I vividly remember the moment in childhood when a ladybird crawled onto my palm and then spread its wings wide and vanished. I became enchanted by the natural world and all creatures great and small.

It is with a heavy heart I read the report this year that revealed the fact that rapidly declining insect numbers are causing the 'catastrophic collapse of nature's ecosystems' – more than 40 per cent of insect species are declining and a third are endangered. Then earlier this month the release of the results of a major UN global assessment report revealed that 1 million species are at risk of extinction and due to such declining biodiversity, upon which we depend for our existence, human society itself is under threat.

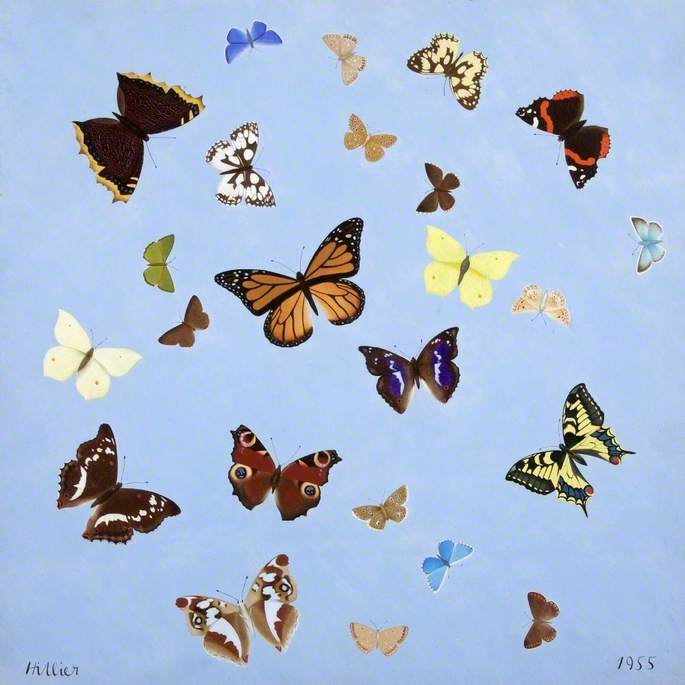

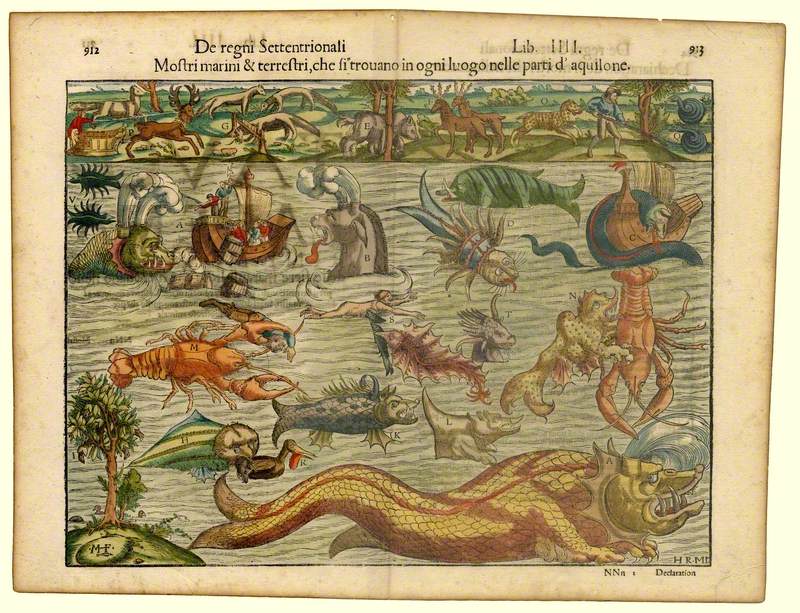

Looking through the astonishing array of artwork depicting insects on Art UK shows how human beings have spent time appreciating these tiny creatures, and it is a reminder to celebrate and respect them. Ladybirds, moths and bees flutter through the archive: woodlice, beetles and spiders galore scuttle through paintings. Inspecting these paintings of insects (and other creepy-crawlies) is a timely reminder of how valuable they are. Insects make up the majority of creatures that live on land, and provide crucial benefits to many other species, including humans. They provide food for birds, bats and small mammals, and they pollinate around 75 per cent of the crops in the world by replenishing soils.

I was reminded of my early fascination with ladybirds by looking at Ladybird by Gary Thrussell (b.1958) held at Chelmsford Museum Store. Stripped of colour it powerfully hints at the loss and vanishing happening in our natural world.

Human beings' hunger to know more about the insect world is well captured as paintings show not only the outside but inside of creatures, as in Insect Dissection by Martin Wells (1928–2009) which is housed in the Department of Zoology at the University of Cambridge.

This painting acts as both magnifying glass and x-ray, showing how intricate and complex the tiniest of creatures are, and the myriad of processes that go into keeping them alive.

By contrast, there are also paintings that maintain the mystery of the natural world, those things we might never know, such as The Secret Language of Insects by Dominic Shepherd (b.1966).

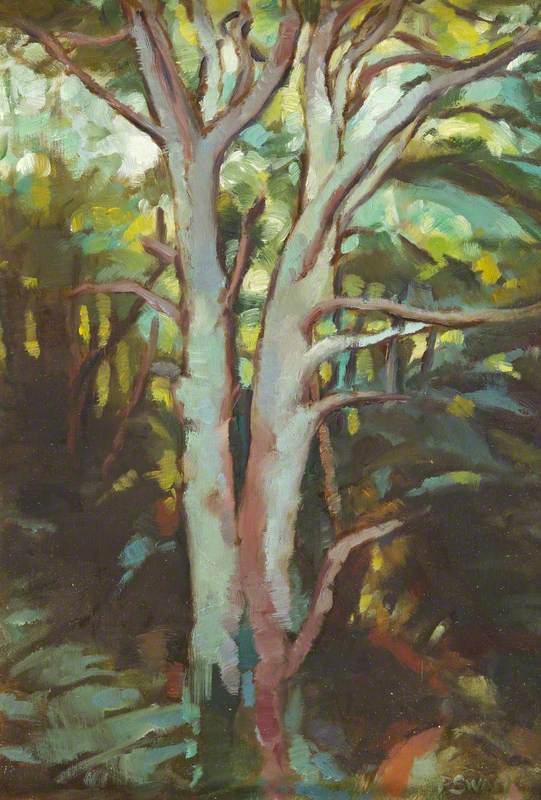

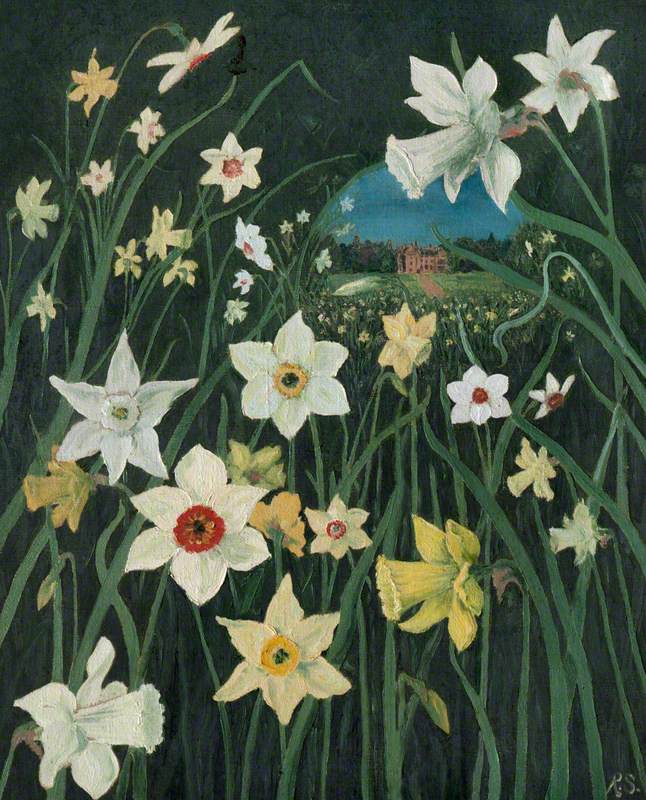

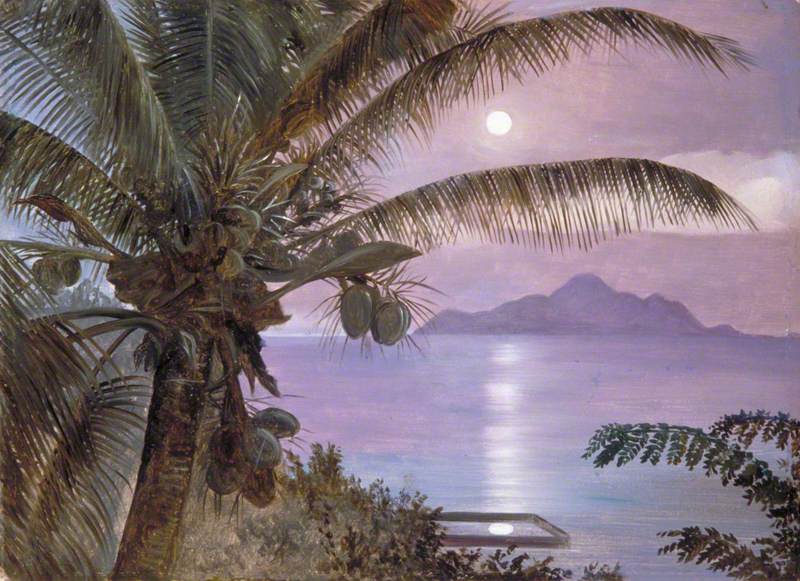

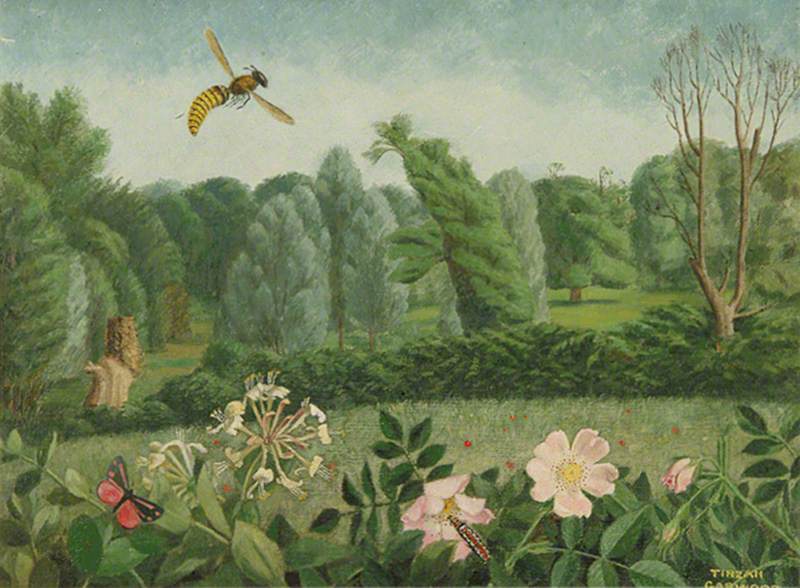

Paintings powerfully show insects in the context of the landscape they inhabit and worthy of note in this respect is the wonderful work of the Victorian botanical artist and biologist Marianne North – to name but a few of her artworks, there is Leaf-Insects and Stick-Insects housed at her gallery in at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Kew, the Marianne North Gallery.

Meanwhile, Leaf Insect brilliantly shows the blending of insect and leaf such that they have become one and the same.

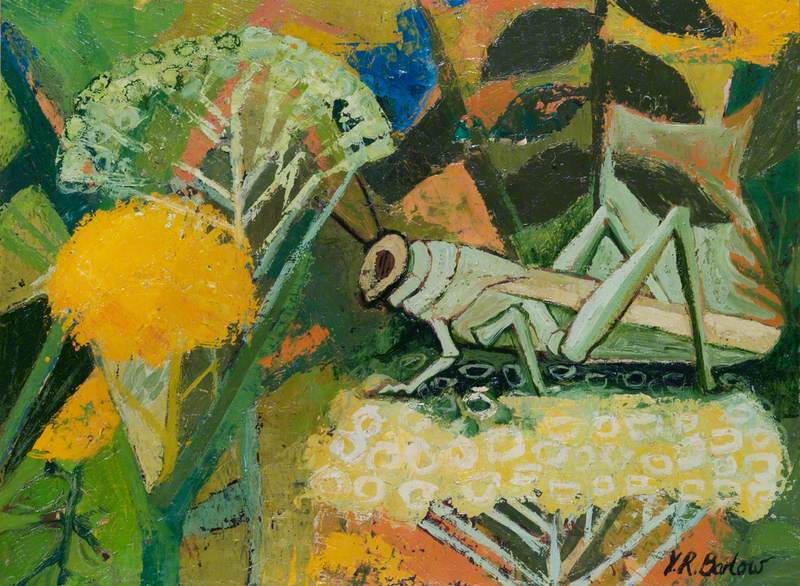

In showing insects in their landscape I also found striking the painting Green Grasshopper by Yvonne Rosalind Barlow (1924–2017) which uses various shades of green to great effect.

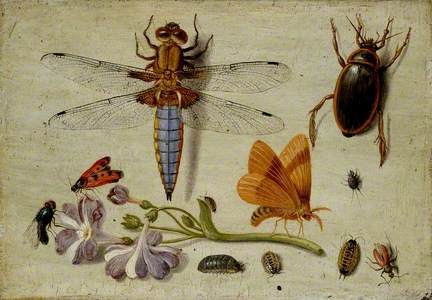

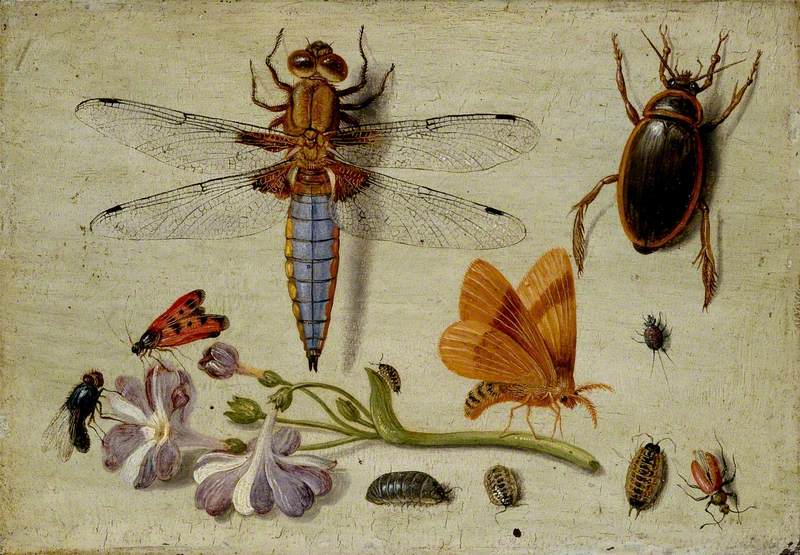

A Dragon-fly, two Moths, a Spider and some Beetles, with wild Strawberries

early 1650s

Jan van Kessel the elder (1626–1679)

Wonderfully drawn out in artworks is the web of connection in the natural world. The food cycle is fascinating to observe, for example. In A Dragon-fly, two Moths, a Spider and some Beetles, with wild Strawberries, a magnificent dragonfly feasts upon a strawberry.

Insects feeding on fruit are also depicted in Fruit and Insects after Abraham Mignon (1640–1649).

Meanwhile, in an untitled artwork by Mandu Mmatambwe Adeusi at the Argyll and Bute Council collection we see a bird about to eat a fly, all while a snake has one of the bird's eggs in its mouth.

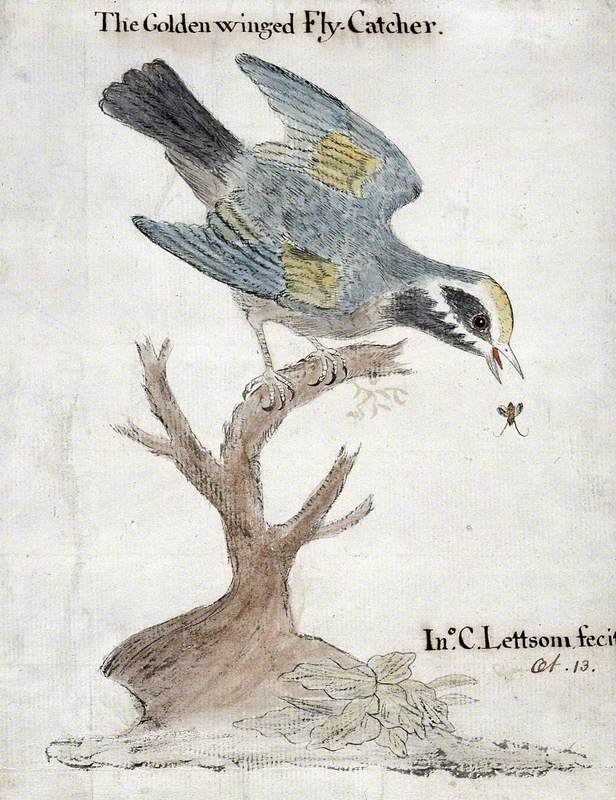

A Golden-Winged Flycatcher Catching an Insect

1757

John Coakley Lettsom (1744–1815)

While insects are the empowered centrepiece in some paintings, in others they are reduced to tininess, and are the ones being consumed, for example in The Golden-Winged Flycatcher Catching an Insect by John Coakley Lettsom (1744–1815), housed at the Wellcome Collection.

Floral Study with Insects in the Foreground

Andries Danielsz. (c.1580–c.1640) (attributed to)

Still Life of Two Jugs with Flowers and Insects

18th C

Jan van Huysum (1682–1749) (style of)

Still Life with Fruits, Flowers and Insects

Philip van Kouwenberg (1671–1729)

Some paintings show the ferocity and wildness of the natural world while others are tamer, and in domesticated scenes show insects indoors as in Floral Study with Insects in the Foreground attributed to Andries Danielsz. (c.1580–c.1640) and Still Life of Two Jugs with Flowers and Insects in the style of Jan van Huysum from the eighteenth century, as well as Still Life with Fruits, Flowers and Insects by Philip van Kouwenberg (1621–1729).

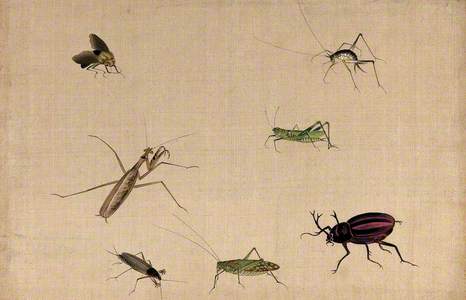

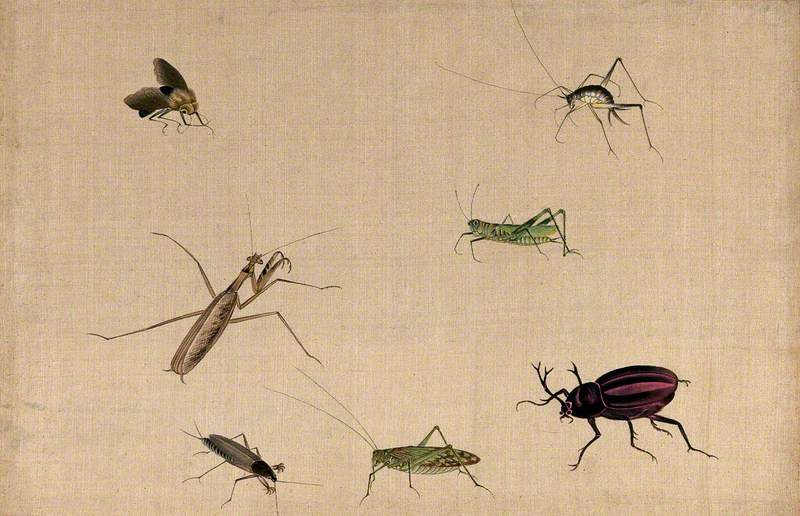

Seven Insects, including a Grasshopper, Praying Mantid and Stag Beetle

unknown artist

Worthy of note too is a series of artworks by an unknown artist held at the Wellcome Collection which strikingly show a varied amount of insects, such as Seven Insects, including Grasshopper, Praying Mantid and Stag Beetle.

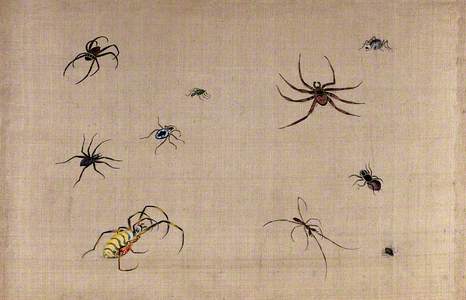

Although technically not insects, but arachnids, let's take a quick look at spiders. Often thought of as undesirable, their beauty is brought out in a work such as Ten Spiders, Showing Much Variation in Shape and Colour.

Various Spiders and Caterpillars, with a Sprig of Gooseberry

early 1650s

Jan van Kessel the elder (1626–1679)

A Cockchafer, Beetle, Woodlice and other Insects, with a Sprig of Auricula

early 1650s

Jan van Kessel the elder (1626–1679)

A versatile painter of still life, including many insects, was Jan van Kessel the elder (1626–1679) whose work includes Various Spiders and Caterpillars, with a Sprig of Gooseberry and A Cockchafer, Beetle, Woodlice and Other Insects, with a Sprig of Auricula.

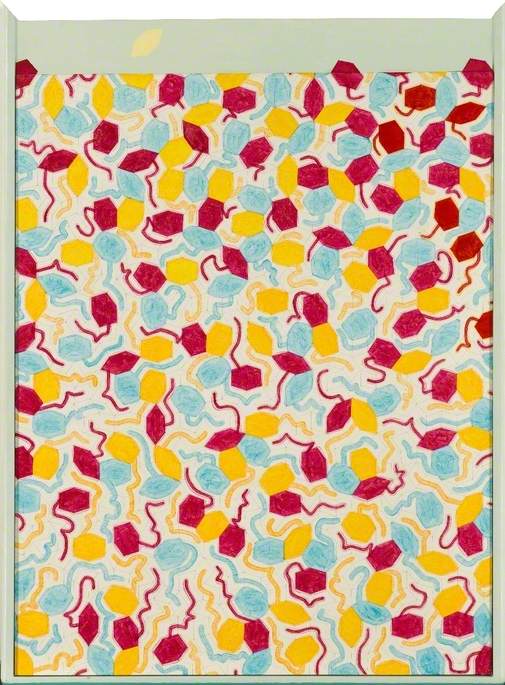

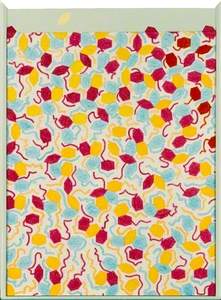

Delving into Art UK helps us to appreciate anew how incredible insects are and shows insects in all stages of formation, from barely yet in being to fully formed (Mosquito Larvae II by Michael Kidner housed in the Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, shows in abstract that early stage in the life of insects).

How insects have haunted the human imagination is clear in The Ghost of a Flea by William Blake. Far from being regarded simply as pests, art shows us that insects are an important part of our world.

As we face the fact of the extinction crisis, it is haunting to realise that some of these paintings may last longer than the glorious creatures themselves and is an urgent reminder to do what we can to save creatures both great and small, whose lives are threatened, before it is too late.

Anita Sethi, journalist, writer and critic