If you cast your eyes around the walls and ceilings in National Trust houses, you will no doubt be pleased with ‘the fine effect’ they have on you.

On 8 September 1780, Antonio Zucchi, the eminent Venetian painter of decorative schemes, who worked most notably for the architect Robert Adam, wrote to his long-term client, Sir Rowland Winn (1739–1785), 5th Bt of Nostell Priory, about his forthcoming marriage to the celebrated artist Angelica Kauffmann. The letter, written in familiar terms, shows the development of a fairly intimate relationship between artist and client established over more than a decade of Zucchi’s professional career in England.

Chloe Playing the Lyre to Daphnis

(or ? Sappho and Anacreon) c.1776

Antonio Zucchi (1726–1796)

Zucchi enjoyed a great deal more autonomy than Robert Adam’s other contractors. He had already been employed by Adam in 1757 and had travelled around Italy with his brother James Adam in 1759. In 1766, Zucchi was persuaded to come to England accompanied by his brother Giuseppe, an engraver. There he established himself as a painter using a Rococo pastel palette from his native town of Venice, which became well suited to the interior design of the Adam brothers.

Zucchi painted roundels, overdoors and inset ceiling paintings for the Neoclassical town and country houses being built at the time, notably the National Trust properties of Saltram, Devon (1768), Nostell Priory, Yorkshire (1767–1776) and Kedleston, Derbyshire (1769–1777) as well as the London houses of Osterley Park (1767), Kenwood in Hampstead (1772) and Home House, 20 Portman Square (1773).

At Nostell Priory, Zucchi made pictures for the Saloon, Library and Lady Winn’s Dressing Room – now the Small Dining Room.

Catullus Comforting Lesbia over the Death of Her Pet Sparrow and Writing an Ode

c.1773

Antonio Zucchi (1726–1796)

In a previous letter to his patron in December 1772, he had written that he would choose such subjects that may be agreeable to her Ladyship’s taste and that would fit in with the others in the room. Because one scene is of Angelica and Medoro: Medoro Carving the Name of Angelica into the Trunk of a Tree, the subject matter of the whole group was contrived as being episodes from Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso (1516), the sequel to Matteo Maria Boiardo’s Orlando Innamorato (1495).

Angelica and Medoro: Medoro Carving the Name of Angelica into the Trunk of a Tree

c.1773

Antonio Zucchi (1726–1796)

For many years all six scenes had been attributed, erroneously, to Zucchi’s wife, Angelica Kauffmann. In other depictions of the scene, Angelica is very often seen carving on the tree, but in the Nostell picture, the name ‘ANGELICA’ has already been carved and the beginnings of ‘MEDORO’ can be seen in the letters ‘ME’ with half of the ‘D’. This inclusion has been read as a signature, suggesting that it was a conceit for Rowland Winn from the female artist Kauffmann.

This story was perpetuated by Maurice Brockwell in his 1915 collection catalogue for Nostell Priory and there has been no reconsideration of the subject matter until now, even though the attribution of the pictures has been corrected since Brockwell’s catalogue.

A closer examination of the five other scenes shows obviously different iconography, which, thanks to Art UK photography, confirms they are: Hector and Andromache (from Homer’s The Iliad)...

Rinaldo and Armida (from Tasso’s, Jerusalem Delivered, II Canto 17–20)...

The Return of Telemachus (from Homer’s Odyssey, Book 17)...

and Cupid Preparing Venus for an Amorous Encounter with Mars.

Cupid Preparing Venus for an Amorous Encounter with Mars

c.1773

Antonio Zucchi (1726–1796)

In the last, an attendant is holding a cuirass and Cupid is at the feet of Venus, who sits on a bed and is playing with a satin ribbon on her shoe whilst she points at the attendant; Mars cannot be seen but has left his shoes on the floor in the foreground. It is tempting to think that this is a depiction of Helen and Paris with Venus' intervention from Ovid’s Heroides, which was becoming a popular subject at the time, but it is not conclusive.

The final scene is less obvious but is probably Dido and Aeneas.

It most likely alludes to Virgil’s Aeneid, Book IV when the pair go out hunting together and when it rains Dido lures Aeneas into a cave to consummate her love for him, rather than, as has also been suggested, from Book I, when Aeneas’s mother Venus, disguised as a huntress, guides him to Dido after his shipwreck. Aeneas is also usually accompanied by Achartes as seen in Kauffmann’s picture at Saltram.

Venus Directing Aeneas and Achates to Carthage

1768

Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807)

It is also tempting to suggest that this final scene is Inibaca and Trenmor (The Power of Love) from the forged Celtic poem compilation, Ossian’s Fingal by James Macpherson (1736–1796) which Angelica Kauffmann herself had exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1773 (Private Collection; owned by a Home descendant) showing the moment when Inibaca, dressed as a soldier, reveals herself to Trenmor. However, the image does not quite fit the text, as she is not dressed up as a man and he has no spear, which is a shame as the poem compilation was a very topical reference at that time and Zucchi painted it elsewhere.

Similar subjects to the Nostell overdoors were treated by Angelica Kauffmann in her history paintings and indeed the more senior artist Zucchi's work has often been confused with hers. They probably met in London soon after Angelica arrived in 1766 and, along with Sir Joshua Reynolds, co-founded the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768, of which Zucchi became an Associate in 1770.

Although it is often suggested that the couple collaborated in houses, there is no real documentary evidence for this, as they painted in their respective studios in London rather than in situ.

It is not known when they began courting, as Angelica had been fraudulently married and had to wait for a Papal annulment before re-marrying, which she finally received in 1780. Also, Angelica was mainly making her name in her portraiture of the aristocracy and free hanging ‘history’ paintings that she exhibited at the Royal Academy. However, Zucchi and Kauffmann probably shared knowledge and suggestions for types of scenes from classical literature and also contemporary writing on British history.

Kauffmann’s renderings of many of the same subjects are chronologically later and sometimes more sophisticated re-workings of Zucchi’s ideas. Although it is mentioned in the Zucchi/Winn correspondence that Zucchi sent prints of Kauffmann’s work to Winn as presents, none of these are in the collection at the house in Yorkshire now and the only painting by her: Self Portrait of the Artist Hesitating between the Arts of Music and Painting, was not acquired until the twentieth century.

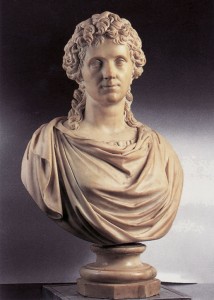

Self Portrait of the Artist Hesitating between the Arts of Music and Painting

1794

Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807)

All the Nostell pictures have the theme of loss, longing and return, including feminine love defeating masculine aggression, which would perhaps have more feminine appeal, and is why they were for a long time attributed to the female artist rather than just, as it has transpired to be, the pleasing of a female patron by a sensitive male painter.

I am grateful to Frances Sands, Adam Drawings Project at Soane Museum for publishing transcriptions of the correspondence from the West Yorkshire Archive Service, in 2011.

Tania Adams, Former Paintings Project Cataloguer, National Trust