New towns in Scotland, as in the rest of the UK, have had to withstand a certain amount of mockery from the media since their inception in 1946.

From their beginnings in earnest post-war reconstruction, the five towns – East Kilbride, Glenrothes, Cumbernauld, Livingston and Irvine – came to represent a modernist intent that unsettled the traditionalism with which the British establishment asserted both control and a sense of belonging.

Ex Terra

1965, outdoor sculpture at Glenrothes bus station by Benno Schotz (1891–1984)

The towns grew swiftly, attracting those keen to flee overcrowded and dilapidated slum housing in Glasgow and begin afresh in clean modern homes with green and spacious surroundings. Alongside these benefits, there were also issues around how some residents might struggle to adapt to their new environments.

The new town planners and architects had tight schedules and limited budgets, which sometimes resulted in harsh and repetitive townscapes. These needed humanising and visual relief if they were to approach the utopian ideals to which the new town development corporations aspired. The answer: employing town artists.

Sculpture Group

1967, outdoor sculpture in East Kilbride by Jim Barclay

If the town artists were to provide a sense of identity for these new places and communities, they needed to adopt an approach that responded to the town environment. The traditional urban public sculpture of monuments, statues, memorials and elevated works on plinths was out of step with the modern vision of these new towns; something different was required.

If it can be argued that public sculpture changed the five new towns in Scotland, then it follows that the new towns changed approaches to public sculpture.

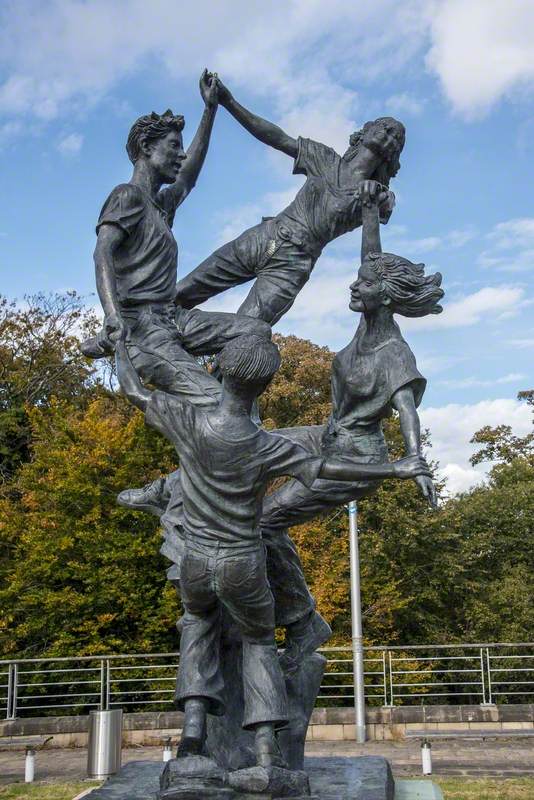

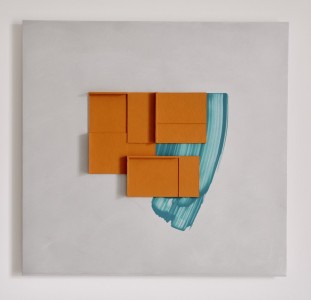

Unity

1970, outdoor sculpture in Livingston by John H. White

Collaborations between artists and architects had historically enjoyed periods of popularity, and a resurgence that began in London and its satellite new towns drifted northward to reach Cumbernauld, Scotland's most architecturally spectacular new town, where, in 1962, Brian Miller became the pioneer 'town artist' north of the border.

Showpiece new town centres acted as a focus, and featured provocative modern buildings and layouts, with accompanying artworks and decorative elements. Planners recognised that there was also a place for art where people lived, and engaged artists to push art outwards into residential communities.

Miller's Carbrain Totem (1966) in Cumbernauld is a quintessential new town sculpture: concrete, and constructed by the artist working in collaboration with engineers and labourers, its abstract form inviting imaginative engagement from residents.

Although Miller worked at Cumbernauld for almost three decades, sadly little else remains of his large output, many other works having fallen victim to changing tastes and redevelopment.

His influence has endured through the confidence he inspired in others that there was a place for the artist in town planning departments. When Glenrothes advertised for an artist, Miller advised a more integrated role than he himself had experienced at Cumbernauld.

Henge

1970, outdoor sculpture in Glenrothes by David Harding (b.1937)

David Harding – the town artist in Glenrothes from 1968 to 1978 – observed what Miller had begun, and gradually developed his own experimental conceptual practice.

He quickly learned how to work within the hierarchy of the development corporation by engaging colleagues at all levels to assist in realising projects. He worked with architects, construction workers and the community, and their input was seen as being of equal value to that of the artist. This way of working brought people together through collaboration.

Harding's work reflected on the history of Glenrothes, both ancient and more recent in works such as Henge (1970), which combines elements of prehistoric earthwork and Pictish symbolism with references to a roster of twentieth-century figures such as Gandhi, Che Guevara, Bob Dylan and The Beatles.

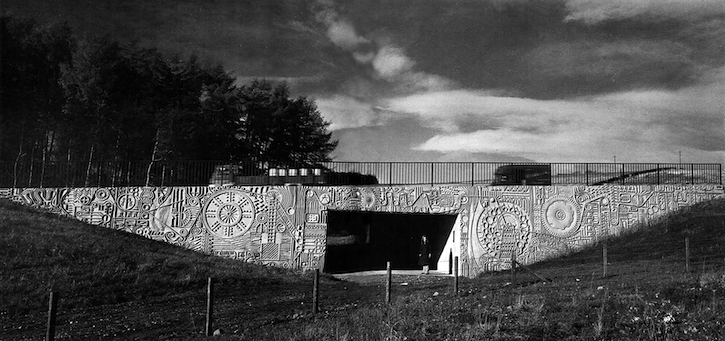

Industry

1970, outdoor sculpture in Glenrothes by David Harding (b.1937)

Industry (1970), which shows elements of past and present regional commerce, is one of several pedestrian underpasses for which Harding created external concrete murals.

Together with his many works around paths and walkways, these sculptures show the artist's desire to provide art for the local residents on foot, rather than 'roundabout art' for passing traffic. (Though, given the quantity of roundabouts in new towns, some identifying markers are desirable!)

Hippo Group

1973, outdoor sculpture in Glenrothes by David Harding (b.1937) and Stanley Bonnar (b.1948)

Harding also employed recent art graduates as assistants, allowing them to collaborate and develop their own work as their skills and confidence grew.

His first assistant, Stanley Bonnar, created the famous concrete Hippo, the first 'multiple' new town sculpture, which Harding and Bonnar positioned in groups around Glenrothes on sites of meaning or surreal whimsy.

The Birds

1980, outdoor sculpture in Glenrothes by Malcolm Robertson (b.1951)

Harding left Glenrothes to pursue a career in education, and went on to found the department of environmental art at Glasgow School of Art. The town artist role went to Malcolm Robertson, who continued to work in residential areas, and added landmark pieces such as The Birds (1980) and Giant Irises, the town's contribution to the 1988 Glasgow Garden Festival.

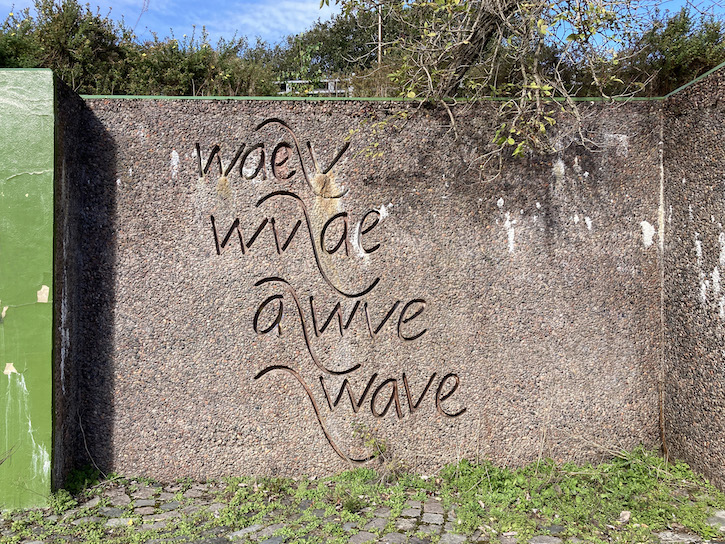

Wave Wall

1976, outdoor artwork in Livingston by Denis Barns and Ian Hamilton Finlay (1925–2006)

Denis Barns, who was the town artist in Livingston from 1974 to 1978, operated in a similar manner, learning how to make sculpture with no obvious materials budget, and initiating major collaborative projects such as Wave Wall (1976), which integrates the poetry of Ian Hamilton Finlay into the concrete infrastructure of a pedestrian walkway.

The Old Men of Hoy

1976, outdoor sculpture in Livingston by Denis Barns

In turn, this forms part of a series of interlinked works around Livingston's riverside, part of a developing practice that emphasised integration of art and design, including The Old Men of Hoy (1976), a cluster of coloured concrete monoliths that serve as sculpture but also break up the water flow into the River Almond.

Like Miller, Barns saw his most lasting achievement not in his own artistic works but in creating a place for art within the new town environment – art the community could engage with and call their own.

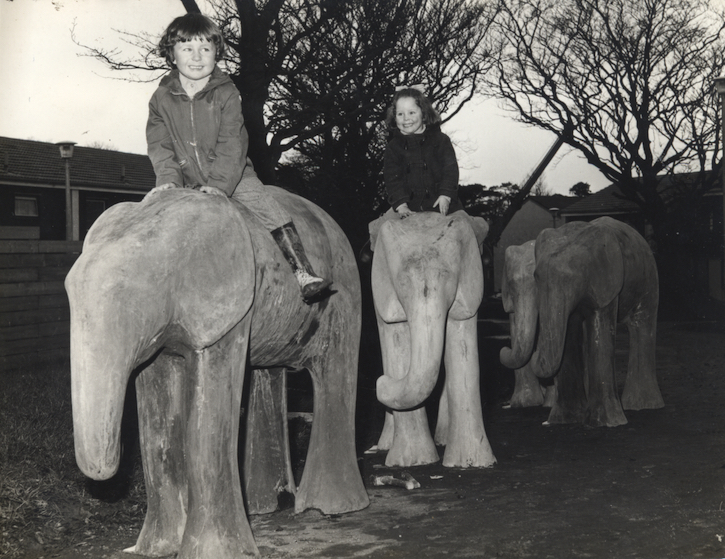

Elephants

1974, outdoor sculpture in East Kilbride by Stanley Bonnar (b.1948)

Stan Bonnar and J. Keith Donnelly, another former assistant to David Harding in Glenrothes, rose to become consecutive town artists at East Kilbride, creating and commissioning work to provide a sense of identity for a new town that was keen to avoid domination by nearby Glasgow.

Bonnar departed the role following the demise of the Stonehouse new town project, but not before installing a small troupe of concrete elephants there. Stonehouse had been planned as Scotland's sixth new town, but the development was halted only days after the first residents moved in.

Monarch

c.1994, outdoor sculpture in East Kilbride by J. Keith Donnelly

Donnelly saw his role develop into commissioning activity as Environmental Art Officer, enabling other artists to create a more varied visual environment, though perhaps lacking the cohesive identity provided by a long-term placement.

All At Sea

1990, outdoor sculpture in Irvine by Mary Bourne (b.1963)

In Irvine, the last of the new towns to be developed in Scotland, the development corporation chose not to appoint a town artist. Instead, from 1979 to 1989 they provided a series of artist residencies in conjunction with the Scottish Arts Council, reflecting a move away from long-term engagements.

Although the artists moved on, their works endure. Mary Bourne's sculpture All At Sea (1990), which was originally sited on a shingle spit, had to be relocated to Irvine's harbour walkway when its position became threatened by coastal erosion.

Celtic Dragon

1987, outdoor sculpture in Irvine by Anthony Vogt and Roy Fitzsimmons

In 1987, Anthony Vogt and Roy Fitzsimmons won the Arts Council's 'Art into Landscape' competition with their proposal to construct Celtic Dragon from the remnants of a disused railway bridge. The work still sits above the dunes in Irvine Beach Park, part of the Irvine Bay Regeneration project.

Trinity Mirror

2013, outdoor sculpture in Irvine by Peter McCaughey (b.1964)

Regeneration was also the force behind Peter McCaughey's nine-metre-tall Trinity Mirror (2013), which he developed as a focal point for the transformed Bridgegate area in Irvine, featuring a clever interplay of mirror and text.

The second generation of town artists diversified and adapted to changing times, as the fortunes of new towns greatly diminished under successive Tory governments, and commissioned work slowly came to dominate artistic additions to the towns. Such works can nevertheless be revealing.

Bill Scott's The Shopper (1981) encapsulates the importance of commerce, the waning of abstraction, reduced to a subsidiary backdrop, and the primacy of representation and sentimentality.

These are themes shared by Malcolm Robertson's Shoppers (1988) in Glenrothes Kingdom shopping centre. Populism replaced challenge, artist and community still meeting eye-to-eye but on a less provocative level.

Michael Snowden's Mother and Child (1980) is perhaps a rather late entry on a theme popularised by Henry Moore, with related examples in Basildon (by Maurice Lambert, 1962), Stevenage (by Franta Belsky, 1958) and at the earlier modern Prestonfield Primary School in Edinburgh (by Tom Whalen, 1935).

These celebrate the fecundity of new towns, although by the 1980s – with the high birth rate in the first decades of the new towns and a fragmentation of the traditional family unit – the subject could also be interpreted as single parenthood.

Another later commissioned work, Charles Anderson's The Community (1996), shows new town art debased as reductive symbolism, a performance of community rather than an active engagement of an audience. Here bronze children are mounted on a plinth, where once real children could clamber up David Harding's Rocket (1973).

Rocket

1973, outdoor sculpture in Glenrothes by David Harding (b.1937)

Would we have The Kelpies, Andy Scott's 2015 sculpture in Falkirk, without Stan Bonnar's Hippos in Glenrothes more than 40 years earlier?

Certainly, there has been a move away from the intimate and contextualised work of the town artists towards a more dramatic statement, but the projection of civic ambition should not neglect the new town heritage in favour of a return to monumentalism. Perhaps celebration of the recent past can suggest alternative futures?

New towns have a special history, and an artistic heritage that is gaining wider acknowledgement and respect. Its conservation is necessary for future generations of residents to enjoy, and for artists and commissioning bodies to gain a greater understanding of what artists can offer communities through long-term placements.

Andrew Demetrius, curator, researcher and artist

This content was supported by Creative Scotland

Further reading

Jeremy Howard and Andrew Demetrius, The Enduring Town Art of Glenrothes, University of St Andrews, 2018

Meet You at the Hippos will be broadcast on BBC Scotland and available on BBC iPlayer from 30th November 2021