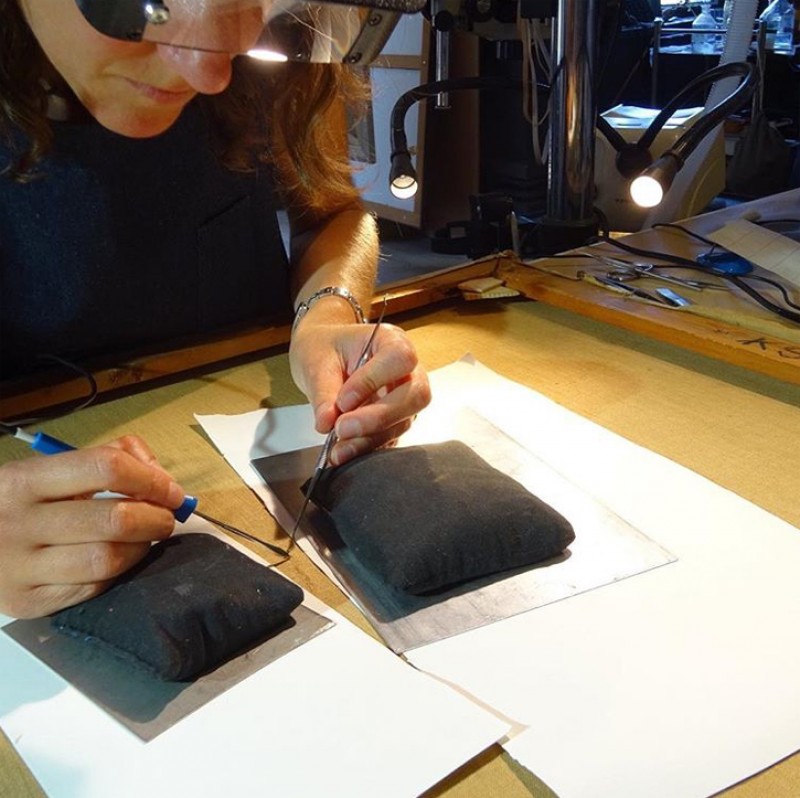

In this series, 'Conservation in focus', Simon Gillespie, Director of Simon Gillespie Studio, explores the art of conservation. In each article, Simon looks in depth at a particular technique or tool that is crucial to conservators and explores the challenges – and triumphs – associated with their everyday work.

The first tool a conservator uses when assessing a picture is their eyes. It sounds obvious, but it is not to be underestimated!

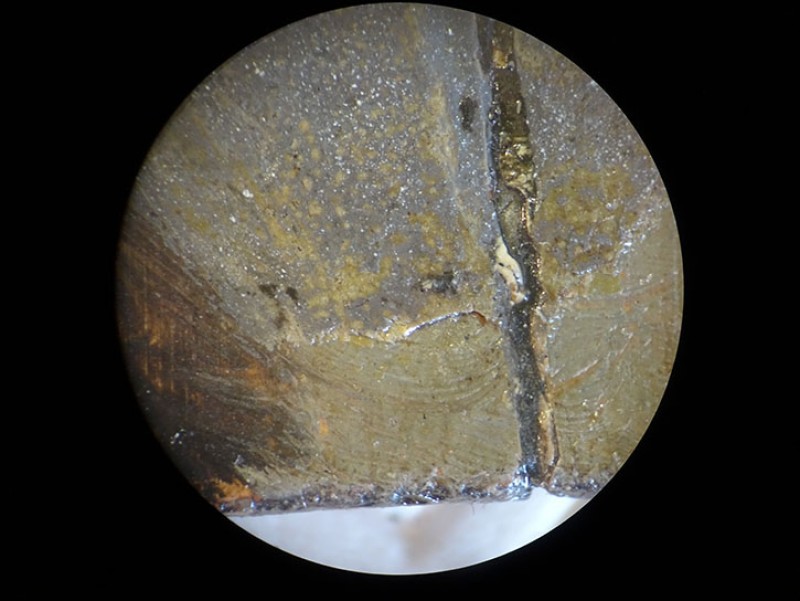

As a conservator, I have spent thousands of hours treating artworks – looking at them very closely, under the microscope, in different lights; handling them; discussing them with colleagues; assessing how they each respond to a certain treatment versus another. I have attended lectures, workshops and conferences where other conservators talk about what they have seen when treating artworks, how to recognise certain issues, and how to treat them. I have seen the results of good conservation and bad.

Someone who often does mental arithmetic will be able to tell you the answer to 'seven times eight' in a heartbeat: the pathways in their brain are primed for such questions and they don't even need to think about the answer. In a similar way, when I carry out an initial 'visual assessment' of an artwork, some things will immediately be apparent to me due to my experience: perhaps something about the materials, its likely age, where it's been stored or displayed, whether it's been damaged in the past, whether it's been cleaned or treated before, if it has underlying issues. And having spent hours looking closely at paintings, I have a visual bank of knowledge in my head that sometimes enables me to recognise a painting as being by a particular artist and not another, from looking at the style, brushwork, colours and technique. Bendor Grosvenor has a lovely metaphor for this process: he compares it to recognising the handwriting of a close friend or relative.

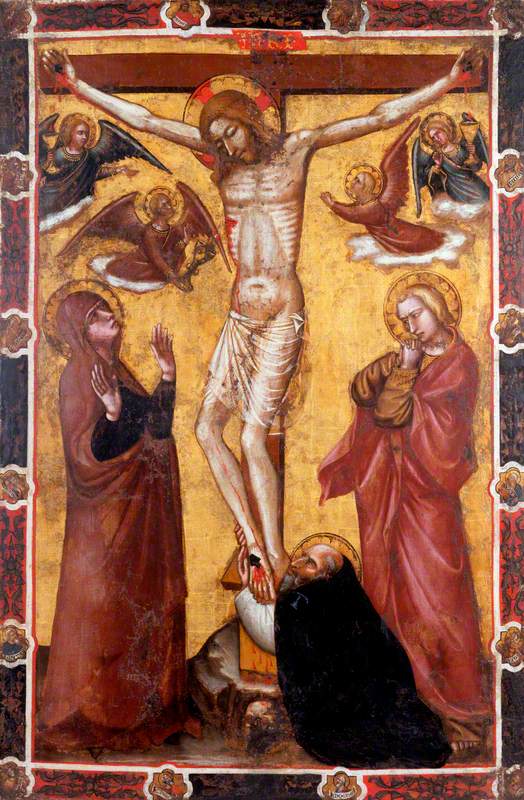

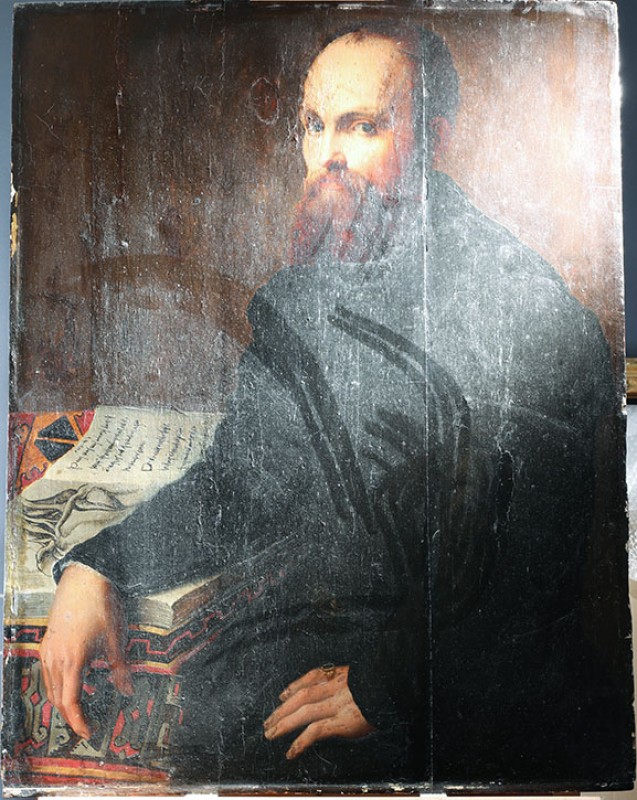

Detail of 'Portrait of a Man'

16th C, oil on canvas by Antonis Mor (1512–1516–c.1576). Hospitalfield

For example, when I first looked at the portrait of a man from Hospitalfield House which was eventually successfully attributed to Antonius Mor in season two of Britain's Lost Masterpieces, I saw that it had Mor's characteristic two highlights in the eye (one in the orb of the eye and one on the eyelid).

Similarly, when Bendor and I first saw Derby Museum's painting of Nomentano Bridge (it was then known as Landscape with a Ruinous Castle, if I remember correctly, before Bendor identified the actual bridge depicted), we both spotted that the river in the right-hand corner of the painting is painted with a sgraffito technique, where the brush is turned the wrong way around to score into the wet paint using the hard end of the handle so as to convey the effect of ripples in the water. Not many artists used this technique, and one of the few who did was Joseph Wright of Derby, which was our first clue that the painting might be by him. The rest of the river did not look characteristic of Wright of Derby, because it had had overpaint applied to about 80% of the surface: someone had decided they could improve the painting or hide some condition issues by applying paint on top, but instead that someone had made the river seem to flow uphill.

This brings me to another clue visual examination will reveal: I may be able to tell which areas of paint are original to the picture and which are not, and why the later paint has been added.

For example, when the portrait of Richard Vaughan first arrived at my studio from Carmarthenshire County Museum, I could see that the eyes showed true quality: in simple terms, they had been painted by someone who knew how to paint eyes. And I could see that the artist's original soft glazes around the jawline were in good condition: these are the delicate fine layers of transparent paint which will be the finishing touches applied by an artist before a varnish is put on the picture; they are often sensitive to harsh cleaning methods and so are the first thing to be damaged. It is always pleasing to see these intact. But it was also obvious that the area of the forehead had been impaired and that a repair attempt had been made, with paint added on top. I learnt that the painting, before its purchase by the Carmarthenshire County Museum, had been hanging at the dilapidated Golden Grove mansion, in a staircase that had lost its roof, where the picture was therefore exposed to the elements and had rainwater running down it. It's no wonder that some areas of the painting were damaged!

Richard Vaughan (1600–1686), 2nd Earl of Carbery

c.1670

Peter Lely (1618–1680)

A visual examination may also show areas where, in the process of painting the picture, the artist changed their mind about some aspect of the composition. For example: an artist might paint their sitter with a hand on their hip but then decide they would prefer the hand to be resting on a nearby table, so they will paint over their first attempt. Oil paint naturally becomes more transparent as it ages, and so a change of composition that was not obvious when the artist produced the painting might become apparent over time as the top paint layer becomes transparent and allows the first composition to show through.

In other cases, the application of a second layer of paint over the original composition will result in a slightly raised area and the brushwork of the original composition will be discernible texturally underneath the final composition, even if the colours can't be seen. Evidence of a change in composition is called a 'pentimento' and is often seen as a clue that the artwork is original: pentimenti shows the workings of the artist's mind as they make decisions on how to position elements in the composition. A copyist will simply be replicating the original version and so will not need to make those kinds of decisions.

A Country Gentleman

(once said to be Charles Burney) c.1770

Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

To illustrate, during the process of painting the portrait of a gentleman sitting on a tree trunk from Manchester Art Gallery, we can see that Zoffany moved the sitter's right leg and had decided that the sitter's left foot looked too short and its tip should be lengthened to achieve a sense of perspective and depth to the painting.

A visual examination will bring up interesting points of comparison between a painting and other known versions of it. For example, when Bendor first went to see the portrait of George Villiers at Pollok House near Glasgow, which eventually in 2017 was recognised as a lost masterpiece by Peter Paul Rubens, thanks to our work, he could already spot the typical 'Rubensian' way of depicting eyelashes: Rubens often did not paint eyelashes with little lines of dark paint. Instead, he scored into the paint with the wrong end of the paintbrush.

George Villiers (1592–1628), 1st Duke of Buckingham

17th C

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

In another version of this portrait which is in the Pitti Palace in Florence, and which was until 2017 the contender for being the original lost masterpiece by Rubens, the eyelashes were painted in the ordinary way. Another interesting point of comparison is that in the Pollok House painting: we could see pentimenti where the artist had changed their mind about the position of the lace collar, but there were no such pentimenti on the Pitti portrait. These characteristics pointed to the Pollok picture being original and the Pitti one being the work of a copyist.

At a later stage in the conservation process, the Pitti version became unexpectedly useful to us: at some point in history, someone had painted over the background of the Pollok House portrait, and therefore being able to see the colour of the background in the Pitti Palace version (produced before the overpaint had been applied to the Pollok House portrait) gave us an indication of the colour underneath the overpaint.

Simon Gillespie, Director at Simon Gillespie Studio

Previous: What is art conservation?