How can museum objects, such as nineteenth-century paintings, help us understand the history of the environmental crisis? And how might this understanding help us shape our response to that crisis?

In early 2022 I went to Glasgow to make a short film for the Open University called 'Landscapes of Change'.

Drawing on the city's extensive collections, housed in several museums, I wanted to tell a story about pollution, with reference to two rivers: the Clyde in Glasgow, and the Seine in Paris. Both rivers were hugely affected by industrialisation and its side effects in the nineteenth century, a process that created both visible changes (riverside factories, steam-powered transport) and less visible changes (loss of biodiversity in and around the rivers).

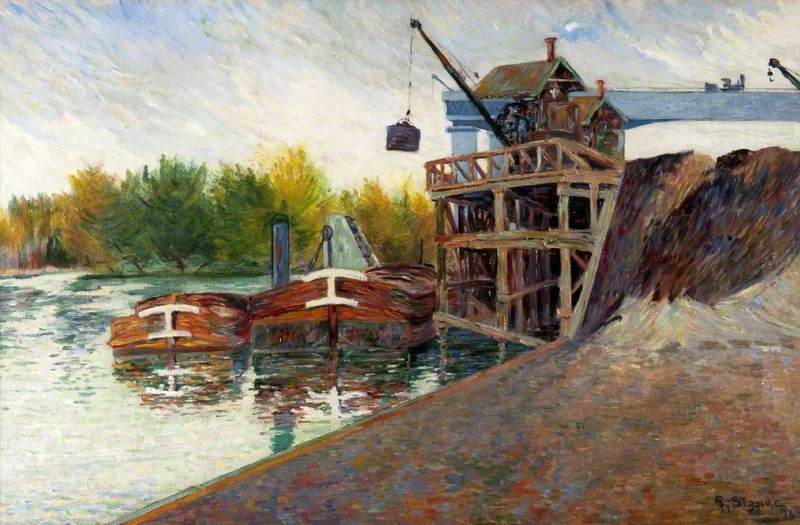

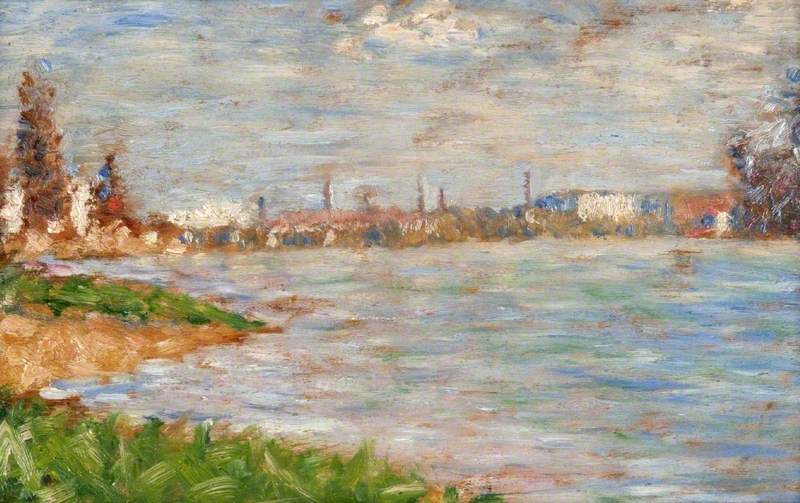

My interest in the Seine led me to the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum and its excellent collection of Impressionist paintings. These include several images that deal explicitly with industry and the Seine, such as Paul Signac's Coal Crane, Clichy (1884) and Georges Seurat's The Riverbanks (c.1882–1883).

The second of these is one of several studies for Seurat's large-scale Bathers at Asnières (1884), the famous painting owned by The National Gallery, which depicts a group of bathers taking a swim – or about to take a swim – just across the water from a prominent gas plant.

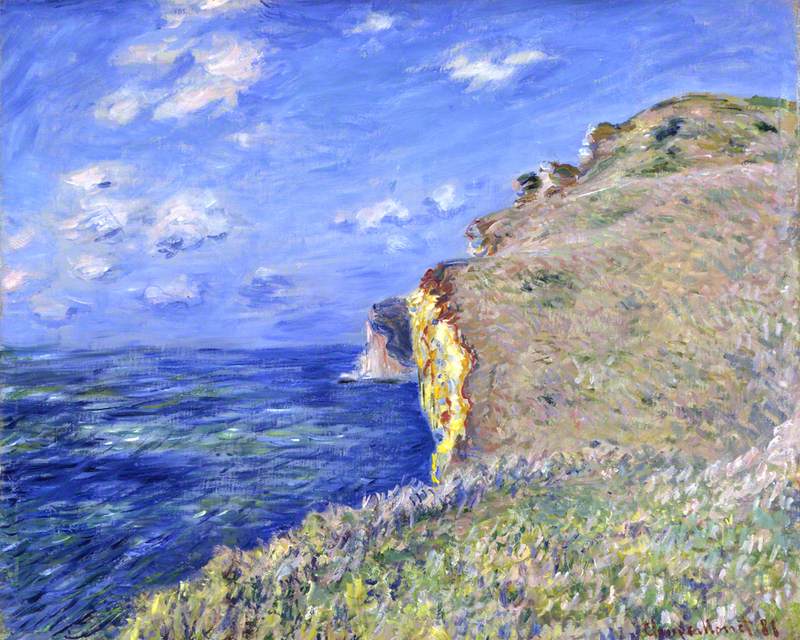

These paintings remind us that many of the artists associated with Impressionism engaged with the subject of industrial expansion – that is to say, they didn't ignore changes in the landscape, but actively sought out landscapes that were changing. Monet, Manet, Signac and Seurat all frequented areas (Parisian suburbs such as Clichy, Asnières, Argenteuil, and Pontoise) where leisure and industry collided.

The painting that intrigued me most at the Kelvingrove, however, was of a slightly different kind. Camille Pissarro's The Banks of the Marne (1864) represents a woman walking along a quiet path on the side of a river.

The Marne is an eastern tributary of the Seine, and this painting was probably created not far from Paris. However, it is clear that we are not dealing with the industrial suburbs here, but a much more distinctly rural scene.

Or is it? Pissarro would go on to create many paintings representing industry, both in Paris and further afield. But is this canvas one of them? It all comes down to a few flicks of the paintbrush on the right of the canvas. That line of dark paint emerging from behind a bank of greenery above the river – is it a chimney (indicating the presence of a factory), or is it a lone, tall tree? Or could it even have been painted in such a way as to suggest both?

I think the question is an important one – and a difficult one to answer. I've spoken to people who are convinced that it is a tree (a poplar, surely?) and others who maintain that it is a chimney (isn't that a little plume of smoking coming out of it?) One clue, perhaps, lies in the existence of a study in The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

Here it is very clearly a poplar tree. So why the change? Why did Pissarro shorten and straighten his tree between his study and the finished work?

Looking at other paintings by Pissarro may help us here. Pissarro is well represented in UK collections, and of the 60 paintings on Art UK, at least ten of them contain some signs of industry. Most of these are dated later than The Banks of the Marne, and are much less oblique in their references to industrialisation. Nonetheless, the visual playfulness that I believe accounts for the tree-chimney in The Banks of the Marne, is still very much evident.

The Quai du Pothuis at Pontoise after Rain (1876), at the Whitworth in Manchester, is a case in point.

The Quai du Pothuis at Pontoise after Rain

1876

Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)

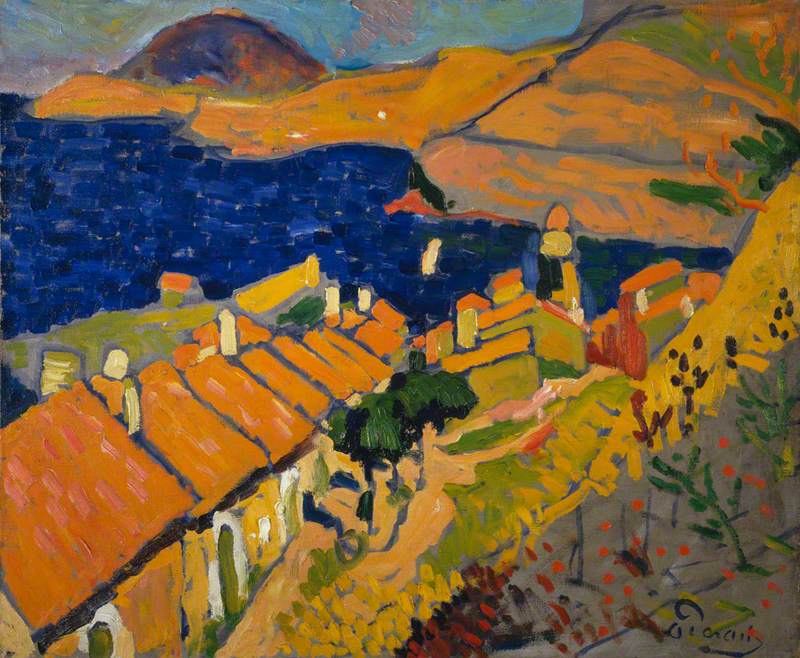

Pontoise is a northern suburb of Paris, where Pissarro lived in the 1870s. Like many suburbs, it was a shape-shifting sort of place, your sense of which would differ depending on which direction you were facing. Pissarro painted both its more traditional, rural aspects, as well as the areas that were undergoing radical changes.

He never ignored the factories built on the banks of the River Oise – as other landscape painters may have done – but sought out inventive ways to bring them into the frame. In The Quai du Pothuis at Pontoise after Rain, the smoking chimney appears behind the trees at centre-right. It's puffing out grey smoke, and can't be mistaken for a tree this time, although Pissarro does place a tree of the same height next to it. This creates a visual echo, which is repeated in the lamppost to the left of the chimney.

Lamppost, chimney, tree: these three vertical objects, different in function but similar in form, are brought together on the canvas. They stand together in a triangular formation, almost like three figures standing for a portrait. This triangular formation is echoed in the shape of the clouds above, which rise to a gentle peak above the chimney.

What is going on here? Pissarro is playing with the forms he finds in the landscape. Factory chimneys, for all that they may represent an eyesore, if not an environmental hazard, can nonetheless be safely carried into a landscape painting, if kept at a distance, and brought into play with other forms. The verticality of the chimney balances the verticality of other objects. Paint it hazily enough and you might even mistake it for a tree or a church spire.

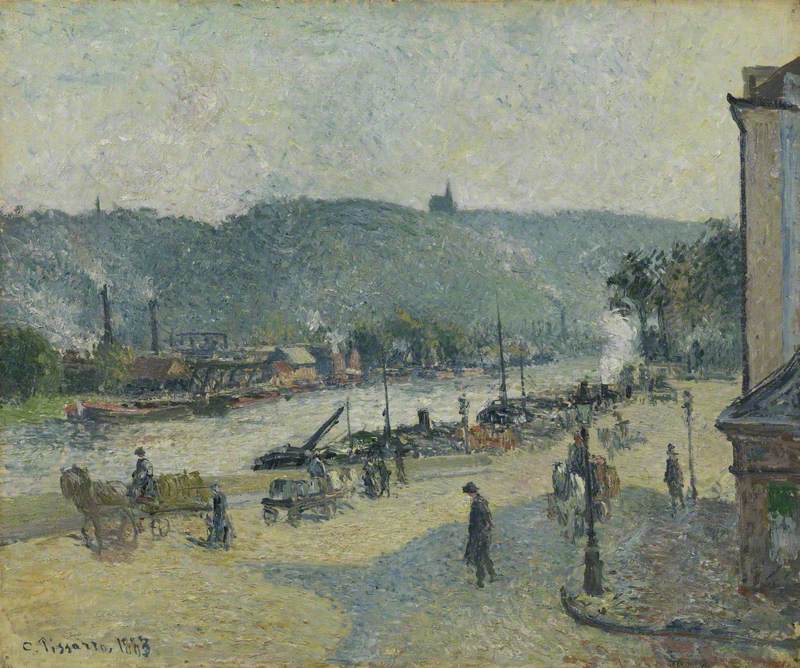

In another painting from the 1880s, this time depicting the port city of Rouen, Pissarro lines up a collection of vertical objects, including factory chimneys, a spire, lampposts, boat masts, and trees. The factory becomes a kind of secular church.

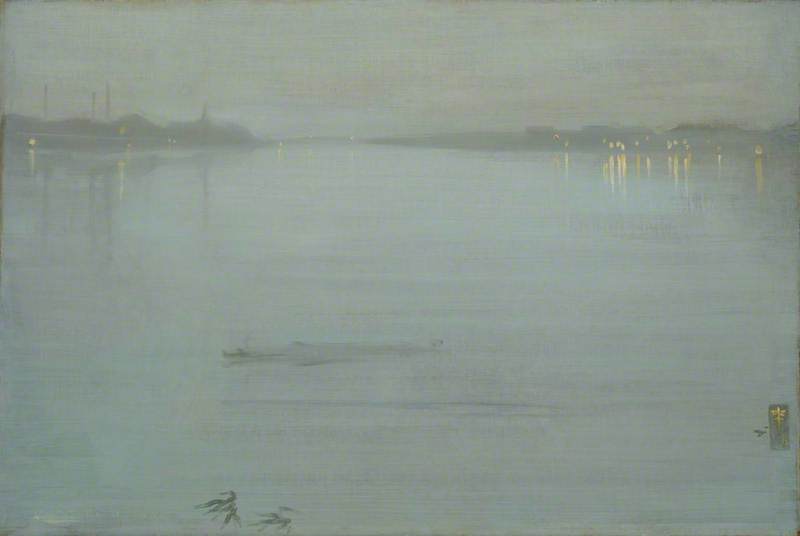

None of this is particular to Pissarro. James McNeill Whistler had been doing a similar thing in London in the 1870s, painting the industrial landscapes of Battersea in London in such a way as to suggest the hidden beauty of modern factories, if viewed in the half-light of night, from the other side of the river.

Claude Monet, meanwhile, took a particular fancy for the atmospheric effects of steam trains.

Pissarro, however, seems to have returned to the subject more than most, and it is likely – given Pissarro's anarchist political beliefs – that he was at least partly driven to paint industry through his sympathy with the working classes. That said, sympathy did not mean that Pissarro had ever experienced factory conditions, and in his many paintings of industrial landscapes he remains very much an observer. He is able to play with the forms of factory chimneys, and compare them with towering poplars, because the factory for him is an object, not a social reality.

Could we say the same thing about ourselves? Many of us will have grown up in or around landscapes dotted with gas plants and cooling towers. There is less visible pollution now than there was in the late nineteenth century, but smoking chimneys are still a part of our landscapes. How do we see these objects? Do we shut them out (turn the other way entirely) or do we take a Pissarro-like approach, and try to bring them into the frame by comparing them to trees or church spires? And is this latter approach just a different kind of blindness: a way of seeing something without really comprehending it? If you'd rather it wasn't a chimney, imagine that it is a tree, and that the smoke coming out of it is not pollution, but a small grey cloud.

As I sought to show in my film, paintings such as The Banks of the Marne can help us understand the way that artists visualised pollution, and can encourage us to reflect on the way we visualise those same themes today. Pissarro would have been aware that riverside factories caused pollution, but the long-term effects of that pollution on, say, the biodiversity of the river, were probably not on his mind. To critique Pissarro's paintings of pollution is not, then, to critique the artist's lack of awareness, but to question what these images can teach us about the way we make sense of our relationship with the wider environment.

Samuel Shaw, Open University