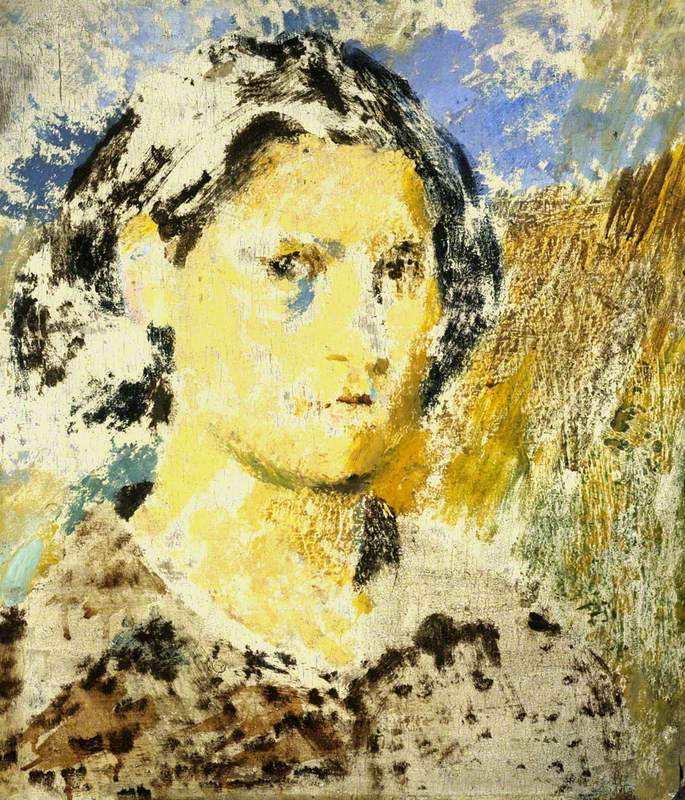

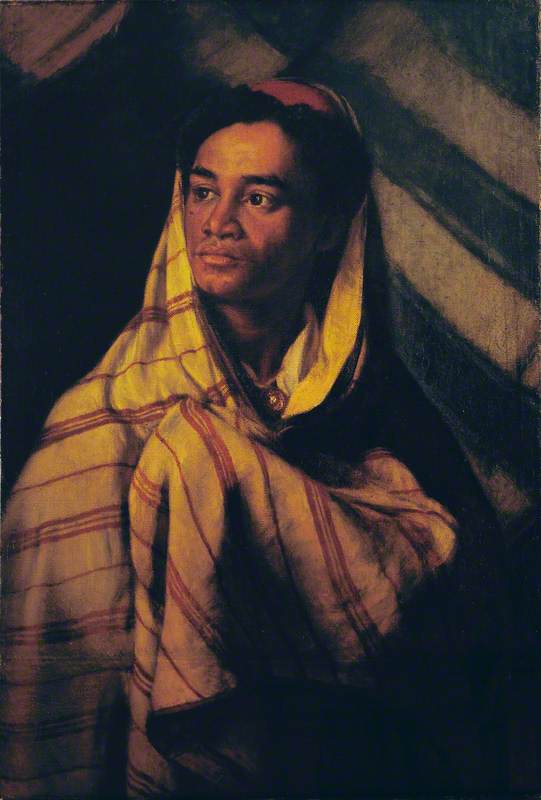

In this picture, the sitter is wearing a metal badge that tells us his name, W. McGregor (he would certainly have been known as Willie), and gives him a number. It thus identifies him as a licensed Edinburgh porter, or caddie (the Scots word now adopted in golf).

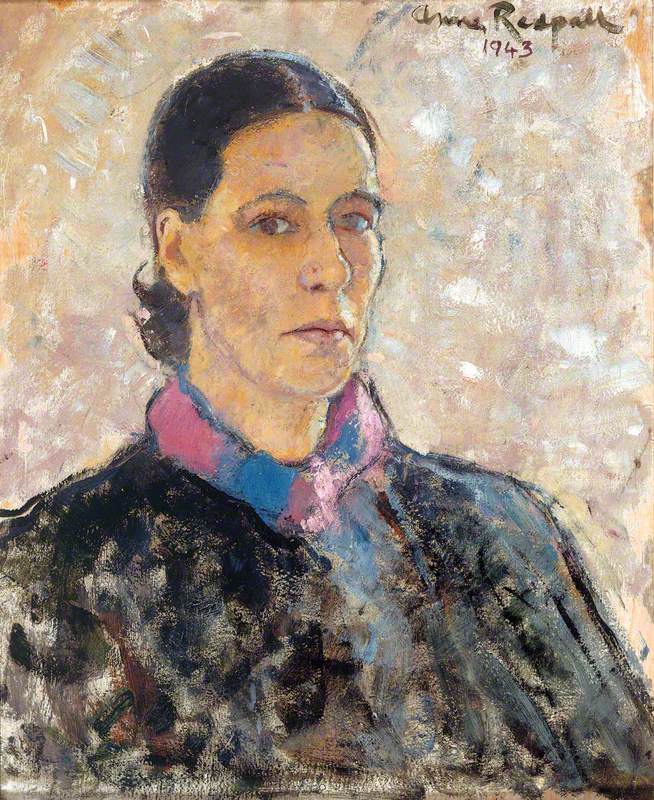

William MacGregor, an Edinburgh Porter

James Cumming (1732–1793) (attributed to)

For reasons set out below, the picture probably dates from the 1770s and was most likely painted by James Cumming. Cumming was a close friend of the artist Alexander Runciman. They had been apprentices together in the Norie firm of Edinburgh painters and decorators. There are several decorative schemes by James Norie extant. One at Haddo House, for instance, is particularly striking.

Landscape with a River and a Building*

James Norie (1684–1757)

Runciman's self-portrait with another artist friend, John Brown, is in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and gives an idea of his vivid personality.

John Brown (1749–1787), Artist, with Alexander Runciman (1736–1785), Artist

1784

Alexander Runciman (1736–1785)

He and Cumming both belonged to the Cape Club. With a lively membership that included actors, painters, poets and musicians, the Cape moved peripatetically around the Edinburgh taverns drinking a lot of porter, not claret like the posher folk, and talking excitedly about all the latest ideas. If it was not an anachronism, you could call them bohemians, a riff-raff intelligentsia without the wealth and security of their better-known Enlightenment contemporaries.

They were also patriotic Scots, though by no means parochial. In 1771 Alexander Runciman had, for instance, returned to Edinburgh after four years in Rome.

In the eighteenth century, porters like Willie McGregor were mostly Gaelic-speaking Highlanders. The City Guards – in modern terms the police – were Highlanders too.

Robert Fergusson (1750–1774), Poet

c.1772

Alexander Runciman (1736–1785)

In his poem Leith Races, Robert Fergusson, also a member of the Cape Club and whose portrait Runciman painted, clearly identifies the Guards as Gaels when he writes: 'Their 'stumps erst us'd to filipegs/Are dight in spatterdashes'. [Their legs, once used to kilts, are clothed in gaiters.]

A much later painting by Mary Cameron shows a man dressed in a City Guardsman's uniform.

What he is carrying is probably a nineteenth-century ceremonial halberd. The eighteenth-century guardsman's Lochaber axe was more utilitarian. As well as an axe blade, it was fitted with a hook with which miscreants could be grabbed and apprehended.

In the same poem, Fergusson mimics the Guards' Highland accents and quaint English. As well as his identity as a porter, Willie McGregor had a Highland name, so we can be pretty sure that he was Gaelic speaking.

He is also painted with his mouth partly open and his teeth visible. This is highly unusual in a portrait. Smiling portraits showing teeth only became fashionable with the snapshot camera, so the painter here has evidently shown his sitter's mouth open on purpose. Almost certainly it is because Willie McGregor is singing: he is a singing Gael.

Folk song and oral tradition were hot topics. In the 1770s Robert Burns had not yet started collecting songs, but already in 1769 an earlier collector, David Herd, had published his first collection of Scots songs. Herd was also a member of the Cape Club and was a close friend of Runciman and Cumming. It was, in turn, Herd and Cumming who put up Robert Fergusson for membership of the club.

Gaelic song was as much of interest to these musical pioneers as was Scots song. Indeed, the Gaelic oral tradition was even more topical for in 1760 James Macpherson had published Fragments of Ancient Poetry Collected in the Highlands of Scotland and Translated from the Gallic or Erse Language.

James 'Ossian' Macpherson (1736–1796), MP

1772

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

This, and his subsequent publications of Ossianic verse, collected together and always known simply as Ossian, caused immense excitement, not only in Edinburgh but right across Europe. The claim was that, preserved by oral tradition, this body of verse had survived from earliest times in the remote glens of Scotland.

The exact status of Ossian need not detain us here. What Macpherson published did have a basis in genuine oral tradition, but, true or false, the claim of antiquity, that this was the voice of ancient Caledonia – a nation never subject to the Roman yoke and whose poetry and song were therefore free from all the stifling burden of the classical tradition – was immensely exciting.

One of the earliest and most vivid responses was the painting in 1772 of Ossian's Hall in Penicuik House by Alexander Runciman. Sadly destroyed in a fire in 1899, the ceiling of this very large room, the saloon or drawing room of the house, was painted with scenes from Ossian's poetry in a rapid and brilliant style. His oil sketch design for the central oval is in the collection of National Galleries Scotland.

Took the opportunity (while being in laptop limbo) of viewing 'Wild and Magestic' @NtlMuseumsScot. Some fascinating objects on show; Runciman's Ossian design for Penicuik House, gown decorated with beetle wings, medievalesque helmet and crest of Atholl, stags teeth jewellery... pic.twitter.com/KPBPz3mEKJ

— Dr Bryony Coombs (@BryonyCoombs) August 27, 2019

It matched the qualities identified with Ossian exactly as Hugh Blair, professor at Edinburgh University and Macpherson's champion, described them: 'Irregular and unpolished we may expect the productions of uncultivated ages to be; but abounding, at the same time with that enthusiasm, that vehemence and fire, which are the soul of poetry.' With his hair and neckerchief blowing in the wind, Willie McGregor is very much in the character of Runciman's Ossian and so is presented as a living witness to the same oral tradition of Gaelic poetry and song.

Perhaps because the later controversy about its authenticity discredited Macpherson's Ossian here, after Runciman's great work there are relatively few Ossianic subjects by British painters. William Brockedon's Ossian Relating the Fate of Oscar to Malvina (in Totnes Guildhall) is an exception.

In France, however, Ossian was a favourite of Napoleon and Ossianic subjects became highly fashionable. This fashion could hardly have crossed the Channel during the Napoleonic wars, however, and Anne-Louis Girodet's painting of Malvina Mourning the Death of her Fiancé Oscar (National Galleries Scotland) is a unique example of a French painting with an Ossianic subject in a British public collection.

Malvina Mourning the Death of her Fiancé Oscar

c.1800

Anne-Louis Girodet de Roucy-Trioson (1767–1824)

Although Willie McGregor's portrait is quite like work by Alexander Runciman, it is not by him. We can see that from comparison with his known works.

Drawings and etchings by Runciman related to Ossian's Hall are all that survive of his work there, but the National Gallery of Scotland has a number of paintings by him including The Death of Dido and Agrippina Landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus.

Agrippina Landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus

1781

Alexander Runciman (1736–1785)

The painting is, however, close enough to Runciman's style to be by someone associated with him – as we know Cumming was. There are no paintings known that are certainly by Cumming, but many years ago I did see two pictures signed by him in a saleroom. They were closely comparable to this picture.

There are other things, too, that help confirm that identification. The picture was clearly painted by an Ossian enthusiast and one who was familiar with the street life of Edinburgh. We know from his letters that James Cumming was passionate about Ossian and his and Alexander Runciman's friend, Robert Fergusson, was the poet par excellence of the clarty street life of Edinburgh, of Auld Reekie, the city's familiar name and also the title of a long poem by Fergusson. Indeed, Cumming may have helped persuade Runciman to choose Ossian for the Penicuik ceiling. If that is so, then it also suggests a date near that of the ceiling, 1772.

So, identified by James Cumming as a living Ossian, across nearly two and half centuries Willie McGregor still sings for us his Gaelic songs.

Duncan Macmillan, art critic and art historian