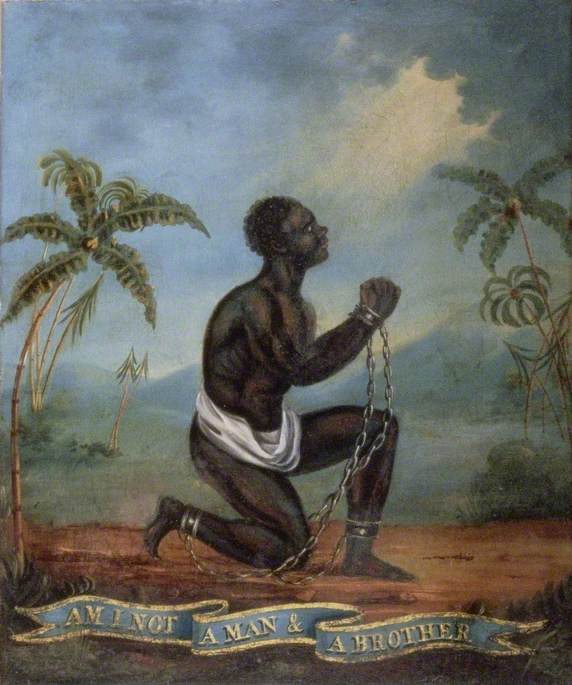

'At the start of the journey, I talk about the black [figure] as a subject or object of economic capital – a slave or a servant,' says Michael. 'By the end of the journey, they're creators of cultural capital. They're artists in their own right, creating an expression of themselves the times through their art.'

Michael breaks this evolution down further into two categories of works: ones with an explicit or implicit presence of black figures. We'll come back to what 'implicit' means, but let's first look at some explicit examples – that is to say, works of art that overtly (or explicitly) include black figures within them.

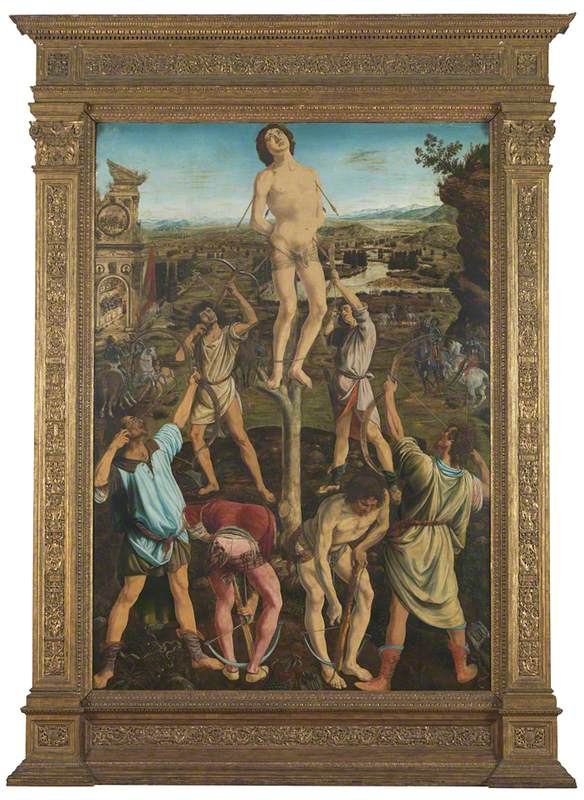

The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian

completed 1475

Antonio del Pollaiuolo (c.1432–1498) and Piero del Pollaiuolo (c.1441–before 1496)

The explicit presence

The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian by Piero del Pollaiuolo and Antonio del Pollaiuolo is a famous altarpiece originally painted for the Pucci family of Florence. The patronage is important to note because the heads of two black men can be seen depicted on the triumphal arch at the top-left side of the painting. The image of a Moor's head was first adopted by an early Pucci ancestor, Jacopo Saracini, and became an emblem for the family.

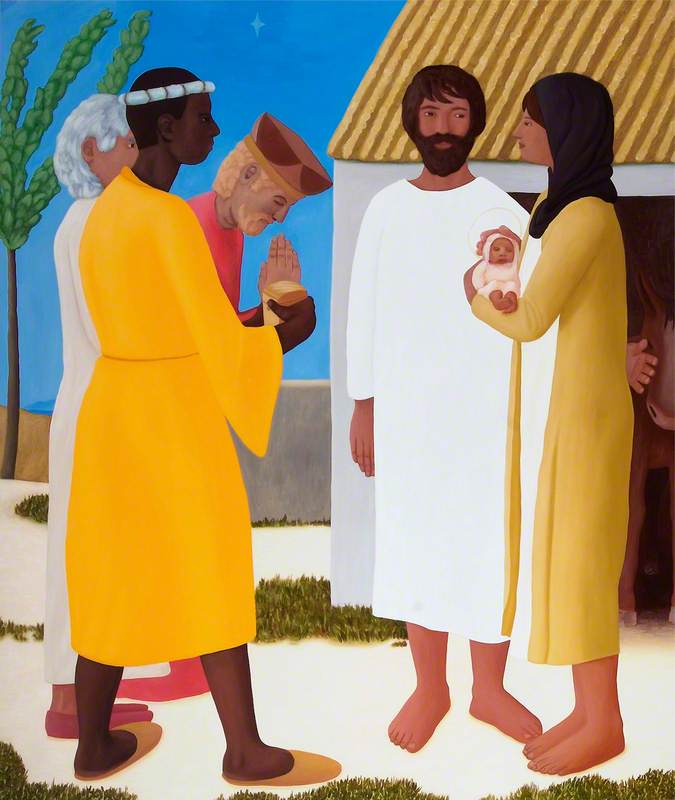

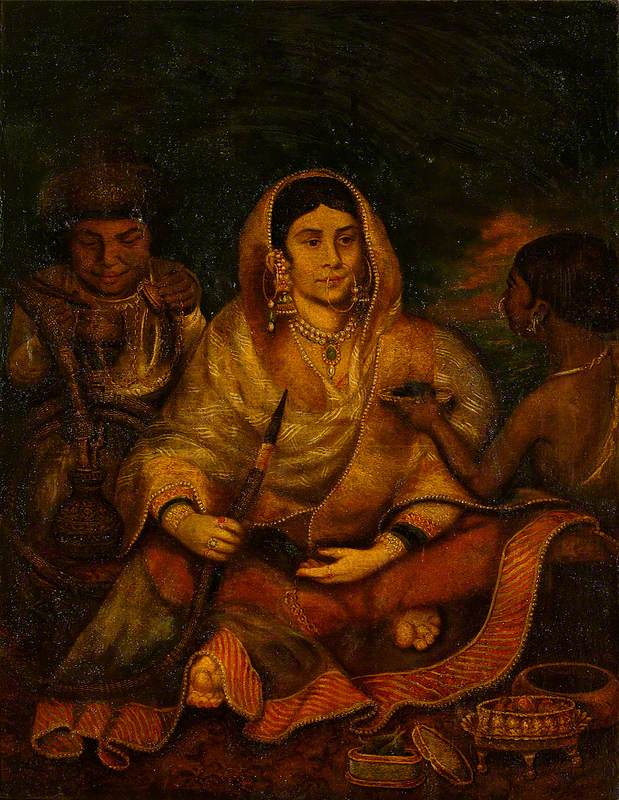

A popular painting theme that more prominently includes a black figure is the Adoration of the Magi. This is a scene from the Nativity story wherein the infant Christ is visited by three Magi, or kings, bearing gifts. In an example by Paolo Veronese in The National Gallery, we see the black king at the far left of the canvas, leaning in the opposite direction to the diagonal composition of the other attendees.

'The black king is always the last in line, he's dressed a little differently – often exotically,' says Michael. 'He's not quite part of the three [kings] – it's two and one ... This is a semblance of creating an other.'

As a last example of explicit representations of black figures, let's examine Titian's Diana and Actaeon. The story is taken from the poem Metamorphoses by the Roman poet Ovid. In it, Actaeon comes across Diana, goddess of hunting, while she is bathing. Her attendants attempt to quickly cover her and, in the process, Actaeon is splashed with water that turns him into a stag. To the far right of Titian's painting, we see a black servant tending to Diana.

'People have written about the fact that [the inclusion of a black woman next to Diana] is a play on the goddess of fate, Fortuna. Fortuna is two-faced – half of her face is white, half of her face is black,' says Michael. 'Some people argue that Titian is trying to have Diana as the goddess of fate and he's using the black figure to symbolise her. There are little clues in the painting. It's actually on a slope, and Fortuna lives in a house on a slope ... It's all about Actaeon meeting his fate.'

The implicit presence

The implicit presence of a black figure is one in which that figure should be there and is not, or is one in which their presence is implied through some other subtext. A simple example of this is Mrs Oswald by Johann Zoffany. It shows a wealthy woman seated outside in her finery. The Oswald family's wealth was acquired through the slave trade. Mrs Oswald's clothes and, indeed, the painting itself were funded through selling slaves and slave labour. The painting doesn't explicitly include a black figure, but the story of the black presence in Europe is embedded in the subtext of the work.

Seaport with the Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba

1648

Claude Lorrain (1604–1682)

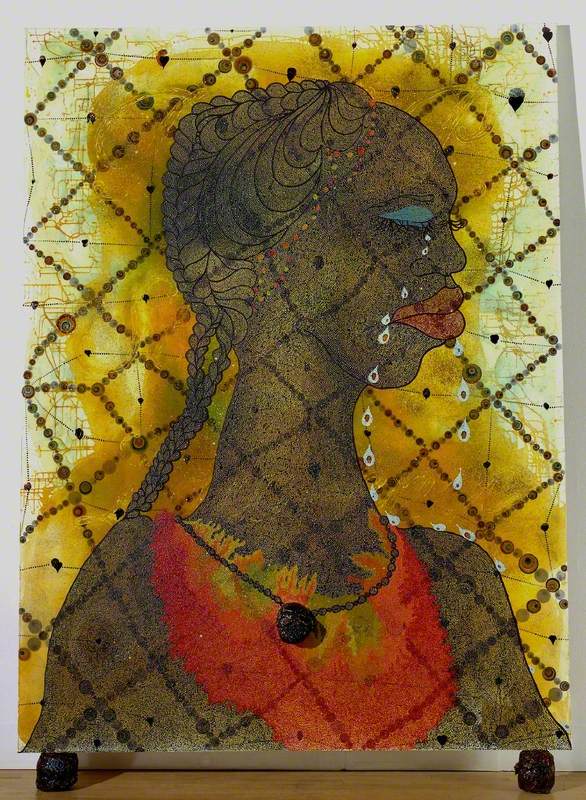

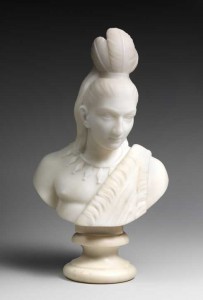

As a different form of implicit presence, paintings of the legendary Queen of Sheba offer an example of artworks where a black figure could or should be present, but isn't. Though she hails from the same place as the king in the Adoration story, her black identity is not preserved in the same way and she is often represented as a white woman.

'In the white Queen of Sheba, you see misogynoir in action. You see the dual runway of racism and sexism. Sexism because the Queen of Sheba eventually gets sexualised and no longer becomes a suitable image for any woman,' says Michael. 'The woman is seen as not being a suitable role model, but then she can't be black because [they didn't want to] express beauty in blackness.'

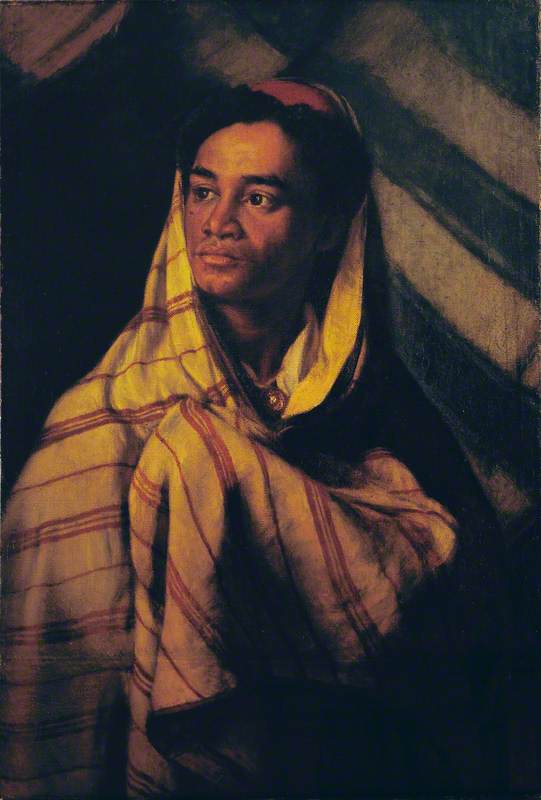

Juan de Pareja (1606–1670)

1650, oil on canvas by Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

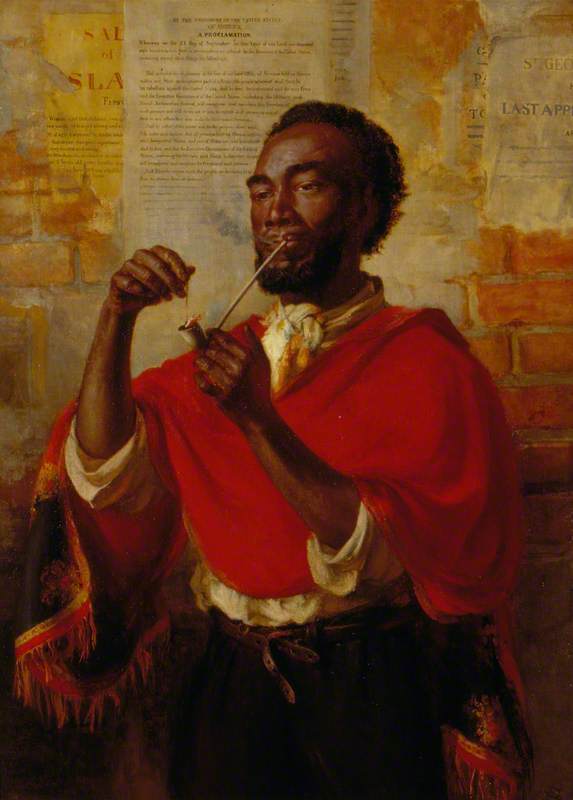

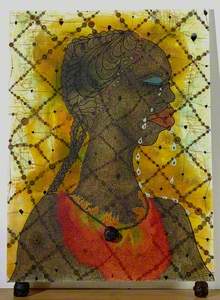

Black artists in Europe

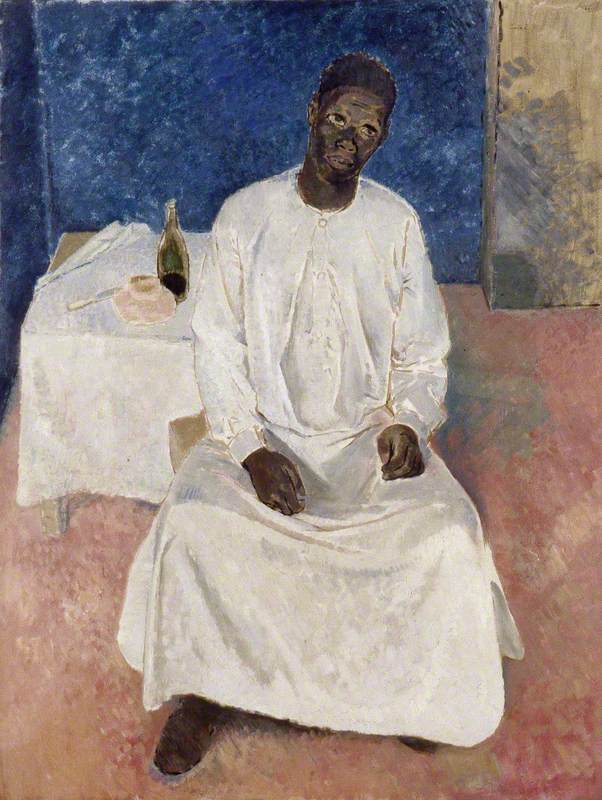

Moving forward through European history, the narrative of the black figure in art evolves as we begin to see black artists. With this, artists could reclaim ownership of their own identities and manner of representation. Michael cites the earliest example of a black artist of note as Juan de Pareja (1606–1670), who was Diego Velázquez's slave and painting assistant. Velázquez later freed Pareja, after which point he worked as an artist in Madrid.

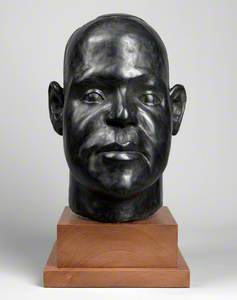

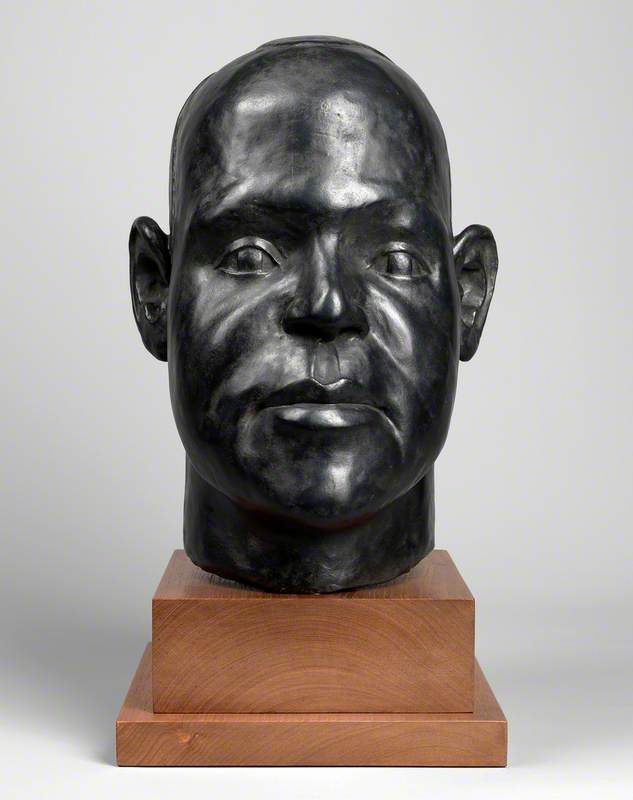

Harold Moody (1882–1947)

(based on a work from 1946) 1997

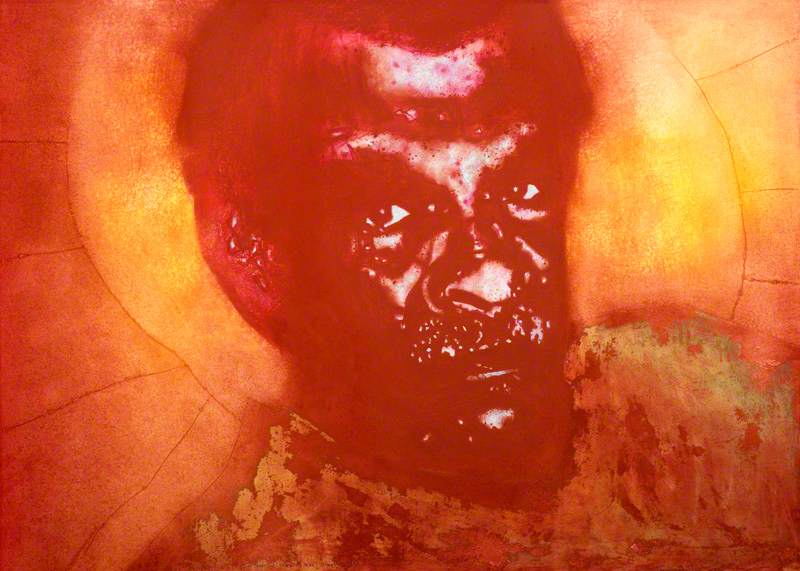

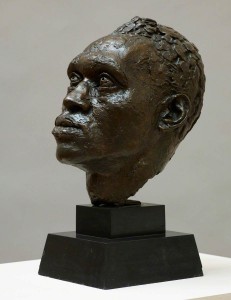

Ronald Moody (1900–1984)

Centuries later followed sculptor Ronald Moody. Born in Jamaica, Moody moved to London to study dentistry before falling in love with art after a trip to the British Museum. His career gained traction in Paris, where he exhibited work before having to flee the Nazis in 1940. After returning to London, he continued to produce sculptures, including a bronze bust of his brother Harold Moody, which is now part of the National Portrait Gallery collection. Harold was notable in his own right, becoming a celebrated physician and civil rights activist.

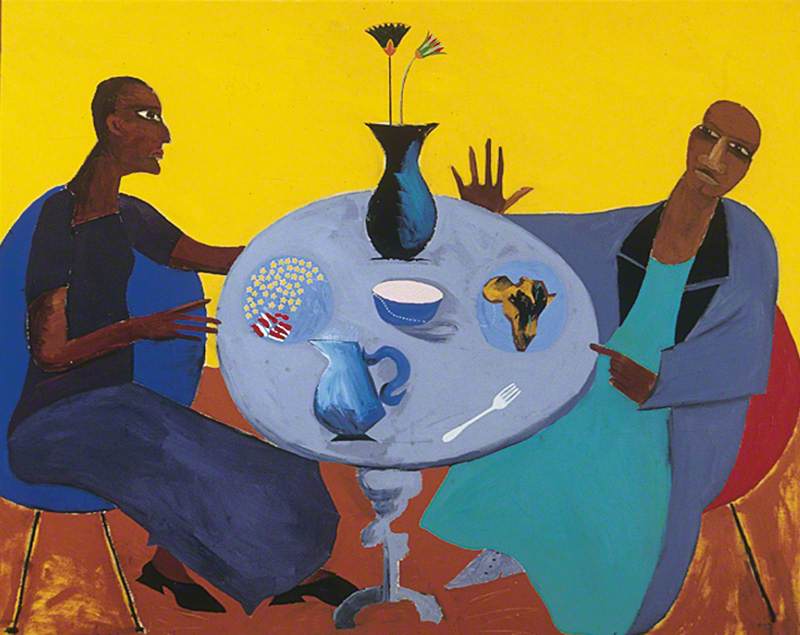

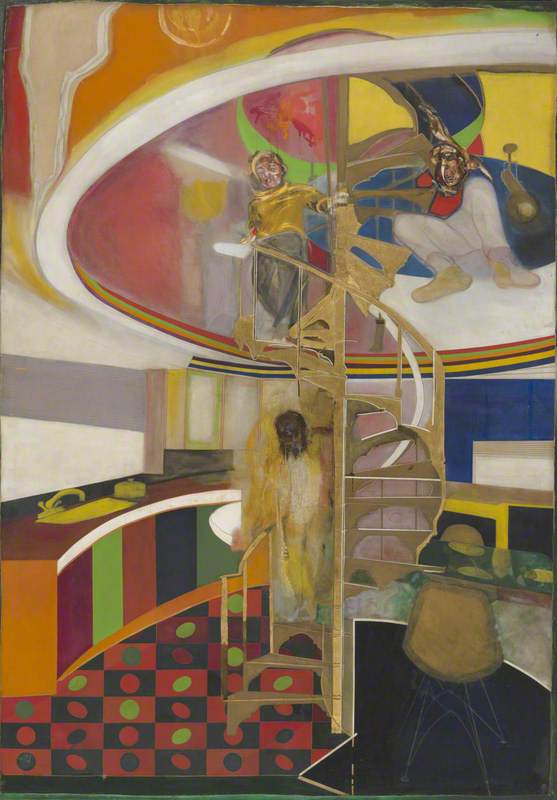

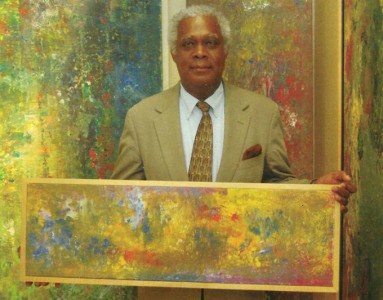

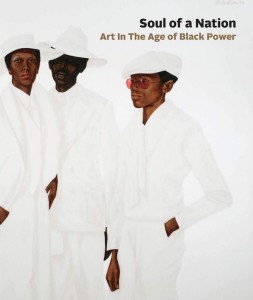

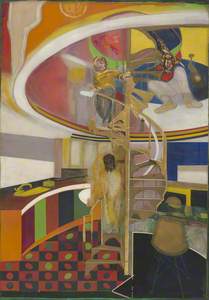

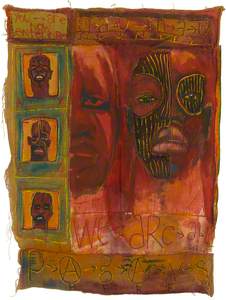

Guyana-born artist Frank Bowling was born around the time Moody's career was hitting its stride. He moved to London at age 19 and earned a scholarship to the Royal College of Art. He was initially told by a gallerist that Britain wasn't ready for a black artist but, after a stint in the United States, he returned to have a long and successful career in the UK. There was recently a retrospective of his 60-year career at Tate Britain.

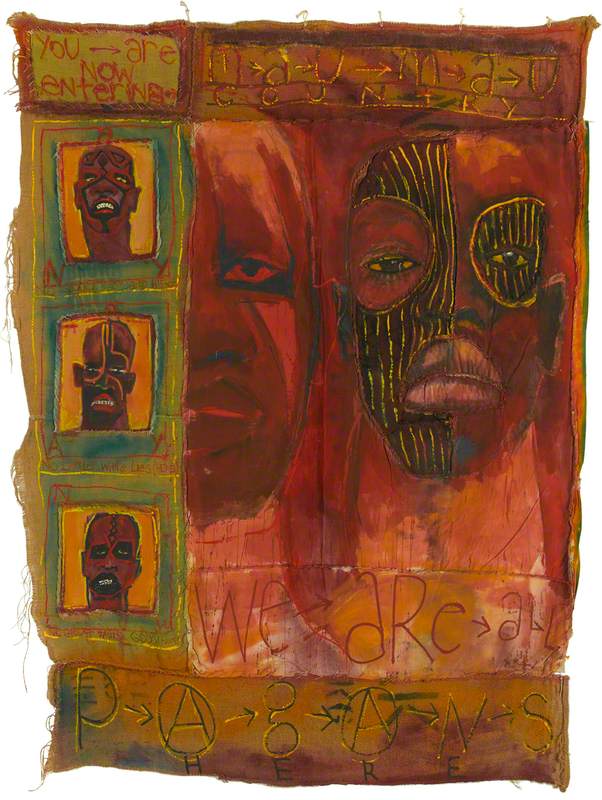

The number of black artists increased exponentially in the twentieth century, seeing the rise of artists like Lubaina Himid, Chris Ofili, Keith Piper and others. Some of these artists directly tackle issues surrounding racial identity in their work and some don't, and the freedom to do either is imperative.

'We've come from being the subjects of economic capital and symbolism, through to actually creating cultural capital that people value,' says Michael. 'Works that people value because they reflect our times and they say something to us through their work.'

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes