The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an institution steeped in tradition, so it's not surprising it hasn't always had the most progressive attitude towards women. However, with the election of Rebecca Salter as the first female President of the Royal Academy at the end of 2019, it seems that this ancient institution is certainly moving in the right direction.

Although it took so long for female artists to be taken seriously as Academicians, women have been instrumental in the development of the Academy across the centuries. Here we take a walk through the history of the RA, focusing on the women who made it the institution it is today.

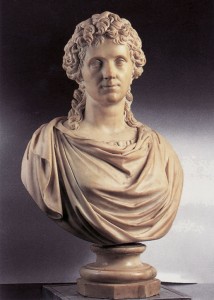

Angelica Kauffmann and Mary Moser, the founder members

It may come as a surprise that when the Royal Academy was founded in 1768, there were two women among the 34 original Members – fairly progressive by eighteenth-century standards. Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807) and Mary Moser (1744–1819) were both painters, Moser specialising in floral paintings and Kauffmann focusing on historical and allegorical subjects.

Euphrosyne Complaining to Venus of the Wound Caused by Cupid’s Dart

1793

Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807)

Both were from artistic families and received their artistic training from their fathers, as there were few European artistic academies that accepted female students.

By the time the Royal Academy was founded, Kauffmann and Moser were already established on the London – and European – art scene, which doubtless increased their prestige, making them irresistible candidates to become Members of the Academy. For women to succeed as artists, it was crucial to move in the right circles, and both Kauffmann and Moser had contacts aplenty.

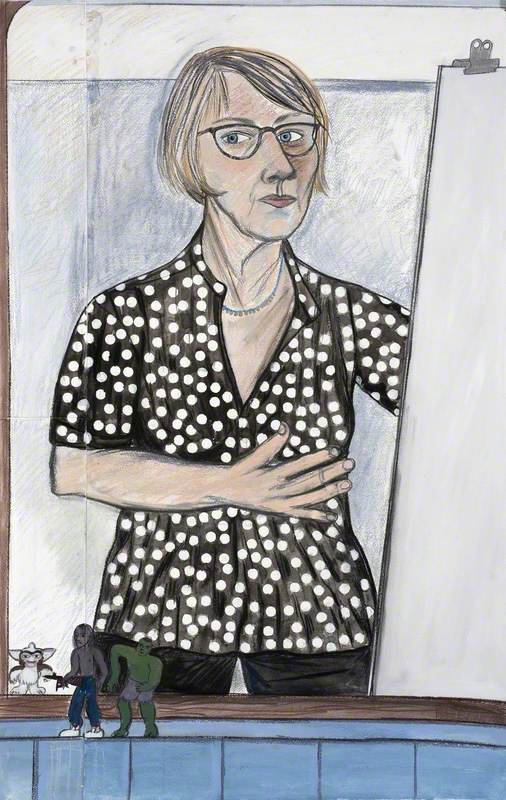

This is not to detract from these women's accomplishments as artists. In 1778 Kauffmann was commissioned by the Royal Academy to produce a set of four paintings showing the 'Elements of Art' for public display, and these works – Invention, Composition, Design and Colour – can still be seen in the RA's entrance hall.

Kauffmann had considerable influence in decisions made by the RA including vetoing Summer Exhibition paintings of which she did not approve.

Moser was a similarly respected artist, most notably receiving a royal commission in the 1790s to decorate part of Queen Charlotte's new residence at Frogmore, near Windsor. Moser was also active in RA affairs, particularly in her later years, as ill-health prevented her from painting. As a woman, she was barred from attending Academy dinners, but she regularly attended and voted at General Assembly meetings. Her two floral paintings that decorated the Academy's premises at Somerset House are today gems of the RA collection.

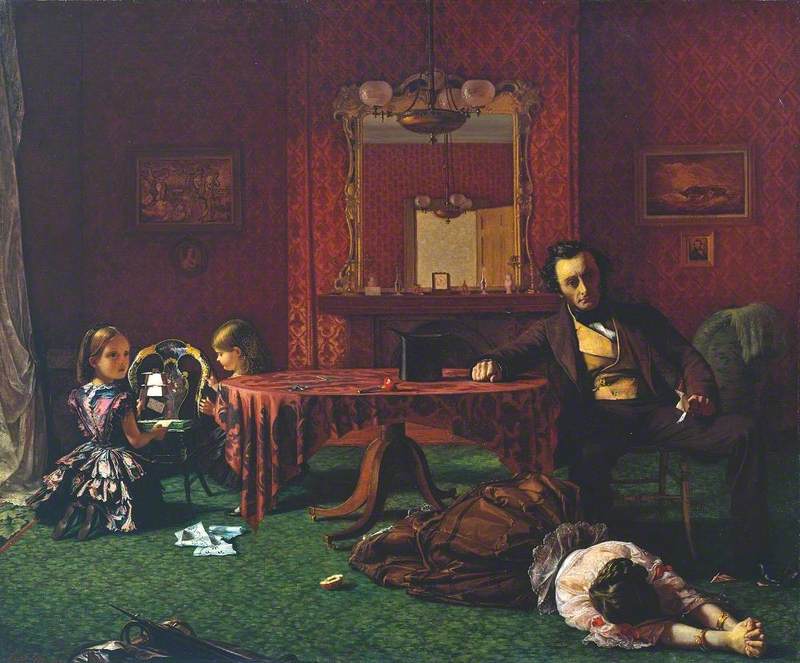

Despite both women's artistic eminence, they were excluded from many of the key aspects of the Academy simply due to their gender. They were not permitted into the Life Room to study and draw nude models, for example – key to practising the human form. And after Moser's death in 1819, it was over a century before a female Academician was elected.

Annie Swynnerton, the first female Associate

Although no female Academicians were elected in the nineteenth century, this does not mean that women were not active in the RA during this time. The annual Summer Exhibition always included works by female artists and in 1860 Laura Herford became the first woman to be accepted into the Royal Academy School, when she signed her application drawing with only her initials. The drawing was accepted before the professors realised Herford was a woman – but she was admitted nonetheless, her artistic merit shaking up the status quo.

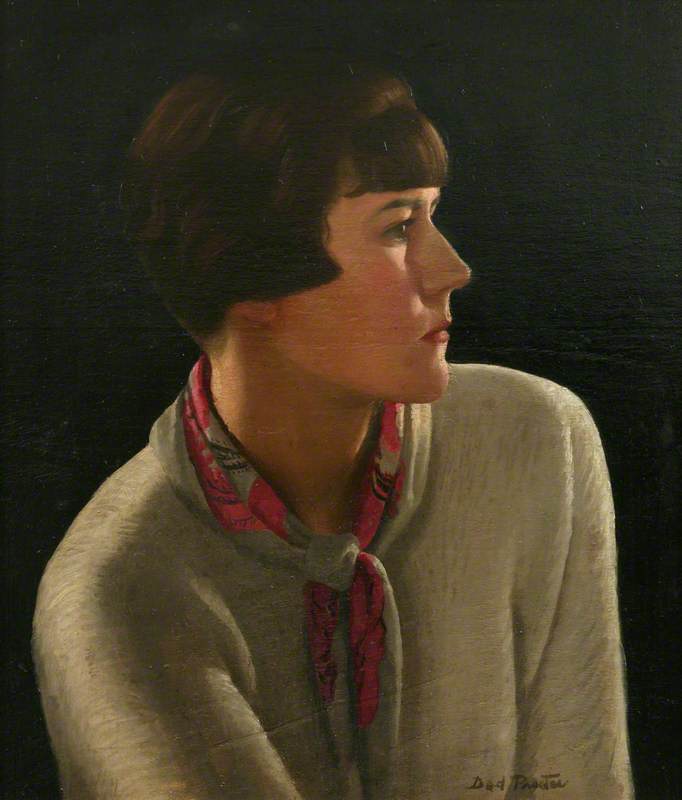

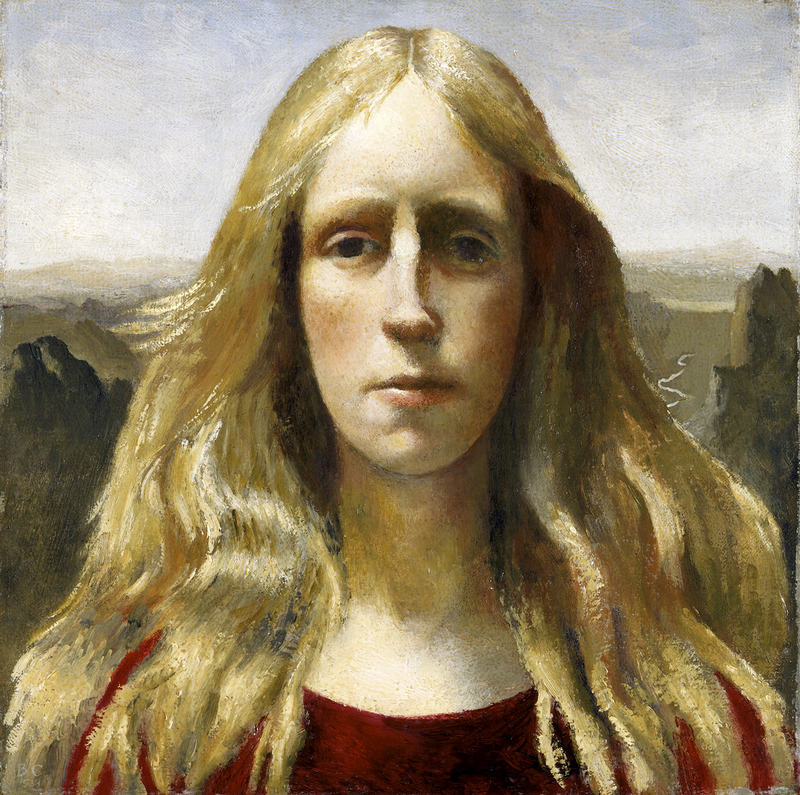

It was not until 1922 that Annie Swynnerton (1844–1933) became the first woman to be elected to the RA (Moser and Kauffmann were technically invited to become Members, rather than elected in the normal way). Swynnerton was a symbolist and portrait painter. She was an active supporter of women's suffrage, counting the Pankhursts among her close friends.

Her election to the RA impacted little upon the role of women more generally in the Academy, however; she was only made an Associate (not a full Academician) and was almost in her 80s, making active participation in the governance of the RA unrealistic.

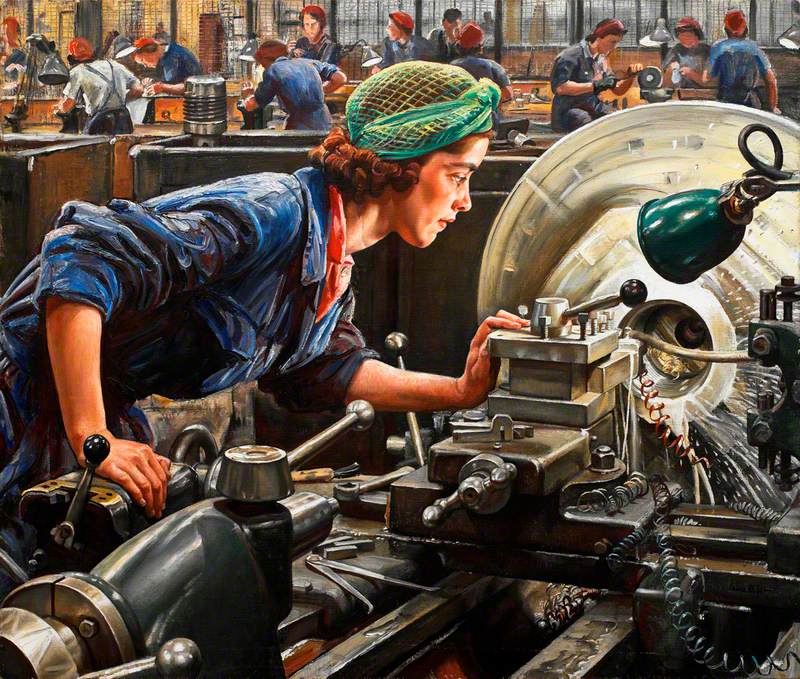

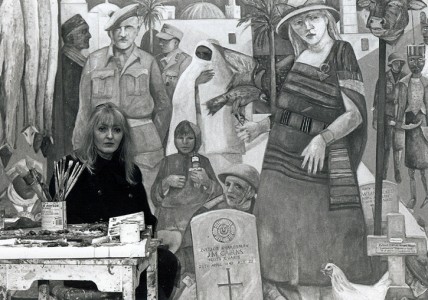

Laura Knight, the first full Academician

Swynnerton's election was the first pinhole in the floodgates for female Academicians. Just a decade later, the painter Laura Knight (1877–1970) was the first woman to be elected a full Academician. She paid tribute to her predecessor, describing how skilled women artists had been denied any public prominence until 'Mrs Swynnerton came and broke down the barriers of prejudice'.

Knight paved the way for further female Academicians and was a prominent public figure in the Academy's affairs. She was determined to establish her position on an equal footing with the men in the Academy, and befriended key figures within the RA.

In 1965, she was the first female artist to have a solo retrospective at the RA. But despite her popularity among the male Academicians, Knight had to wait until 1967 – having already been an Academician for 30 years – until she was allowed to attend a dinner at the RA, finally smashing through the boys' club mentality and dismantling the nearly 200-year-old tradition of male-only dining.

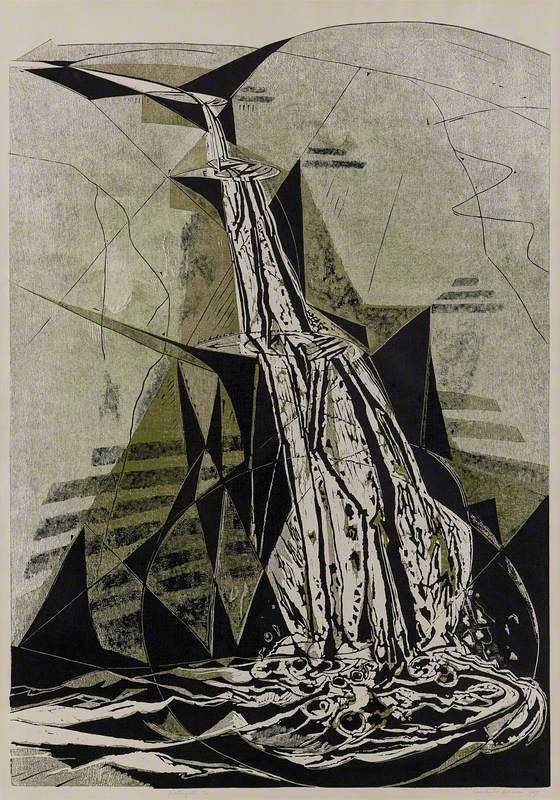

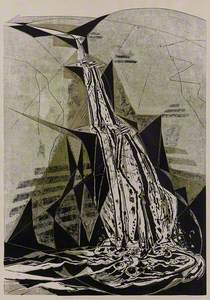

Gertrude Hermes, breaking down barriers

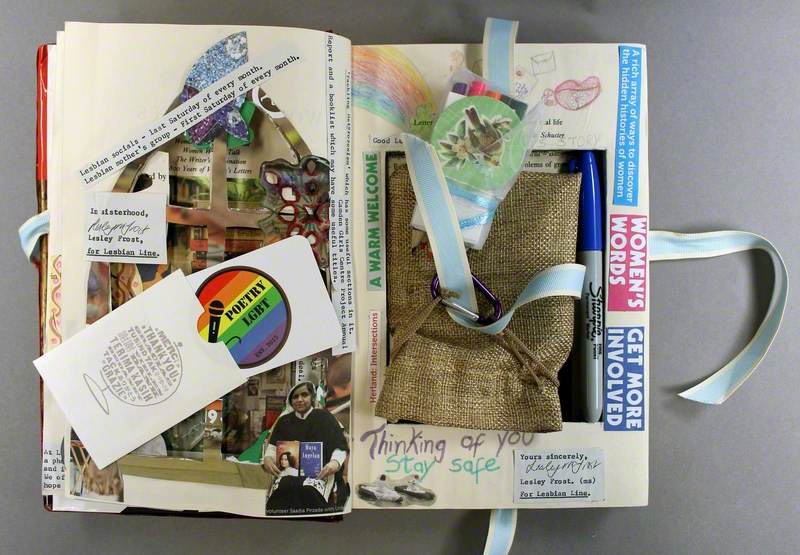

Knight had Gertrude Hermes (1901–1983) to thank for the dinner invitation. Hermes became an Associate Academician in 1963 and became the first female engraver to become a full Academician in 1971.

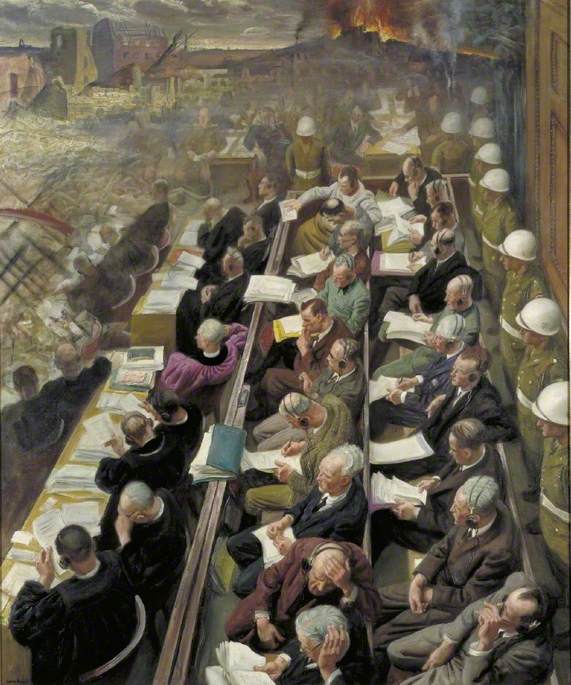

After a General Assembly meeting in 1966, Hermes was appalled to discover that while the male Academicians proceeded to the decadent dinner that they could smell wafting into the meeting room, women members were excluded.

She campaigned to overturn this archaic misogynistic dining mentality, and the following year four female Academicians – Hermes and Knight included – joined the men at a historic dinner. The Times newspaper reported that Hermes even enjoyed 'a thoroughly masculine cigar.' Touché.

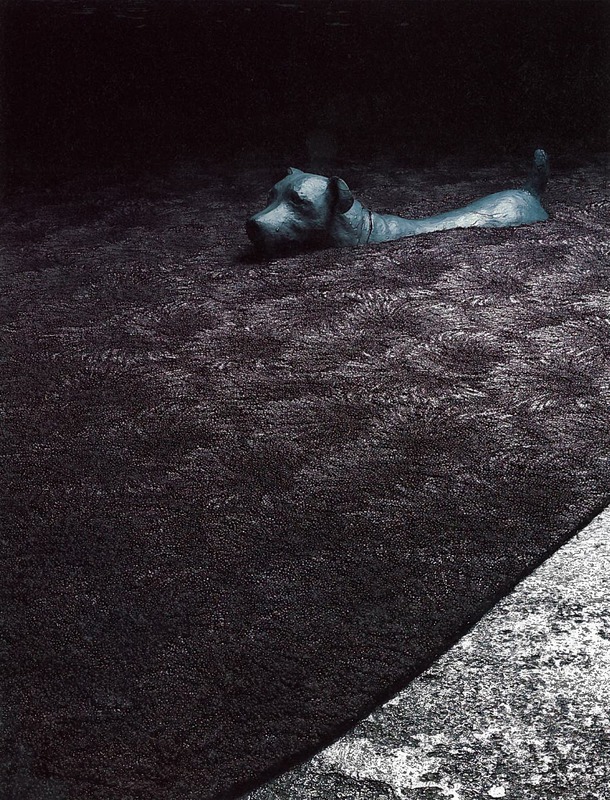

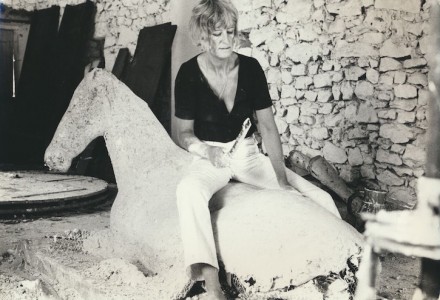

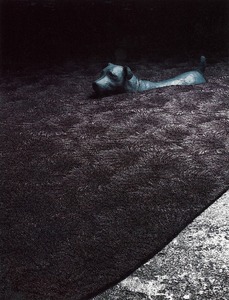

Elisabeth Frink, the first female sculptor

In 1977, Elisabeth Frink (1930–1993) was the first female sculptor to become an Academician, over 40 years after Laura Knight became the first painter Academician.

Sculpture was perceived as a traditionally masculine art, due to its physically demanding nature. But Frink demolished this misconception, becoming one of the most prominent British sculptors of the twentieth century.

As a teacher, she was also admired by a generation of student artists and was active on many arts advisory committees. Such was her status in the British art scene that she was proposed as the first female President of the Academy, but she declined to stand.

Female Academicians in the RA Schools

Notable firsts continued into the twenty-first century.

The year 2011 saw the election of Eileen Cooper (b.1953) as the first female Keeper of the Royal Academy Schools, having primary responsibility for the Schools and students.

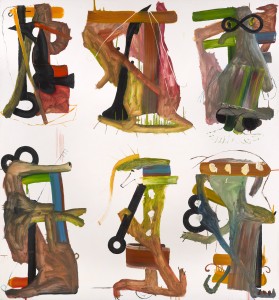

The same year also saw the first female Professors, Fiona Rae (b.1963) (Painting) and Tracey Emin (b.1963) (Drawing).

These historic appointments elevated the prominence of female art teachers, an influence which can now percolate through the next generation of artists in the RA Schools.

Under Cooper's tenure as Keeper, Cathie Pilkington (b.1968) in 2015 and Farshid Moussavi (b.1965) in 2017 became the first female Professors of Sculpture and of Architecture respectively.

Cooper set a precedent for female Keepers, with Rebecca Salter succeeding her in 2017 and Cathie Pilkington elected to the position in May 2020.

Rebecca Salter, the first female President

December 2019 was a historic moment for the Royal Academy: 251 years after its foundation, the Royal Academy finally elected its first female President – the printmaker Rebecca Salter (b.1955).

During her two years as Keeper, Salter had been intimately involved in the work of the Academy and its students. Her election as President was celebrated in all corners of the RA and beyond, as a momentous waymarker in the journey to gender equality within the Academy – and perhaps in the art world more widely.

Yet Salter has faced the most challenging first months of any President in the history of the Academy. The impact of Covid-19 and subsequent temporary closure of museums and galleries is proving catastrophic for the arts sector. All of the RA's exhibitions planned for 2020 and beyond have been rescheduled or cancelled altogether. This is a particular setback for female representation, as Marina Abramović (b.1946) was to have become the first female to have a dedicated solo show in the RA Main Galleries later in 2020, now pushed back to autumn 2021. Her time will come.

In a time of confusion and angst, one thing is for certain: when the RA reopens, it will resume its campaign for equality and representation, more determined than ever to bring art and opportunities to all. With Salter at the helm, steering the Academy through tempestuous seas, we can only look forward to the time when we can once again set foot in its historic galleries.

Over the past decade, an almost equal number of female and male Academicians have been elected, pushing ever closer to gender parity between Academicians. But the fight for equality and diversity does not stop there. It took over 250 years for women to reach any form of equal representation within the Academy. The fight for greater diversity cannot afford to wait any longer.

Helen Record, Curatorial Assistant at the Royal Academy of Arts