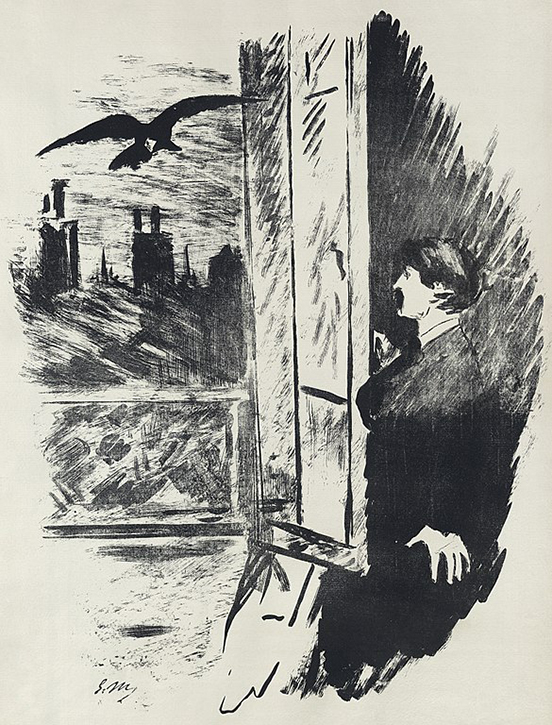

Illustration for a French translation of Edgar Allan Poe's 'The Raven'

1875 by Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

Art Matters is the podcast that brings together pop culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

Download and subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher or TuneIn

Are you into zines? What about comics? From medieval illuminated manuscripts to zines you can pick up at your local art fair, artists have had a special relationship with books for centuries. I came across some examples of books that had been illustrated by artists such as David Hockney and Marc Chagall. This inspired some questions around artists working as illustrators, and ideas about the differences between the two.

‘Artisans of various kinds have been involved in decorating books or illustrating them in some fashion ever since the beginning of codex books, which we can date from around the time of the second century (current era),’ says Jaleen Grove, an artist

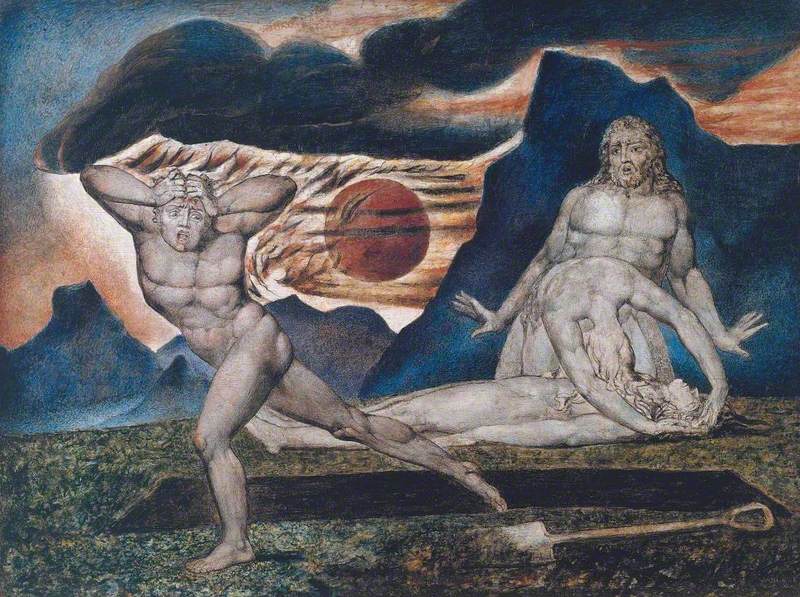

The Inscription over the Gate

1824–1827, graphite, ink & watercolour on paper by William Blake (1757–1827)

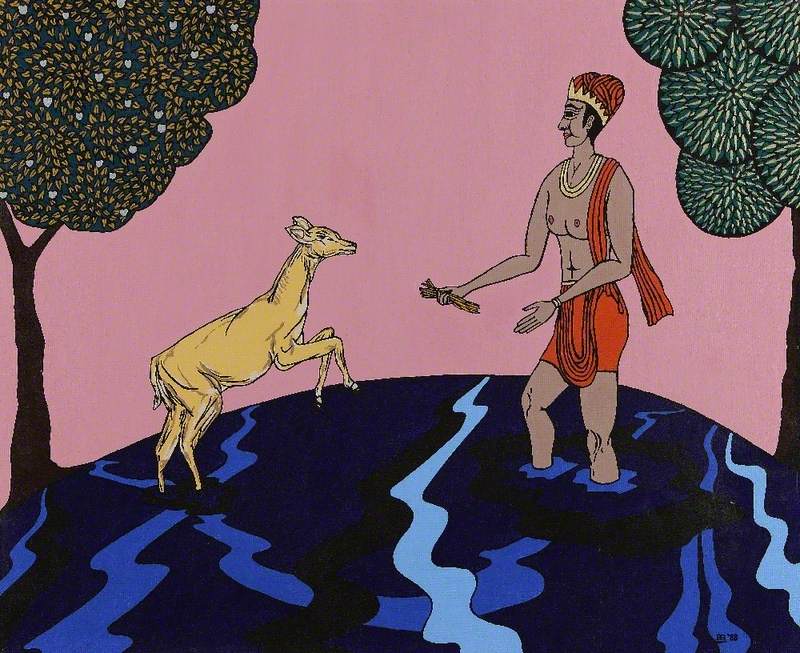

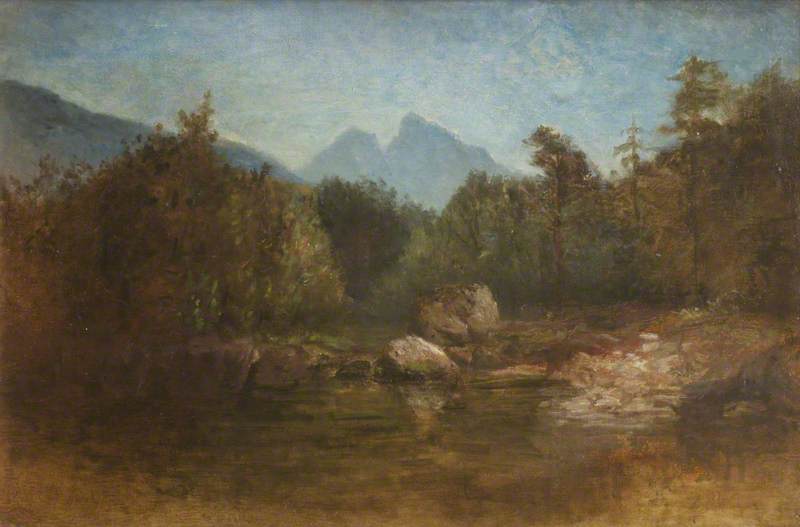

‘[William Blake] was a bit of a mystic, and his books are generally spiritual in nature, but there’s also themes of nationalism,’ says Jaleen. William Blake painted several biblical scenes that one could argue are illustrative in nature, including his famous work, The Body of Abel Found by Adam and Eve, which shows Cain fleeing after murdering his brother. In 1825, however, he was explicitly commissioned to illustrate Dante’s Divine Comedy – a literary classic that takes the reader on a poetic journey through Hell. In a palette of blues and reds, Blake created over 100 illustrations for the poem left in varying stages of completion when he died.

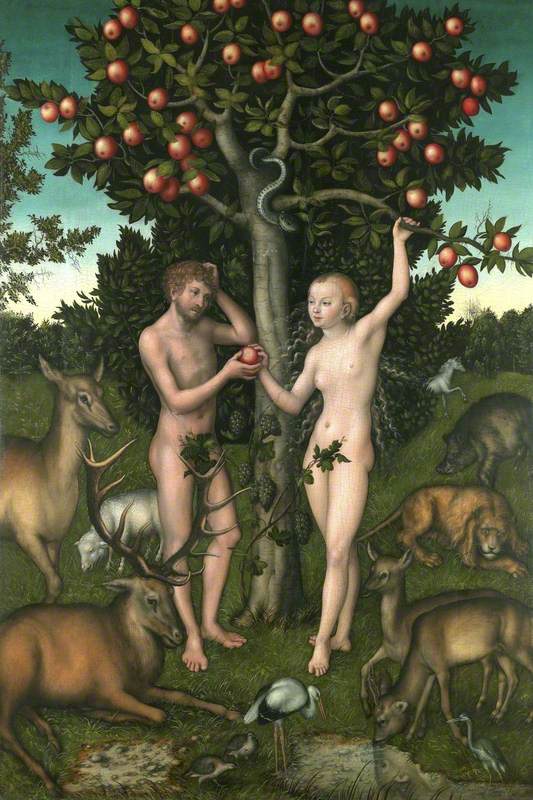

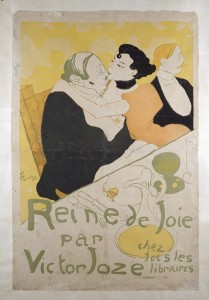

‘We don’t really see self-assigned book projects by artists or illustrators until we get further into the nineteenth century, and this really starts to ramp up towards the 1890s, but we have an early predecessor in the 1870s with Édouard Manet,’ says Jaleen. Manet was a celebrated French Realist and painter of works like Le Déjeuner

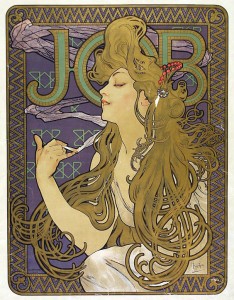

The Flying Raven

(Ex Libris for 'The Raven' by Edgar Allan Poe), 1875, lithograph on simili-parchment by Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

Manet had been working with printmaking techniques for some time when Stéphane Mallarmé decided to translate Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven into French and asked Manet to do the illustrations. He created dark, moody illustrations that reflected the tone of Poe’s famous poem. The style is painterly, with swathes of black ink and dynamic lines dashed across scenes. It also appears that Mallarmé may have been his inspiration for the drawing of the main character, as the distinct

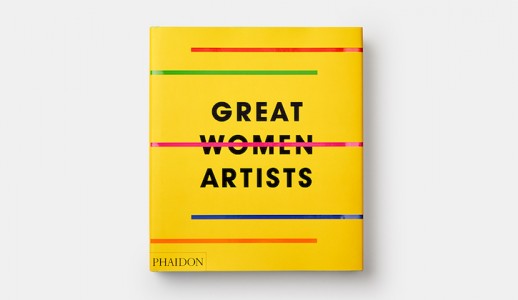

‘Artists’ versus illustrators

There’s frequently a distinction drawn between what makes an ‘artist’ and what is a craftsman or tradesman. In this story, we seem to be talking about artists working as illustrators as if they aren’t one and the same, and I think it’s important to understand the thinking behind this delineation.

‘We’re talking about a European tradition where people who were tradesmen or women were considered to be of a lesser class,’ says Jaleen. ‘People who were aligned with engraving came out of a guild tradition – as did painters for a really long time – and as the print technologies evolved between 1450 and 1900, we see a

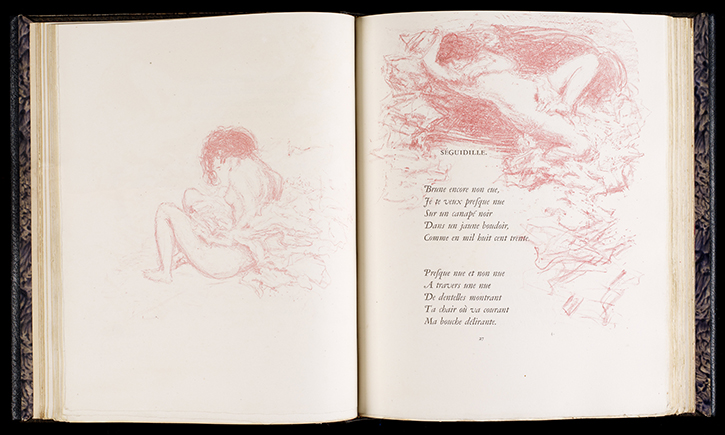

Parallèlement

1900, lithographs in rose ink, wood engravings, and letterpress by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947)

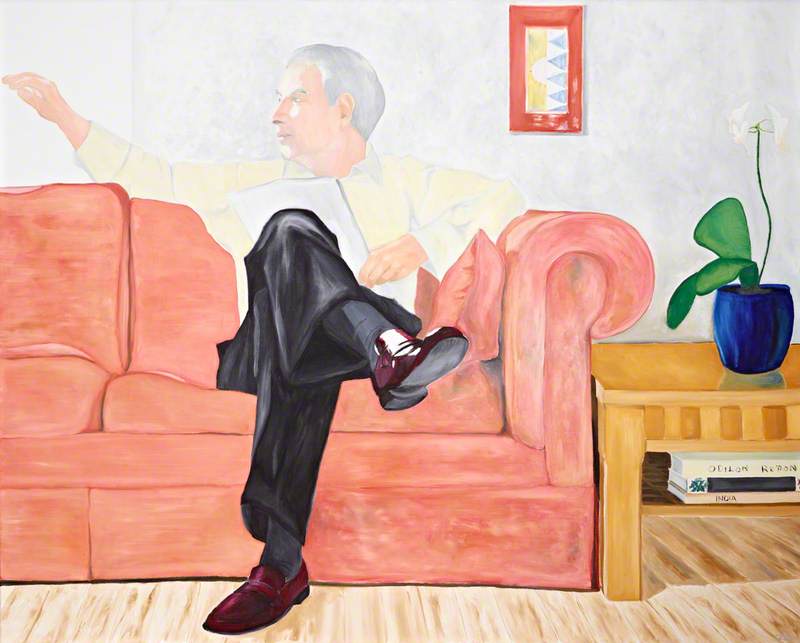

After Manet, artists became more interested in exploring the relationship between books and their fine art practice. As we move into the modern era, we see the birth of the livre

This experimental bookmaking carried on into the twentieth century, with the Futurists, Dadaists, Surrealists and other avant-garde artists dabbling in the medium. Sometimes the books came in small print runs, and sometimes they might be one of one. With the livre

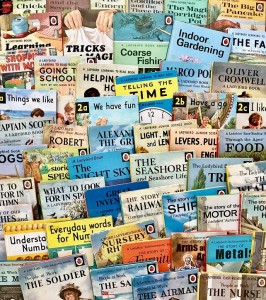

Artist’s books haven’t disappeared – if an artist isn’t creating a book in this traditional sense, they live on in more contemporary versions like comics and zines. ‘This livre

If you’d like to find out more about Jaleen Grove, you can visit her website to learn more about her art practice and research. If you enjoyed this episode, you may also like episode 11, where I speak to Cedar Lewisohn about artists who’ve made cookbooks. Be sure to listen to the full episode in the link above – or wherever you listen to your podcasts – to hear greater detail on this topic and other examples of artist-illustrated books.

Explore more

Art Matters podcast: when artists make cookbooks

Leafing through the pages in the nation's collection

Mythstories: using art to tell tales

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes