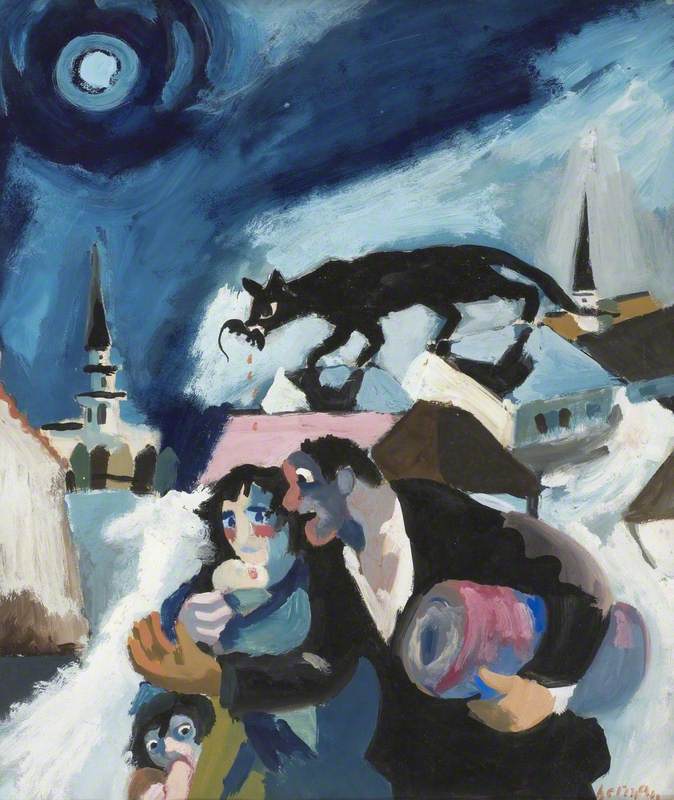

'I was drawn to depict all I could remember [of Jewish life in Warsaw] as faithfully as a chronicler, though always in colours and scenes that expressed my own nostalgia for a vanishing past and a deep sense of sympathy for the millions of Jews who had remained in Eastern Europe and who were being systematically starved, humiliated and extinguished… I walked the streets of the Scottish city [Glasgow] and all I could see was what my memory wanted me to see, a fabric of distant life, which was nonetheless part of me.'

– Josef Herman

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, a steady stream of Jews flowed into and through Scotland. Many continued west to the USA, but a significant number stayed. This migration brought numerous Jewish artists to Scotland, culminating in a series of exhibitions from 1939 to 1951 organised by or featuring Jewish artists in the country. These exhibitions mark a high point of Jewish artistic influence in Scotland.

The first big wave of migration of Jews to Scotland was prompted by poverty and antisemitism in the wider Russian Empire. This included pogroms (violent riots), the 'May Laws' of 1882 (which severely constricted Jewish activity in the Pale of Settlement) and, in 1891, the exclusion of Jews from numerous Russian towns and cities, including Moscow. Journalist Chaim Bermant has estimated that between 1881 and 1930, four million Jews emigrated from eastern Europe (a third of the region's Jewish population) – around 210,000 of whom ended up in Britain.

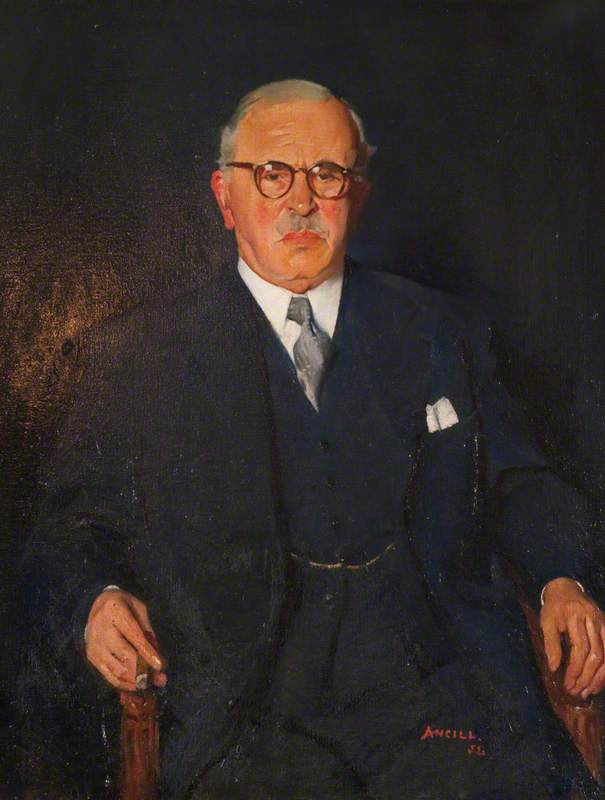

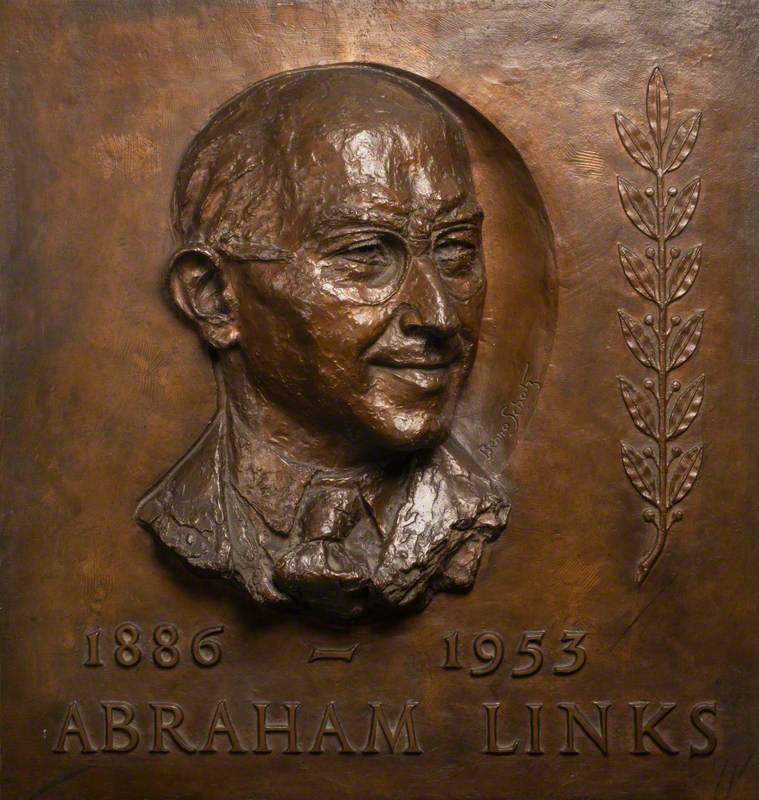

Among the earliest immigrants in this wave were the parents of Scottie Wilson (born in Glasgow in 1891), Joseph Ancill (born in Leeds in 1896, later moving to Glasgow) and Paul Jeffay (born Saul Yaffie in Glasgow in 1898), all of whom went on to become artists either in Scotland or elsewhere. A little later came the father of artist Hannah Frank (born in Glasgow in 1908), who left Lithuania in 1905, and Benno Schotz, who moved from Estonia in 1912 to study engineering in Glasgow.

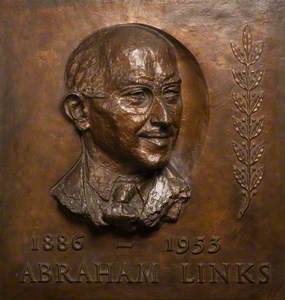

Without the crystalising effect of first-hand experience of the Second World War or the Holocaust during their formative years, the artistic practices of Schotz and Frank were not defined by their Jewishness. As a proud Jew and committed Zionist, Schotz's portrait busts included Israeli prime ministers David Ben-Gurion and Golda Meir as well as prominent Jewish figures in Glasgow such as Ernest Greenhill and Abraham Links.

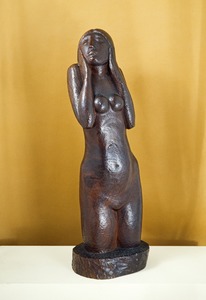

However, Schotz was also enormously proud of his Scottish home. He did not limit himself to Jewish subjects, and his sculptures cannot be described as inherently 'Jewish'. He sculpted numerous Christian and non-Jewish Scottish subjects, and almost nothing dealing directly, or even indirectly, with the Holocaust. Indeed, he produced little work at all during the war (aside from The Lament, 1943), saying it had a 'numbing effect' on him.

Schotz held numerous prominent positions in the Scottish art world throughout his career, including Head of Sculpture at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA). He was even appointed the Queen's Sculptor-in-Ordinary in Scotland in 1963. While his art may not have been inherently Jewish, his influential position allowed him to promote Jewish art and influence Scottish art in other ways.

Two Allegorical Figures, Armorial Shield and Decorative Reliefs

1929–1931

Benno Schotz (1891–1984) and Andrew Graham Henderson (1882–1963)

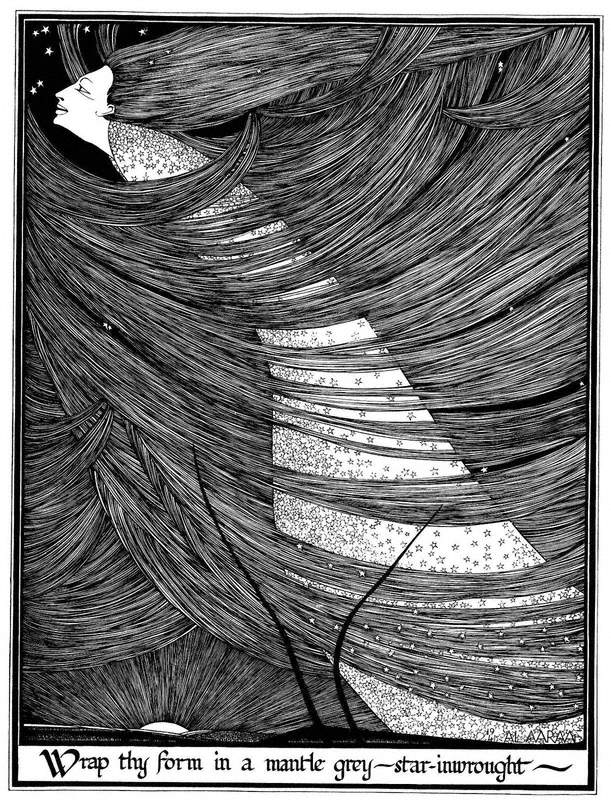

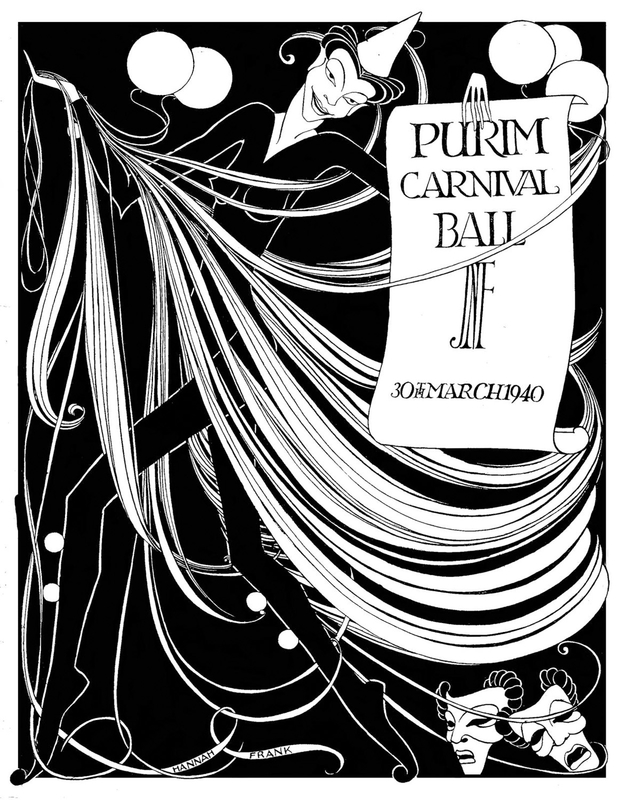

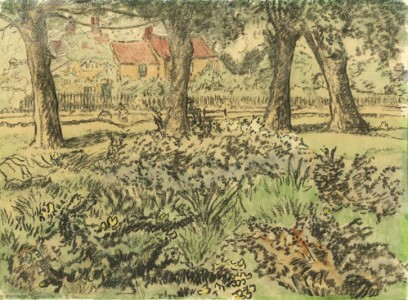

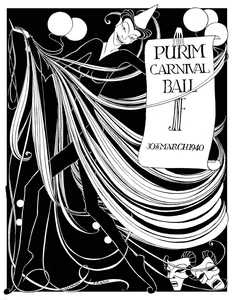

For Hannah Frank, the British and wider European literary canon was more influential on her work than her Jewishness. This is not to say that her Jewishness was unimportant to her; her mother's orthodox parents ran a kosher oil shop in the Gorbals and Frank was a member of numerous Jewish and Zionist societies during her time at the University of Glasgow.

In spite of this, Frank's Romantic, Art Nouveau drawings owe more to Shakespeare, Burns and the Glasgow School than her Jewish heritage. She was as likely to be inspired by Percy Shelley or George Meredith as the Torah or Jewish festivals. Perhaps this should be no surprise for an artist born in the city of Margaret MacDonald and Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

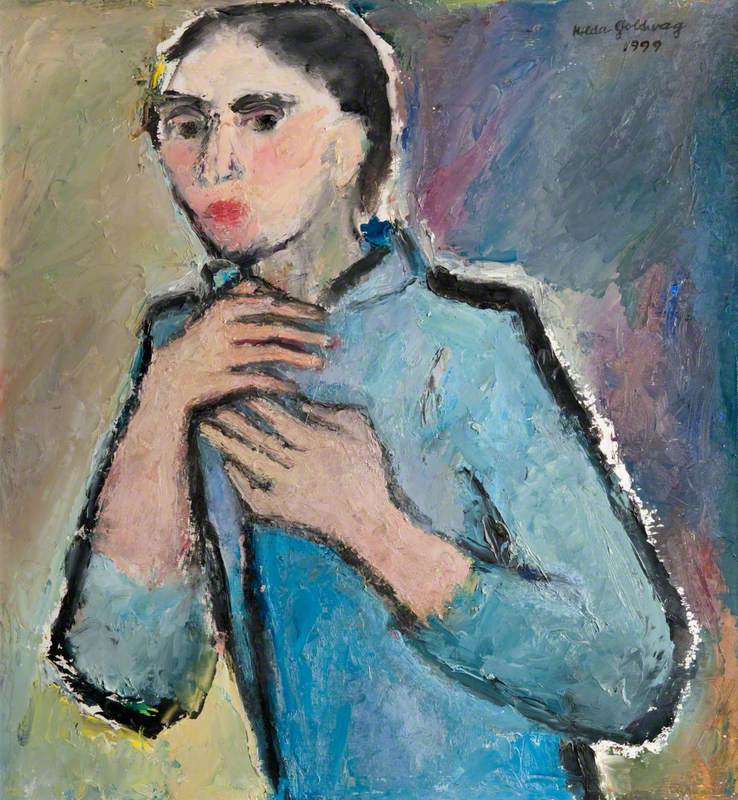

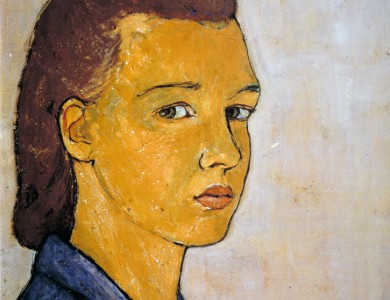

The rise of Nazism prompted a second big wave of Jewish migration, as Jews fled the antisemitic laws increasingly enacted throughout the 1930s in Germany and other countries under Nazi control. Edith Simon left Germany for England in the face of rising persecution in 1932, eventually settling in Edinburgh in 1947. Fellow artists Paul Zunterstein and Hilda Goldwag left Austria after the German annexation of the country, arriving in Scotland in 1938 and 1939 respectively.

Their first-hand experience of Nazism and the guilt of escaping the fate of their Jewish friends and family coloured the work of these artists. Simon's left-wing politics and artistic practice, for instance, were undoubtedly driven by her first-hand experience of fascism.

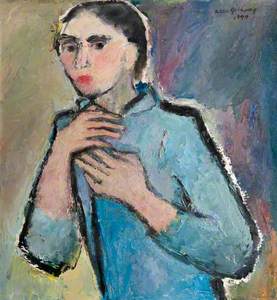

Goldwag was even more deeply marked by her narrow escape from Austria. She managed to obtain a permit to reach Edinburgh in March 1939 thanks to the wife of prominent German-Jewish physicist Max Born. Fatally, the permits for her family (mother, brother, sister, brother-in-law and eight-year-old nephew) arrived on 3rd September, two days after Germany invaded Poland and too late for them to escape. They all perished in the Holocaust, probably at Dachau concentration camp.

For Goldwag, this was devastating. The fate of her family (and the wider Jewish population) weighed heavily on her, resulting in frequently melancholic works painted in subdued tones. She often chose to focus on images of decay: broken machinery, abandoned shopping trolleys, rotting boats. Even the street scenes of her adopted home of Glasgow – a city that was so important to her life and art – are usually bleakly devoid of people.

Goldwag's paintings were not uniformly marked by her experiences – her tender portraits of companion Cecile Schwarzschild are an example of more joyful expression – but she thought and dreamt about her family and the 'evil… visited on them' for the rest of her life.

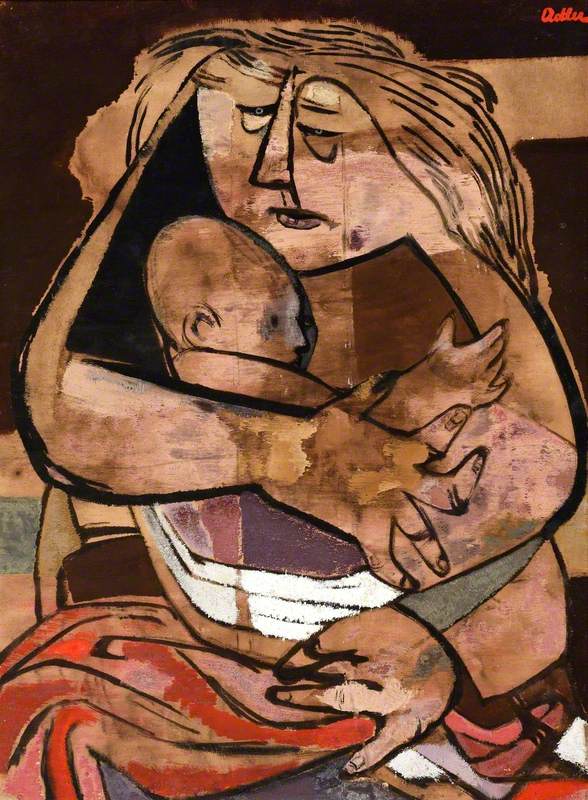

Artists displaced by the outbreak of the Second World War also made their way to Scotland. Jankel Adler joined the Polish army, was evacuated from France shortly after Dunkirk and reached Glasgow in 1940. Josef Herman also arrived in Glasgow in 1940 after escaping the Nazi invasion of Belgium.

Adler and Herman's arrival came soon after Benno Schotz (who had been appointed head of sculpture at the GSA in 1938) had helped bring the influential 'Twentieth-Century German Art' exhibition to Glasgow from London in 1939. This exhibition had been put on in direct response to the 'Degenerate Art Exhibition' staged by the Nazi Party in 1937 and included several Jewish artists such as Max Liebermann and El Lissitzky. Perhaps more crucially, it helped expose Scottish artists directly to German Expressionism.

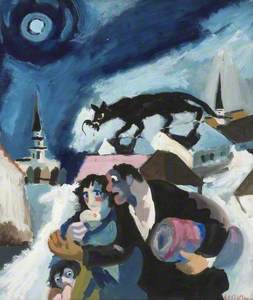

For Adler and Herman, Jewishness, and particularly their first-hand experience of war and persecution as a result of their Jewishness, strongly influenced their style and subject matter. As the quote at the beginning of this story demonstrates, Herman's art remained haunted by his nostalgia for the vanished past. Adler's paintings are full of bleak, semi-geometric compositions or portray the victims of war.

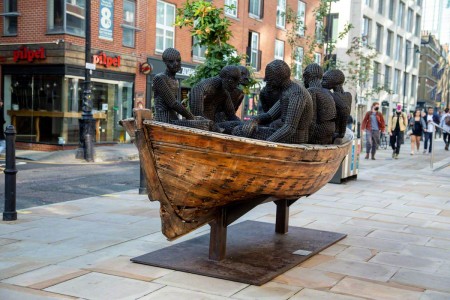

Schotz helped both Adler and Herman put on solo shows in the city in 1941, allowing a generation of Scottish artists to experience Eastern European Jewish art first-hand. In 1942, Herman and Schotz worked together to put on an exhibition of Jewish art at the Jewish Institute in the Gorbals. This featured some of the most important and influential European artists of the twentieth century, including Amedeo Modigliani, Marc Chagall, Ossip Zadkine, David Bomberg and Chaïm Soutine. Zadkine's Music Group was purchased for the Kelvingrove Art Gallery as a result of the exhibition. Nine years later, Schotz organised a Festival of Jewish Art as part of the 1951 Festival of Britain.

The Music Group

(Concerto ou les musiciennes) 1927

Ossip Zadkine (1890–1967) and Grandhoe Andro (active 1927)

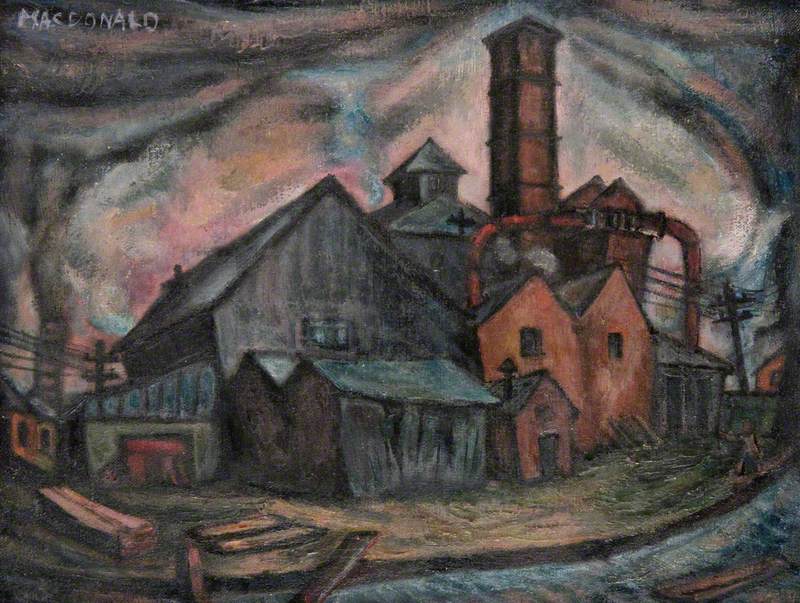

With all this artistic activity, predominately driven by Jews, it is perhaps no surprise that Scottish painter Tom Macdonald has stated: 'Glasgow was indeed lucky that these "refugees" came to the city and stayed long enough to open windows for the less experienced.'

The list of those influenced by these 'refugees' is a long one. Macdonald himself, Willison Taylor and Helen Biggar were all influenced by Adler and Herman. Through his involvement with the New Art Club and New Scottish Group, Adler had a big effect on Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde. More widely, Joan Eardley, Ian Hamilton Finlay, Margot Sandeman, Bet Low and Cordelia Oliver were all being influenced by the exhibitions of Jewish and German art organised by Schotz and Herman.

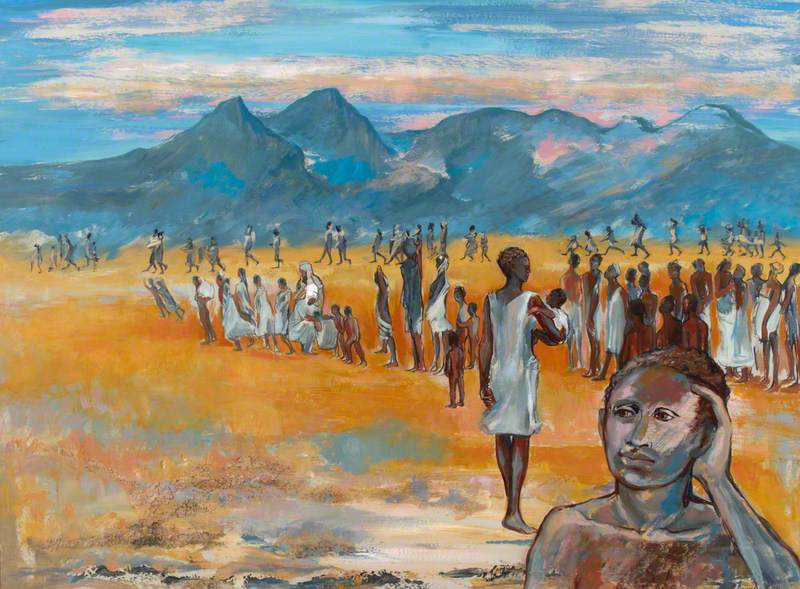

In 1951, the year of the Festival of Britain and Schotz's Festival of Jewish Art, another Jewish artist arrived in Scotland. This was Marianne Grant, a Czech artist born in Prague who survived the Theresienstadt Ghetto and Auschwitz concentration camp, before being liberated by the British army at Bergen-Belsen.

Grant painted and drew throughout the Holocaust. Her subjects – which ranged from 'ordinary' life in Theresienstadt to the huts of Auschwitz and the dead of Bergen-Belsen – were always expressed with compassion, no matter the circumstances. Her talent probably saved her life. An SS guard, for whose children she had made a fairy-tale book, brought her medicine when she was sick, and the infamous Nazi doctor Josef Mengele found her drawing skills useful.

Her arrival in Scotland in 1951 came as the Jewish influence on Scottish art was waning. Adler and Herman were long gone while Schotz retired from his position at the Glasgow School of Art a few years later. Jewish artists continued (and continue) to practice in Scotland, but no longer had the same concentrated influence of the 1940s.

Despite this, Grant illustrates how Scotland provided a home for so many Jewish artists fleeing persecution, and how they repaid their new home through their artistic influences. Her watercolours and drawings are now cared for by Glasgow Museums, and works by many of the artists I've mentioned can be found throughout Scottish collections, a fitting tribute to their influence on Scottish art.

If you'd like to find out more, you can discover more about Jewish artists in Scotland from the Scottish Jewish Archives Centre.

Ben Reiss, Collections Content and Liaison Officer at Art UK