Download and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or TuneIn

Art Matters is the podcast that brings together popular culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

Tarot has origins in playing cards, which were first invented in China in the ninth century. From there, card games spread across Persia, Egypt and into Europe. It was in fifteenth-century Italy that we have the first documented evidence of what we now know as tarot.

'The aristocracy decided to add an extra suit [of cards] with very vivid pictures and allegorical images... and that suit in the game would trump the other cards. Trump means triumph – the original name for the tarot was trionfi, or triumph,' says author and tarot expert Rachel Pollack. 'It didn't become known as an occult system until the late eighteenth century.'

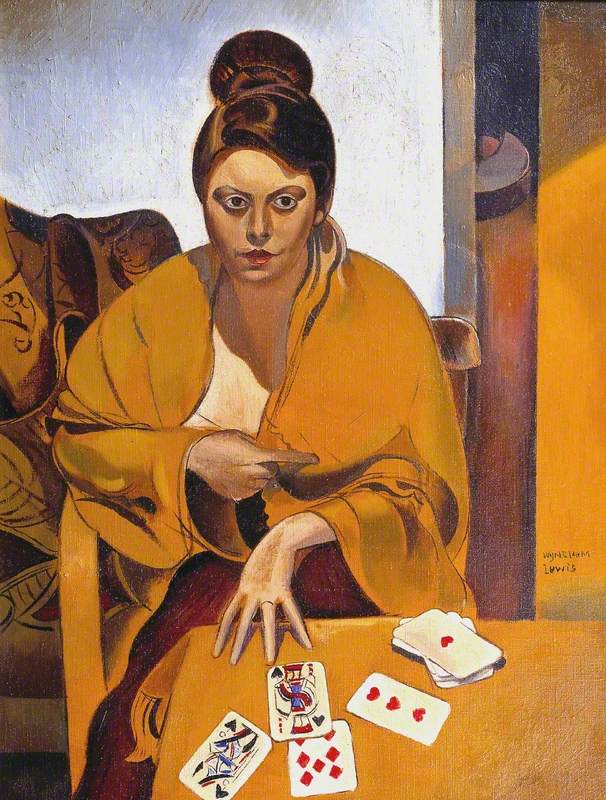

Card-playing and fortune-telling became popular subjects in Flemish paintings and eventually gained traction in sixteenth-century Rome via the work of Caravaggio. In particular, his paintings The Fortune Teller and The Cardsharps helped to grow his budding reputation. Later on, we can see several nineteenth-century examples of genre paintings showing cards being used for divination. Several examples on Art UK feature a woman card reader and only one example I found in the Tate collection includes a man among the sitters.

The Fortune-Teller (The Wise Old Woman)

1891

Henry Meynell Rheam (1859–1920)

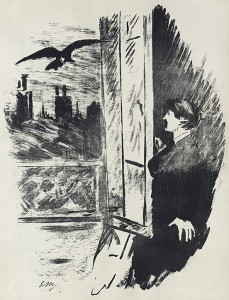

A watercolour by Henry Meynell Rheam in the Penlee House Gallery & Museum collection shows three women gathered around cards spread on the floor. The eldest of the three appears to be reading the fortune of the woman seated across from her. Behind the fortune-teller are a black cat and a raven – symbols often connected with magic.

Once the cards became associated with occult ancient Egyptian origins, people began to use the cards for other purposes. A fortune-teller named Etteilla helped to popularise tarot with broader audiences in the 1780s, and developed what are known today as the Major and Minor Arcana cards in the tarot deck – 'arcana' being Latin for 'secrets'.

'The Major Arcana are those 22 extra cards – the extra trump card suit – and there's an unnumbered card called the Fool,' says Rachel. 'Then the four suits [of the Minor Arcana] are called wands, cups, swords and, in the modern usage, pentacles, and in the old usage, coins. Those suits consist of numbered cards – ace through ten – and the four court cards – page, knight, queen and king.'

One modern tarot theory is that the Major Arcana cards tell a story beginning with the Fool and ending with the World. It is sometimes referred to as the Fool's Journey, showing the progress of the fool as he or she moves through life. The Fool card can represent new beginnings and open-mindedness. Moving up the numbers of the Major Arcana cards, you conclude with the World card, which can represent accomplishment or fulfilment.

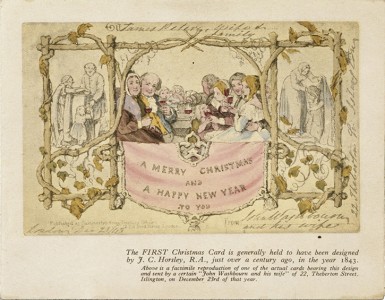

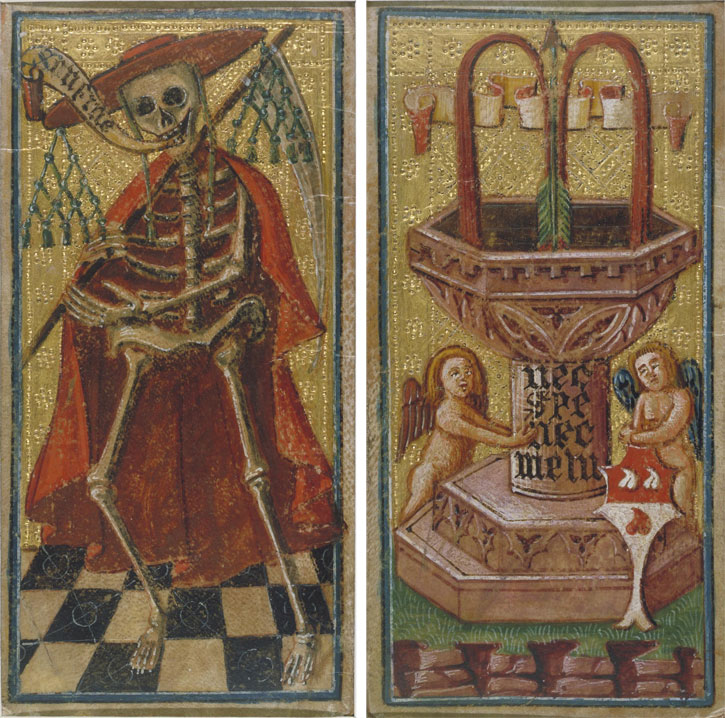

Death and Ace of Cups

1490s, hand-painted tarocco (tarot) cards by Antonio Cicognara (active 1480–1500)

These ideas lend themselves to rich imagery, and early hand-painted decks could be ornate with vivid colours and gold accents. The V&A has a small selection of cards by Antonio Cicognara in their collection dating to the 1490s – it's a good example of the elaborate detail that went into some deck designs.

The Popess card from the so-called Visconti-Sforza tarot deck

c.1450, drawn by Bonifacio Bembo, The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York City

'These were painted very beautifully. The most well-known early decks were two by a man named Bonifacio Bembo, painted around 1450,' says Rachel. 'Both were for the Visconti family of Milan, and the Viscontis were the ruling family of Milan.'

The Visconti-Sforza tarot decks are some of the most complete early examples and they are split across collections around the world. Notably, the decks are missing two particular cards: the Tower and Devil cards. These are two of the more negative cards one can draw in a reading and there's some speculation about why they may be missing.

'Some people say that because they were scary images, they were not proper for ladies of the court to be using. It's more likely that they just were never there,' says Rachel.

Luna (Moon) from the E-Series (Ten Firmaments) tarocchi

c.1465, engraving with gilding by the Master of the E-Series tarocchi

In Giorgio Vasari's series The Lives of Artists, he wrote that Italian Renaissance painter Andrea Mantegna made a set of triumph card prints. This possibly led to a double misattribution of a fifteenth-century deck known as the Mantegna Tarocchi, which are now believed not to have been produced by the artist and not to be tarot cards. Though there is an overlap in some imagery such as the knight, Pope, sun, moon and other themes, the Mantegna Tarocchi are now believed to be instructional cards teaching astrology, mythology and other subjects. They seemed to hold some creative influence as artists including Albrecht Dürer made copies of this deck.

The prevailing pattern for tarot cards began with the Tarot of Marseille, which was developed after the cards became popular in France. The earliest surviving deck by Jean Noblet dates to the 1650s and is less decorative than some of its Italian ancestors. This effectively set the standard for the style of cards we know today – it's in these decks, for example, that we begin to see the titles of cards written on the front. Once there began to be occult meanings attached to the deck in the 1780s, new imagery was introduced to tarot iconography.

Cards from the Rider-Waite deck illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith

'The biggest shift that happened was in 1909 with the publication of a book called The Pictorial Key to the Tarot, and the images in that deck were drawn by a woman named Pamela Colman Smith. She was drawing under the direction of Arthur Edward Waite, who wrote the book,' says Rachel. 'Then the next year they published a deck together. The deck was published by a company called Rider and that deck is now the most famous deck in the world. It's often called Rider-Waite, Rider-Waite-Smith or just Rider Tarot. In that deck, Waite kept to the Marseille images, but he shifted them enough that it really was dramatically different.'

Pamela Colman Smith was born in London to American parents before living a portion of her childhood in Jamaica. She studied art at the Pratt Institute in New York before returning to London, where she worked as an illustrator. Eventually Smith came to be in the circle of Georgia O'Keeffe and her husband Alfred Stieglitz, who helped Smith show her work. Some of her pieces are now part of the Stieglitz/Georgia O'Keeffe Archive at Yale University.

Many fine artists have been inspired by the Rider-Waite-Smith deck and by tarot, generally. Some decks are made in the style of artists like Mucha and Dürer, but some artists like Salvador Dalí actually designed their own decks. His cards mix classical European art traditions with Pop and Surrealist elements to create an ambitious set of (slightly spooky) cards.

Leonora Carrington – another famous Surrealist – also made a set of paintings inspired by tarot. 'She would show [a tarot] image that would be standard in a certain sense, but there would be these various Carringtonesque qualities to them. Like, the central figure would be a woman that would have been seen in one of her paintings,' says Rachel. 'And vice versa – figures of the tarot can be seen in some of her paintings. If you know that she does tarot you start recognising things in her paintings.'

The Tarot Garden of Niki de Saint Phalle in Capalbio, Italy

Artists haven't only thought about tarot two-dimensionally – French-American artist Niki de Saint Phalle created her famous Tarot Garden in Italy, which is filled with monumental tarot-inspired sculptures. The garden took 15 years to complete and the artist lived in the Empress tower during a portion of the construction process. The garden is open to the public, and visitors can go inside some of the sculptures. Saint Phalle also issued a set of Major Arcana cards once the garden opened.

'What's interesting, I think, for artists is that it's very vivid imagery, but also mysterious,' says Rachel. 'I think that draws artists who want to explore something – who want to explore imagery that's evocative and has connections to spiritual traditions, but is not absolutely hard and fast.'

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes