Charles Dickens declared it 'the park par excellence' and drew endless inspiration from it. Created to serve as the private hunting grounds of Henry VIII in 1536, London's Hyde Park has come a long way since, bearing witness to some of the most significant historical events affecting the nation, while providing respite from the bustle of the city for generations of visitors.

It feels improbable now, given its signed and clearly demarcated manicured paths, and its parakeets and geese in their designated spaces, but Hyde Park was once a vast wilderness on the outer edges of what was then the entirety of London.

When Henry VIII acquired the parcel of land from the monks of Westminster Abbey in 1536, he designated it a Royal Park – one of eight in the city – but it remained a private hunting ground. The monarch and his court would often hunt deer in the grounds, in a setting not dissimilar to the one depicted below.

Fallow Deer in Hyde Park, with Kensington Palace

c.1695

British (English) School and Dutch School

Later, when James I ascended to the English throne, limited access was permitted to aristocrats. But it was in 1637, during Charles I's reign, that the park, north of the present Serpentine boathouses, was opened to the public.

At the turn of the eighteenth century, William III moved his court to Kensington Palace. In order to walk through what was seen as a treacherous route to St James's at night, due to the potential presence of highwaymen on horseback, he had oil lamps installed on that stretch of road, and so the first artificially lit highway in England was born.

Originally called the 'Route de Roi', meaning King's Road, the name was later corrupted as 'Rotten Row'. The painting below by Yoshio Markino (1874–1956) depicts a modern view of the path in the evening.

Several decades later, Queen Caroline, consort of George II, carried out renovations to the park and in the 1830s had the Serpentine lake created. While artificial lakes at the time were often long and straight – the kind that would front stately manors – this was one of the first natural-looking artificial lakes. It was received well by the public and the style was subsequently replicated in parks all over the country.

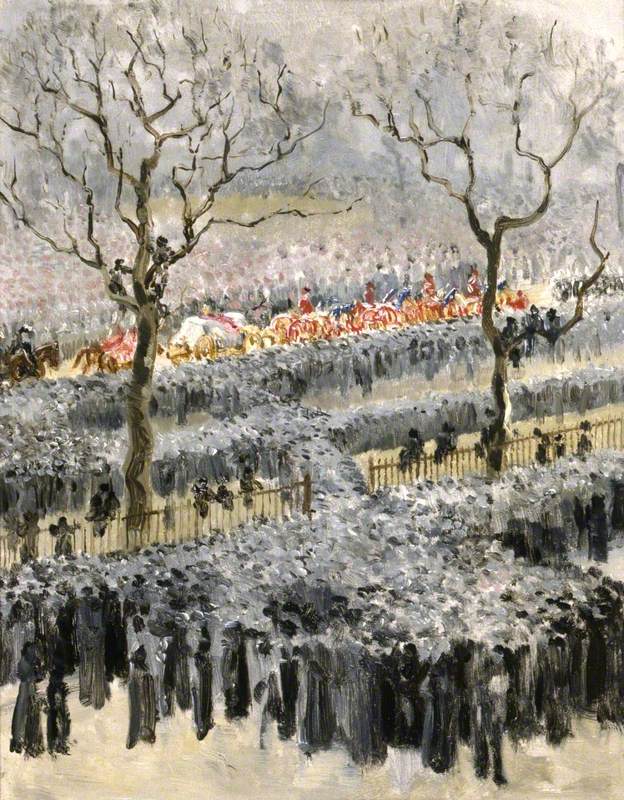

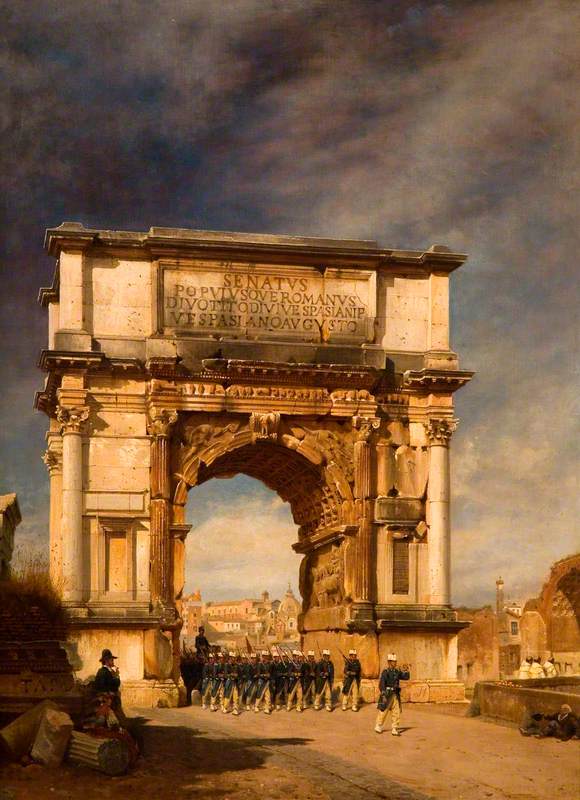

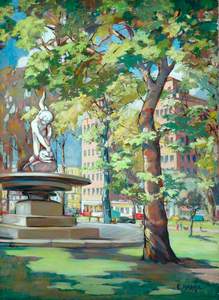

In the century that followed, Hyde Park gradually became an important site for symbolic national celebrations. In 1814, George IV, the Prince Regent, organised fireworks to celebrate the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

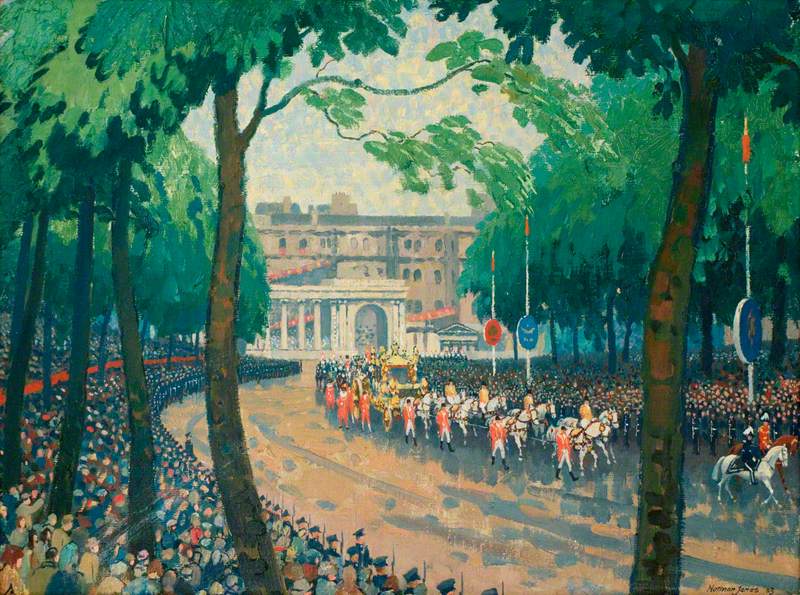

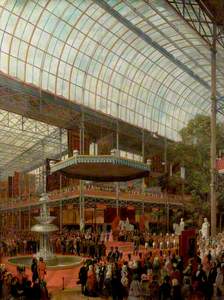

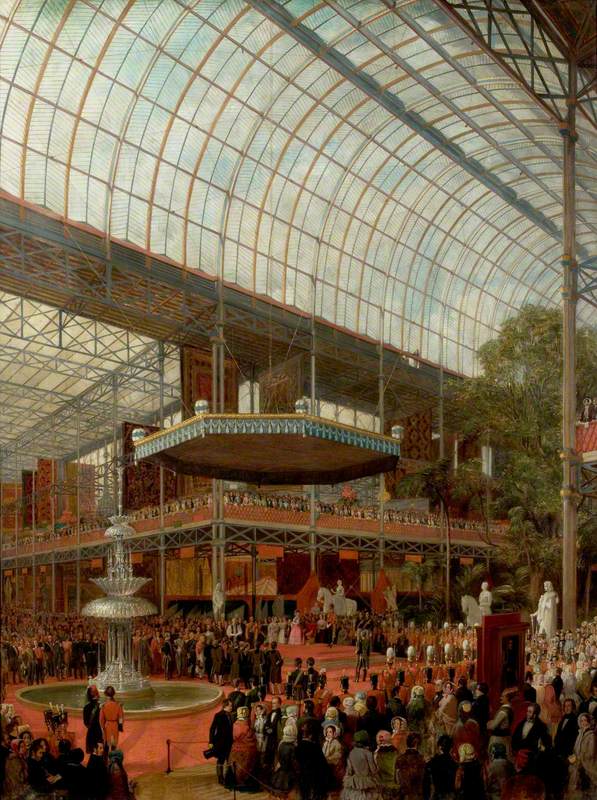

In 1851, the famous Great Exhibition was held during the reign of Queen Victoria, an event for which the Crystal Palace, designed by architect Joseph Paxton, was built. More than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in the famous iron and glass-clad structure to exhibit inventions developed during the Industrial Revolution.

The Opening Ceremony of the Great Exhibition, London

1851

James Digman Wingfield (1800–1872)

Thomas Colman Dibdin's painting of the palace illustrates the vastness of the building that was later moved, piece by piece, to the South London neighbourhood now named after it.

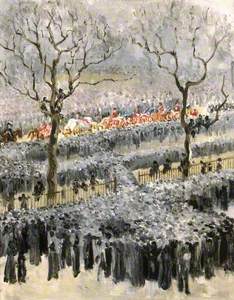

Activities in the park took a decidedly more political turn from 1866, when Edmond Beales led the first Reform League march on Hyde Park to campaign for the representation of the working class in Parliament. Acrimonious fights broke out between the League and the police, but during the second of the League's marches, they were allowed to press on due to their attendees vastly outnumbering the police. This freedom to congregate in the park proved the basis of Speakers' Corner, which since 1872 has become a symbol of free speech.

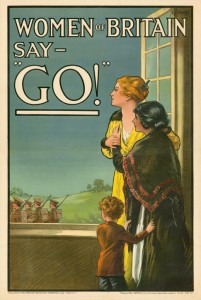

The park proved to be an important endpoint for many subsequent marches for rights, such as Women's Sunday, the march through London which catalysed the Suffragette movement. Christina Broom's photograph of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Christabel and Sylvia Pankhurst and Emily Davison – key members of the Women's Social and Political Union – is now housed in the permanent collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Later, Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, and George Orwell would be just a few of the famous individuals who would grace Speakers' Corner. Orwell, as a frequent visitor and speaker, was fascinated by the diversity of views offered on the platform – from vegetarianism and temperance reform to Communism – and in his essay 'Freedom of the Park' spoke fondly of the candour and civility with which the crowd engaged speakers.

In the turbulent years of the two World Wars, and the period between them, the park returned to its role as a site for leisure activities to lighten the mood of a city that had sustained heavy infrastructural and architectural damage.

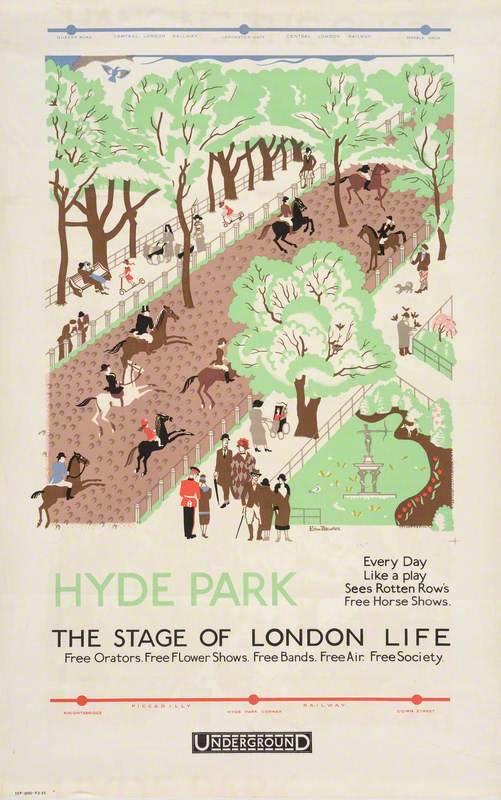

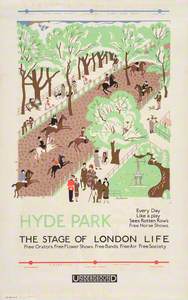

Edward Bawden's poster of Hyde Park advertises the park as a fun-filled family pitstop on London Underground's Piccadilly Line – something that continues to be promoted in the train carriages today.

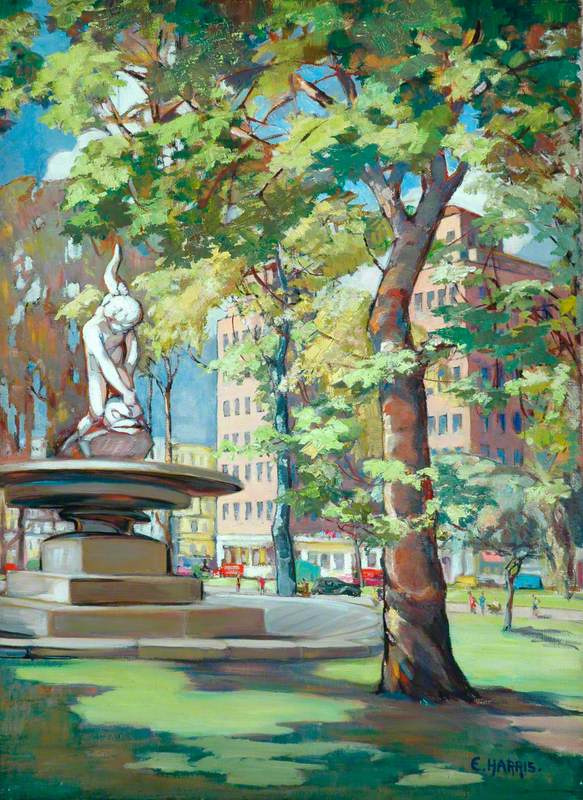

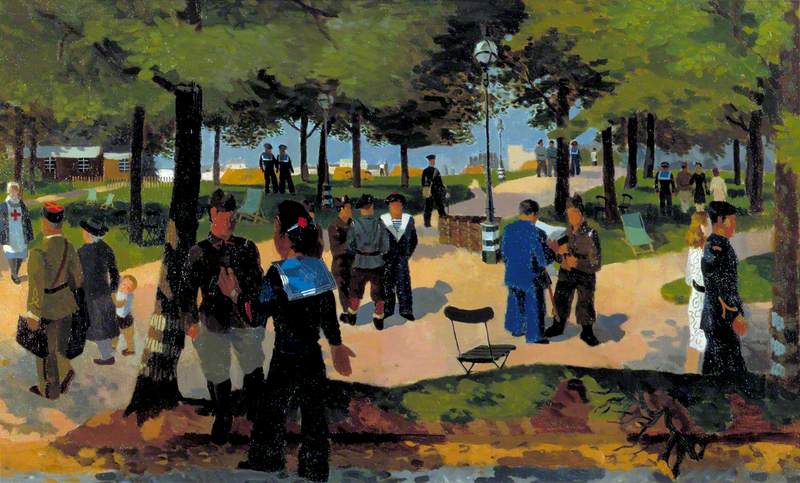

Foreign Servicemen in Hyde Park: Early Summer

1940

Kenneth Rowntree (1915–1997)

During intermittent times of leave during the Second World War, the park was used by many foreign service people for leisure, with military bands playing in the bandstand.

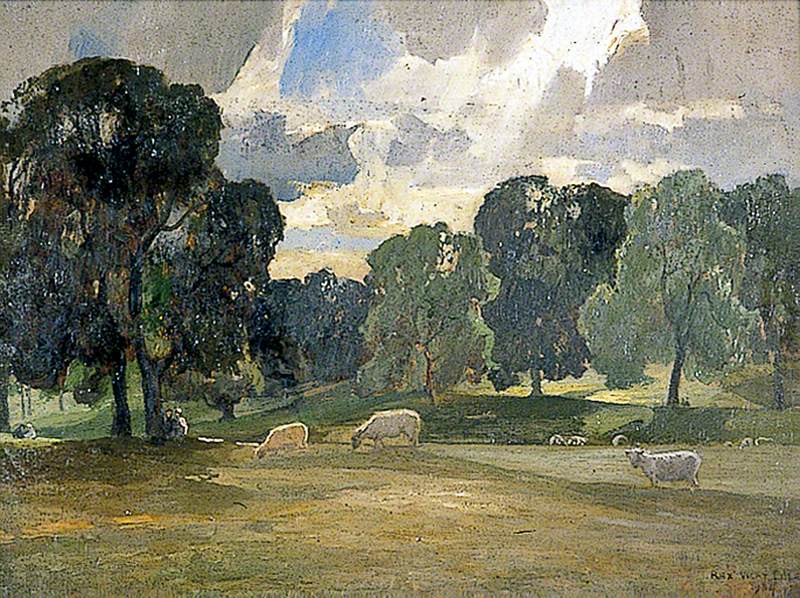

But the park was not always used for entertainment purposes. It proved to be invaluable during wartime efforts for its ability to feed the nation during the period of rationing, with land set aside to grow vegetables as part of Britain's 'Dig for Victory' campaign; the planting of cabbages took over from where the park's ornamental flowers would ordinarily be. The turning of parks into agricultural spaces was not confined to Hyde Park, as shown below in this depiction of the nearby St James's Square during the war.

The AFS Dig for Victory in St James's Square

1942

Adrian Paul Allinson (1890–1959)

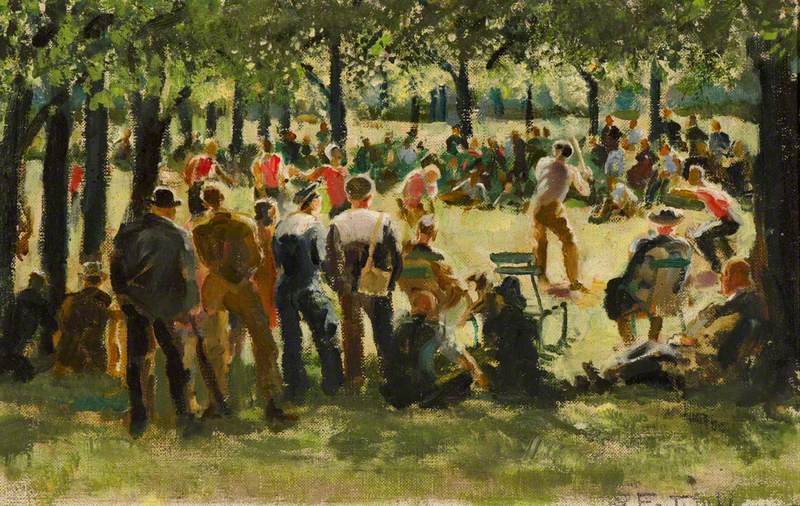

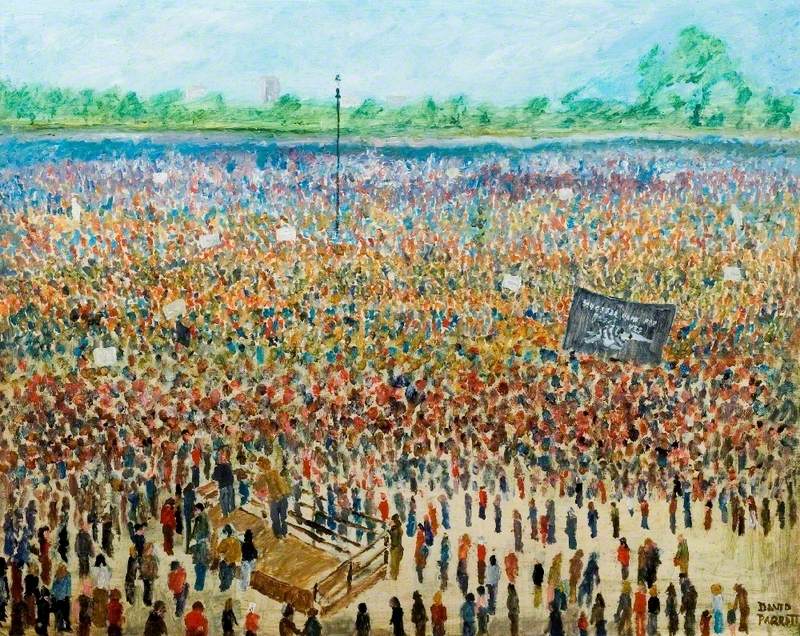

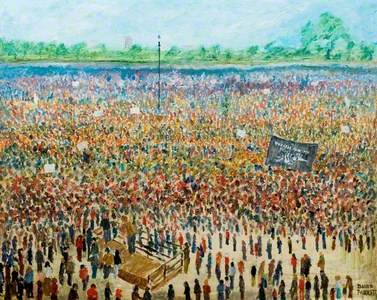

After the war, in the mid-twentieth century, the park drew large crowds attending rallies for peaceful movements. David Parrott's painting depicts a large rally in the first wave of the Campaign For Nuclear Disarmament.

The park was also the site of the anti-war rally in the lead-up to the Iraq War of 2003, which was estimated to have attracted between 750,000 and two million attendees. More recently, marchers defied stay-at-home orders during the first national lockdown of 2020 to protest in support of the Black Lives Matter movement in June, where marchers demanded an end to racism in Britain and abroad.

The perennial nature of Hyde Park as a monument to significant moments in history, through its hosting of activities and demonstrations, cannot be understated. In the age of a global pandemic, as with other times of strife, parks have taken on a renewed significance in our lives as a source of refuge, one where we gather with others. Long may it stay that way.

Ashley Tan, freelance writer