Art Matters is the podcast that brings together pop culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

Download and subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher or TuneIn

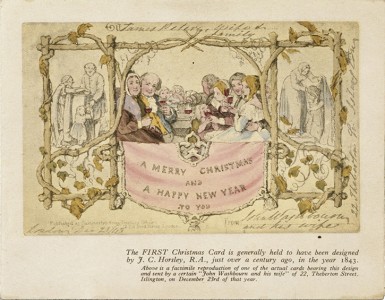

The internet has made sharing new ideas and inventions as easy as clicking a button. People sometimes say this connectivity has made the world feel smaller, and one only needs to think back 20 years to remember how even a simple international phone call was an expensive rarity for most people. Now apply this idea further back to the nineteenth century, and imagine how challenging it would have been to disseminate new technological and cultural achievements across the world. World's fairs provided a platform for nations to showcase their strengths. The first world's fair took place in London, but it was inspired by what the British had seen done nationally in France.

'It was Henry Cole in Britain who said to Prince Albert, why don't we have this as an international event,' says Caroline A. Jones, author of the book The Global Work of Art: World's Fairs, Biennials, and the Aesthetics of Experience. 'The people who organised it in France were already thinking to themselves, we should be inviting the people of the world and the nations of the world to represent themselves in this trade fair as a kind of competition. But the British got ahead on that initiative and produced the Great Exhibition.'

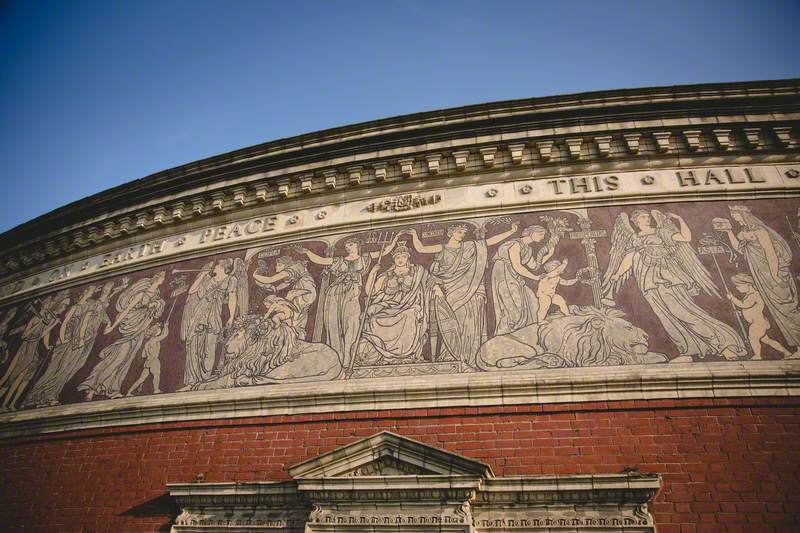

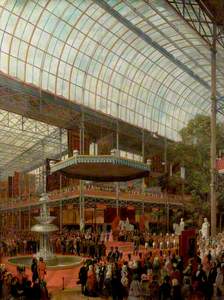

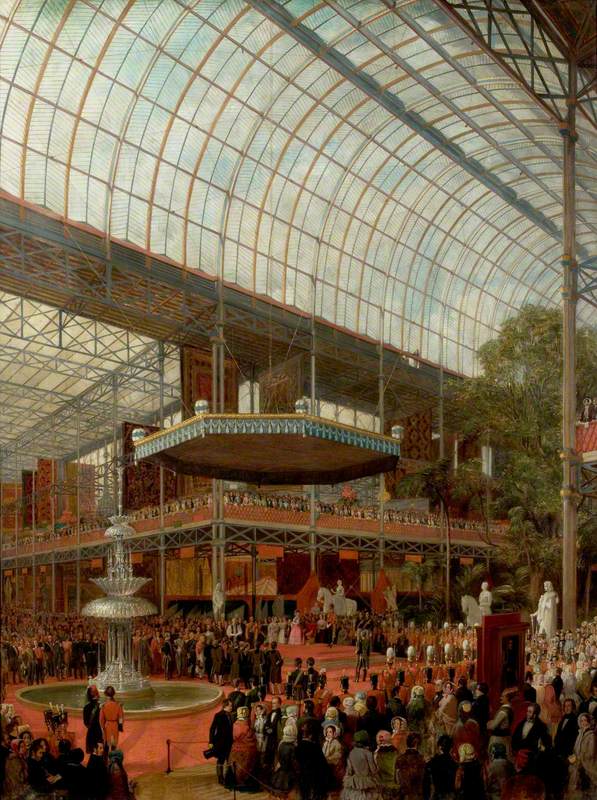

The Great Exhibition was a huge affair, lasting from 1st May to 15th October 1851. It focused on Britain's strengths as an industrial leader, with inventions like the telegraph and voting machine making their debut. One of the grandest achievements of the event was the purpose-built location known as the Crystal Palace.

'[The Crystal Palace] was a modular structure manufactured on-site, piece-by-piece, by people who were trained by [Joseph Paxton], who was the queen's gardener. The maker of the queen's greenhouses figured out how to scale up this technology to make an enormous multistory structure,' says Caroline.

The Opening Ceremony of the Great Exhibition, London

1851

James Digman Wingfield (1800–1872)

In a painting by James Dingman Wingfield, we get a sense of the incredible scale of this structure. The painting shows a large gathering of people in the two-story building. Throughout the scene, you'll find a large fountain, trees, and sculptures. Wingfield also included portraits of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and other recognisable figures in the painting.

The original structure was in Hyde Park and was three times the size of St Paul's Cathedral. A venue this grand certainly sent an international message of Britain's industrial prowess, but there were domestic political motives as well.

'There's some evidence in the archives that Prince Albert really imagined this world's fair as a way of averting worker unrest. In other words, if the workers of Britain could be proud of their productions, presenting them to the world, they could perhaps alleviate the feelings of labour unrest that were roiling across the continent across the English channel,' says Caroline.

Fairs might last around six months, and it was a booming business. People might by a week pass or a book of tickets to attend, and railway packages were designed to encourage travel from around the country. The goal with selling tickets was to recoup the costs of hosting, but the Great Exhibition was so successful that some of the profits were used to later found the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum in London.

Though we're discussing art that could be found in and around the fairs, I wanted to note the diverse range of amazing things that made their debut at a world's fair. That list includes cotton candy, the Ferris Wheel, the telephone, ice cream, x-ray demonstrations, broadcast television and so much more. One really gets the sense that these fairs were such a wonderland to experience. Though the fairs arguably skewed towards industrial innovations, different nations prioritised different aspects of their culture and economy.

'Britain was not very attentive to the production of art because it wasn't part of its national self-image as an art-producing nation. In contrast, the periodic world's fairs that were staged in France were centrally organised around the idea of what the French called the beaux arts, or the fine arts,' says Caroline.

Fishermen carrying a Drowned Man

probably 1861

Jozef Israëls (1824–1911)

Often, the art featured inside the fairs was representative of styles promoted by national academies, which were decidedly not avant-garde at this time. During the 1851 exhibition, Courbet set up an independent pavilion outside of the official fair where he shows his Realist paintings, challenging this academic style, and showcasing works for which he's come to be most famous. Jozef Israëls, who was showing a painting in the official pavilion for the Netherlands, was so moved by Courbet's display that he changed his style. He begins to work in an international Realist style, painting scenes of fishermen and working-class people.

Déjeuner sur l'herbe

c.1863–1868

Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

Courbet set a tone that would be followed by subsequent artists, not only in terms of his painting style, but also in his DIY approach to exhibiting during the world's fairs. French Realist Édouard Manet took a similar approach a decade later, opening a pavilion next to Courbet during the 1867 fair.

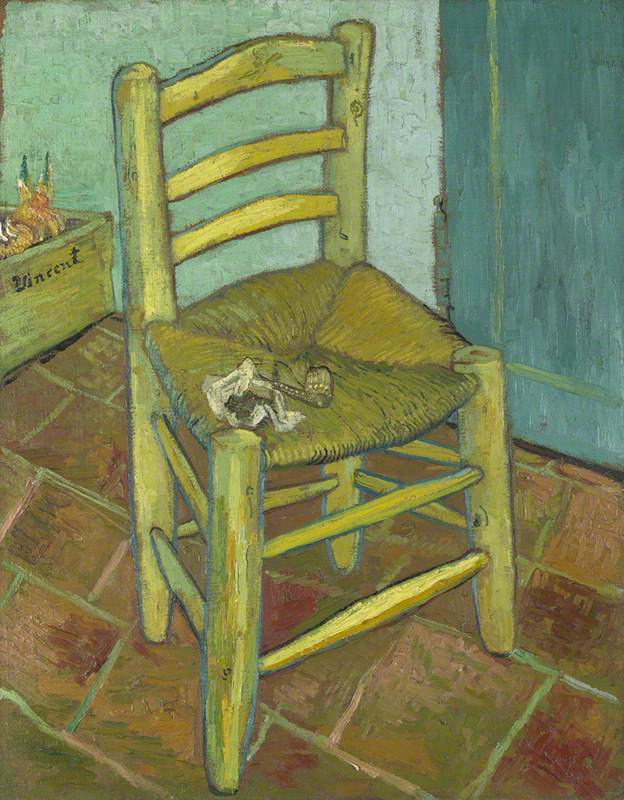

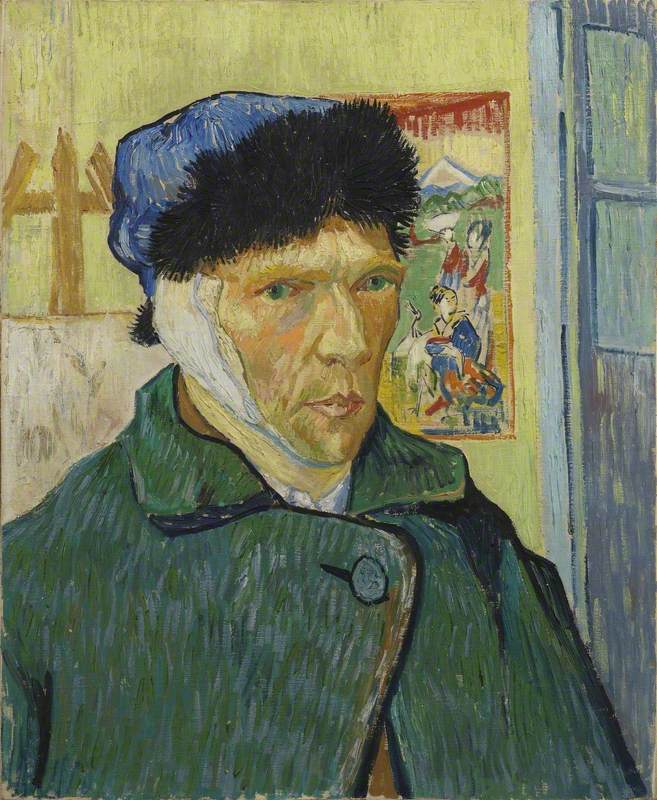

Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear

1889

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)

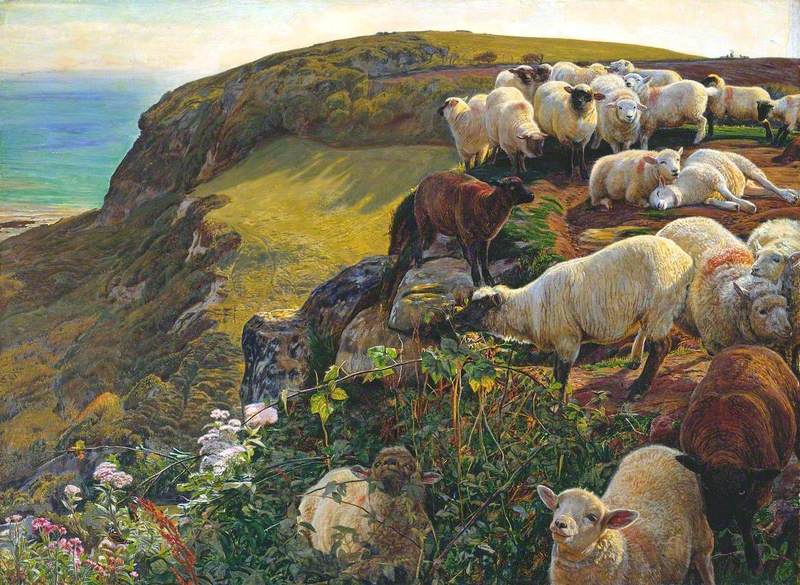

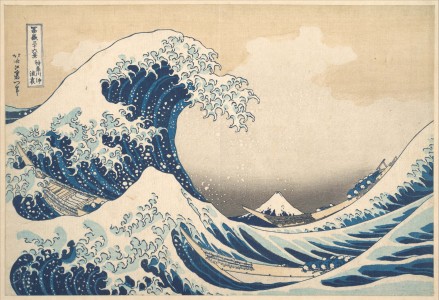

Inside the fairs, there were still important moments occurring in art history. Eugène Delacroix, William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais were amongst the artists who showed work at the 1855 exhibition in Paris. In the 1867 fair, Japan showed art for the first time, and artists including Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Matisse and many other Post-Impressionists were subsequently inspired by the designs of the ukiyo-e woodblock prints introduced to France.

Auguste Rodin also has an interesting relationship with world's fairs. A bronze version of his sculpture The Kiss was on display at the 1893 fair in Chicago, but the subject was deemed so risqué that visitors could only see it by request. That all changed at the 1900 fair in Paris, where he showed again and was subsequently inundated with commissions for portrait busts.

Even if the world's fairs tended to be a bit more conservative, it's interesting to see how the styles of art exhibited at these events changed over the centuries. As art in fairs has evolved into biennials showcasing art from around the world, we begin to see an interesting cultural dialogue.

'We no longer have a manifestly centred curatorial structure that begins from the French academy and fans outward to what are constructed as the peripheries of Europe. We begin to change the story.'

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes