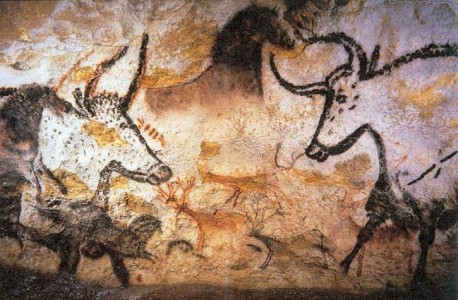

The saints and heroes that populate the Renaissance imagination are accompanied by a host of charismatic animals. The animal kingdom has long been a rich source of symbolism – in the medieval period, bestiary manuscripts assigned a moral meaning to the behaviour of different creatures. In the Renaissance, animals frequently appeared in paintings as metaphors or emblems.

Portrait of a young Man holding a Dog and a Cat

Dosso Dossi (c.1486–1542) (attributed to)

In portraits, they were sometimes used to demonstrate the character of the sitter. Dosso Dossi's A Young Man Holding a Dog and a Cat in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, is a particularly beguiling example. The shadowy faces of the cat and dog are perhaps manifestations of opposing sides of the man's personality. These are ordinary creatures that we know well today, but they give the painting an alluring atmosphere of melancholy and mystery.

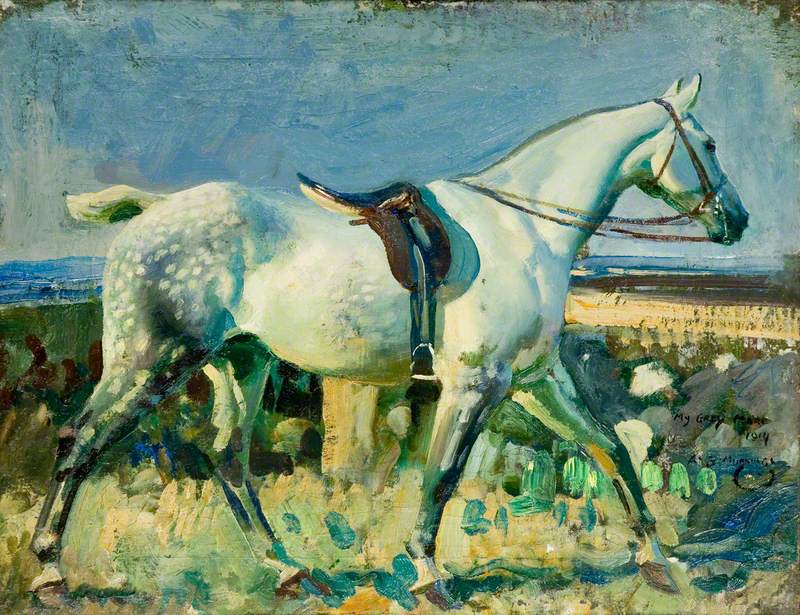

There are some other intriguing Renaissance paintings with animal protagonists in the Ashmolean. Perhaps the most famous is Paolo Uccello's The Hunt in the Forest, a panoramic scene of a night-time chase. Hunting during the Renaissance was associated with marriage, with the pursuit of the animal representing the pursuit of the beloved. Its aristocratic associations also made it a sign of prestige and virtue.

The painting is alive with raw animal energy: sleek, long-legged hounds zig-zag through the trees and statuesque horses gallop behind. The perspective, as always with Uccello, is mathematically calculated, but the dynamism of the scene interrupts this careful precision. The composition oscillates between order and chaos – neatly receding space and the turbulence of motion. We can sense the stomp of the horses' hooves and the whoosh of the dogs as they fling their bodies through the air.

Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Artists, gives a vivid account of Uccello's love for the animal kingdom: 'he kept ever in his house pictures of birds, cats, dogs and every sort of strange animal whereof he could get the likeness.' The name 'Paolo Uccello' actually means 'Paolo of the Birds' and was given to him because he was so fond of animals.

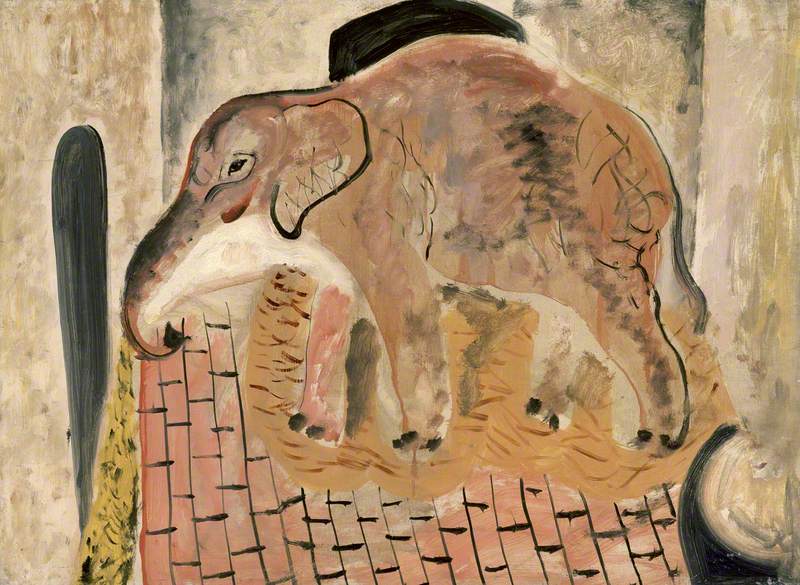

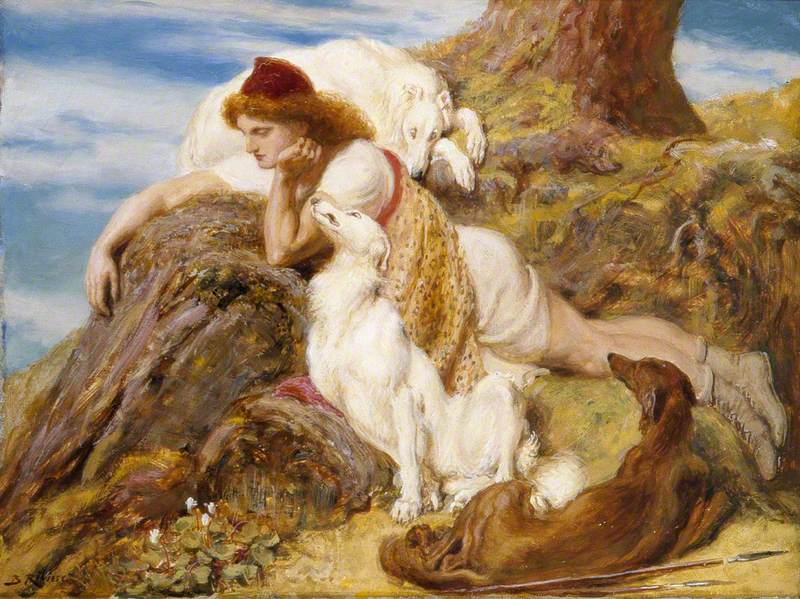

Like Uccello, Piero di Cosimo is characterised by Vasari as an eccentric. He had 'the life of a man who was less man than beast', avoiding the company of others, letting his garden grow wild 'like his own nature.' He died having 'reduced himself to a state with his extravagant fancies.'

His spectacular painting The Forest Fire is as eccentric, extravagant and wild as he is supposed to have been himself. It takes its inspiration from the Roman philosopher Lucretius, whose poem De Rerem Natura details how the power of fire led to the development of human civilisation. The poem was widely read in Piero's time and evoked a distant, primitive past when humanity was still not quite separate from nature. This semi-mythological setting accounts for the strangest detail of all in the picture: the little human faces on the bodies of some animals. Infrared reflectography has revealed that these were last-minute additions, moments of witty improvisation.

Even without human faces, the animals in this painting are bursting with charisma. Their reactions to the flames are strikingly convincing: the birds swoop out of danger to settle in the trees, the cow's tongue lolls from its mouth, and the bear pants as it staggers away from the flames. There's a strong sense of the warm, earthy bulk of their bodies and the smoky heat of the atmosphere.

The lions in The Forest Fire are at home in the wild landscape, but the magnificent lion in Titian's The Triumph of Love seems a little out of place against the backdrop of a Venetian lagoon – and with a small boy balancing rather precariously on his back.

The boy is, of course, Cupid. The image of a cupid riding a lion was a common theme in classical and Renaissance art, representing the Virgilian maxim Amor vincit omnia – love conquers all. Lions were viewed as symbols of pride and wrath, the emotions to be tamed by love.

The painting was made for wealthy art collector Gabriel Vendramin as a cover for another of his paintings. These painted covers, called timpani, were used to tantalisingly suggest the image beneath, and to create a moment of revelation as it was uncovered. The painting that The Triumph of Love covered was perhaps a portrait of Vendramin's lover, or more likely that of an ideally beautiful muse. Together, portrait and timpano were a poetic evocation of perfect love and beauty, suitable for intimate and contemplative viewing in the setting of Vendramin's camerino.

Another example of animals in Renaissance Venetian paintings can be seen in this devotional portrait of the Vendramin family, which features a puppy held by one of the boys.

Although the dog was most likely painted from life, Titian probably modelled his lion on sculpted examples, such as the famous bronze lion of San Marco, which sports a similarly gaping mouth and fabulous mane. Vendramin also had a small bronze sculpture of a cupid standing on a lion in his collection. Titian's lion writhes angrily under the little cupid, its eyes gleaming and its fur soft and heavy. Compelling and imposing, it attests to the symbolic power of love and adds a vibrant exoticism to the image.

Here's another small boy riding improbably on an animal: Francesco Bianchi Ferrari's Arion riding on a Dolphin.

Arion riding on a Dolphin

c. 1509–1510

Francesco Bianchi Ferrari (c.1460–1510)

As with The Forest Fire, the setting is a long-distant semi-mythological world. The subject is taken from the ancient Roman poem Fasti by Ovid, a celebration of the myths and customs of the Roman calendar. Ovid tells the story of Arion to mark the arrival of the Dolphin constellation in the sky, in early February. During a storm, sailors threw the singer Arion into the sea because they were after his winnings from a music contest. He charms a dolphin with his music, who brings him safely back to shore.

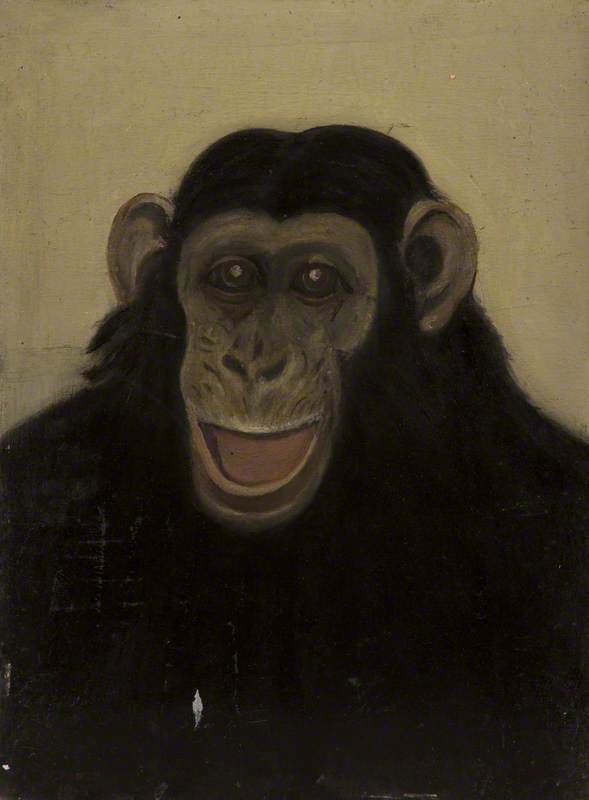

This is the Renaissance imagining of a dolphin – a serpentine body with a bulbous head and human-like eyes that stare piercingly out at us. It is a strange little painting, and as with the other paintings, it is the animal presence that gives it its special, magical atmosphere.

The animals in these images bring the scenes to life with their personalities and energy. In a night-time forest, a burning ancient landscape, a Venetian lagoon or a windswept sea, these painted animals have puzzled, engaged and delighted viewers down the centuries.

Catherine Jamieson, undergraduate at the University of Oxford and winner of Write on Art 2018