Towards the end of the Second World War, two elderly artists sat in silent companionship in a house in Sussex. It was October 1944 and their careers were behind them, but both had made outstanding contributions to British art.

The older of the two, Sir Frank Short, aged 87, was one of the twentieth century’s most influential printmakers. With just a few months to live, he had been bombed out of his house in London. His 77-year-old companion, Sir Frank Brangwyn, an internationally acclaimed painter, had given Short, and his daughter Dorothea, shelter at ‘The Jointure’, his home in Ditchling.

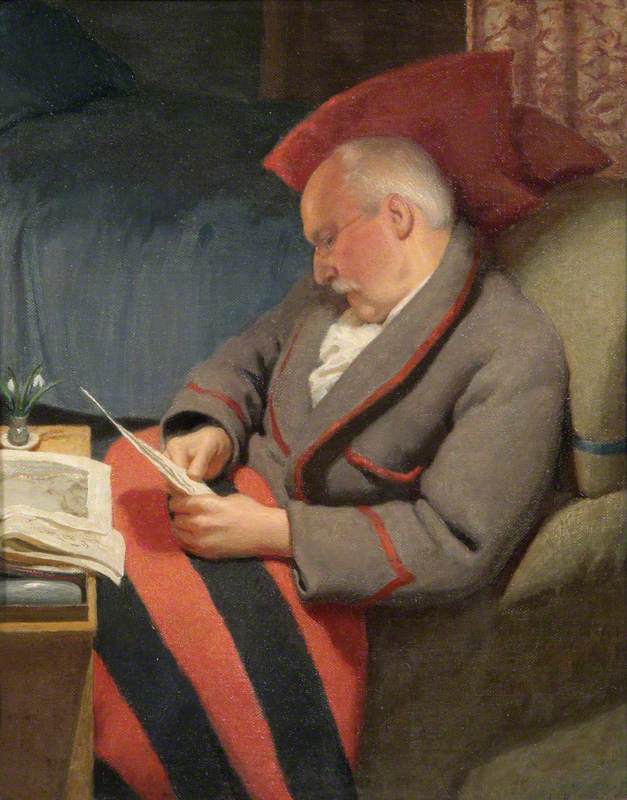

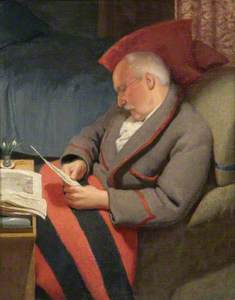

Another artist, the portrait painter John Bulloch Souter, visited the pair in Sussex and captured the former Professor of Engraving in his dressing gown engaged in one of his favourite pastimes – examining prints.

‘He cannot talk or move but is bright and his brain is as clear as ever,’ wrote Brangwyn to his art dealer friend, Matthew Walker. ‘So... in some measure, I hope he is happy.’

Brangwyn had moved to Ditchling during the First World War to escape Zeppelin raids over London. At the time he was a famously prolific artist in a variety of media including paint, print and design, although his career faded in later life.

Short had settled in Sussex in 1924 following his retirement from the Royal College of Art after which he spent less time in London and more at his second home at Seaford. The coastal resort was close enough to Ditchling to renew his friendship with Brangwyn whom he had known since the 1880s when they had neighbouring studios in Chelsea at the start of their careers.

As young men, they had trained together in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve. A drill photograph shows Short, back to the camera, with Brangwyn on the far right.

Short and Brangwyn on a gunnery drill

c.1880, photograph

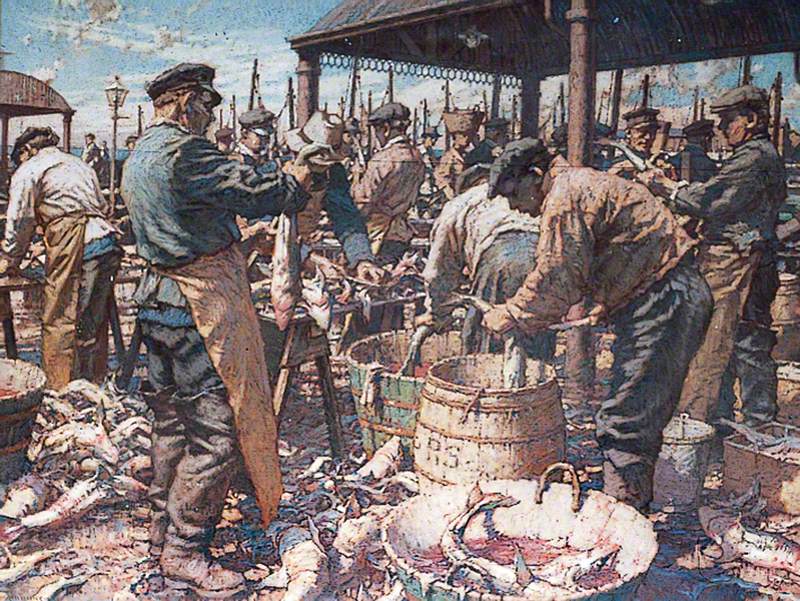

Their shared love of the sea was an important aspect of their friendship and was reflected in their art. Brangwyn painted several seascapes in the 1880s and towards the end of that decade spent more than a year at sea.

On a smaller scale, Short demonstrated his mastery of printmaking in series of etchings and mezzotints around the coast of Newhaven and Seaford.

Some of his atmospheric mezzotints have a distinctly modern feel resembling black and white photography.

The Angry Cloud, Newhaven

1930, mezzotint by Frank Short (1857–1945)

His etchings are also highly skilled, although more conventional.

Rough Weather at Blatchington (Seaford)

1925, etching by Frank Short (1857–1945)

In Sussex, Brangwyn and Short both became widowers in quick succession. Lucy Brangwyn died in 1924 and Short’s wife Esther a year later. Subsequently, the two friends spent more time in each other’s company in both Seaford and Ditchling.

Sir Frank Brangwyn (left) and Sir Frank Short (right) at The Jointure, Ditchling

c.1930, photograph

The 1920s and 1930s were productive decades for both men but, after the outbreak of war, Short had to move following a raid on Seaford.

‘The playful Hun was over the coast here and dropped a bomb on a train which was right in front of Frank Short’s house,’ Brangwyn reported to Matthew Walker.

Short and his daughter moved back to their house in London but were forced out again by persistent German bombing.

It was then that Brangwyn helped out his friend by offering sanctuary at his home in Ditchling. Sadly, Short’s health soon failed and before long Brangwyn was writing to Walker again.

‘No doubt you have seen in the papers that our dear old friend Short has passed away. In the last few weeks of his life he had a lot of pain caused by a clot. I saw him in the two of three days before he passed away poor old dear. So far his girl (Dorothea) bears up very well. It is a great blow to her as she was devoted to him. It was wonderful how she nursed him like a mother with her child.’

After Short’s death, Brangwyn became increasingly reclusive. He died in Ditchling in 1956 at the age of 89.

James Trollope, author and columnist

James's book Short's Sussex explores Sir Frank Short’s lifelong love of the county which inspired more than 50 of his prints. It is available at www.ericslater.co.uk