British sculpture owes a lot to sculptors who arrived here from abroad. Some were so important that they are routinely included in national histories.

Even though Henri Gaudier-Brzeska was from France, and Jacob Epstein from the USA, they are more part of a 'British' story than any other.

If for Epstein that makes sense, because he spent most of his long life here, in the case of Gaudier it perhaps has more to do with Britain's need to find some examples of modern sculptors for its early twentieth-century canon. And indeed, although Gaudier was espoused by the critic and curator H. S. Ede, whose collection resides at Kettle's Yard in Cambridge, and where you can see good examples of Gaudier-Brzeska's small but radical work, there is a more important holding of 122 works in the Pompidou Centre in Paris.

National histories are invariably treacherous. Epstein seems to have made the trip from Paris to London because he wanted to see the sculptures in the British Museum, which holds an important place in the story of modern sculpture (examples of those who were inspired by the collection range from Henry Moore to Ronald Moody, and from Rodin to Picasso). Epstein stayed, and became an established, if controversial, part of the British canon.

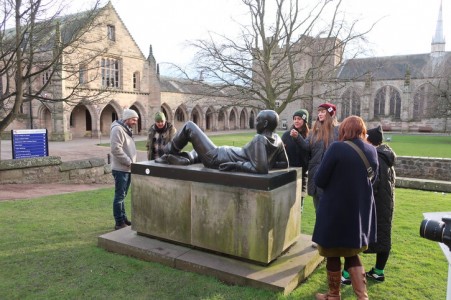

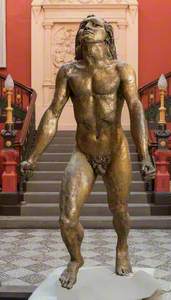

Saint Michael and the Devil

1955–1960

Jacob Epstein (1880–1959) and Morris Singer Art Foundry Ltd (founded 1927)

Gaudier and Epstein chose to come for personal reasons, but by the 1930s there were pressing political reasons for artists (as for anyone) to seek a new home here.

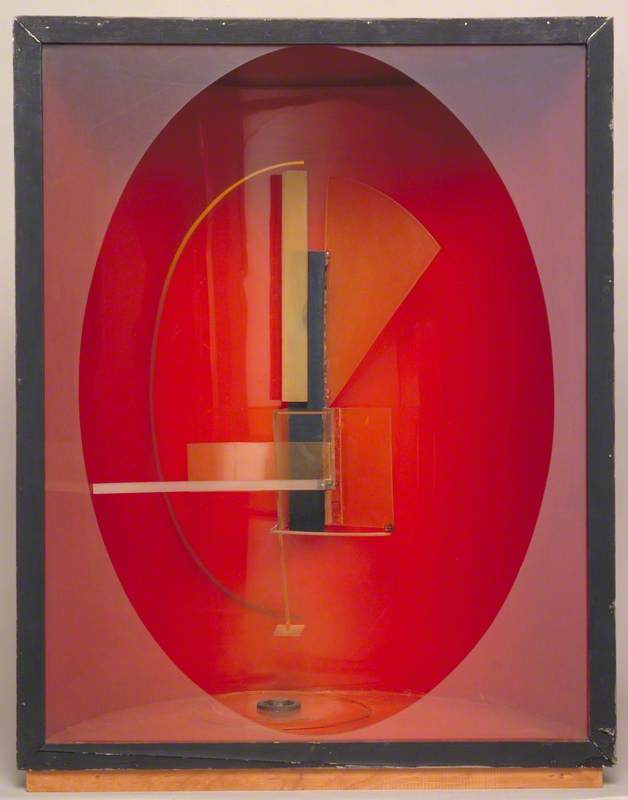

Naum Gabo, who left his enormous archive to the Tate, was an important migrant on route, ultimately, to America.

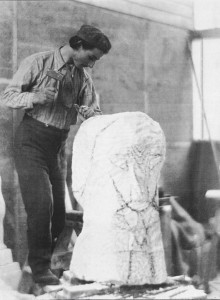

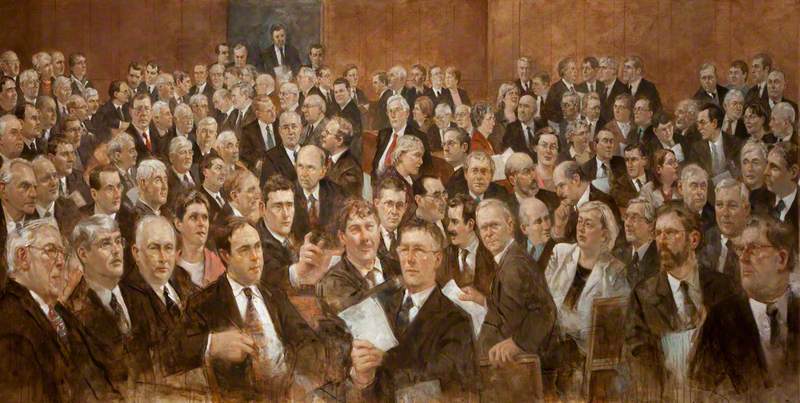

But there is a surprisingly large group of less well-known émigrés, who also arrived in London in the 1930s and stayed on. Many of them feared for their personal safety, as well as their livelihoods, but they were by no means necessarily 'modern', and sometimes even more traditional than the British establishment. Indeed quite a number of these refugees found a kind of home-from-home in the form of the Royal Academy, and also within the conservative climate of official portraiture and medal-making.

Artists from Germany and Austria, as well as from Central Europe, fleeing Nazism and the rise of the totalitarian state, were surprisingly often better trained and suited to taking up the task of making portraits of the royal family and other dignitaries.

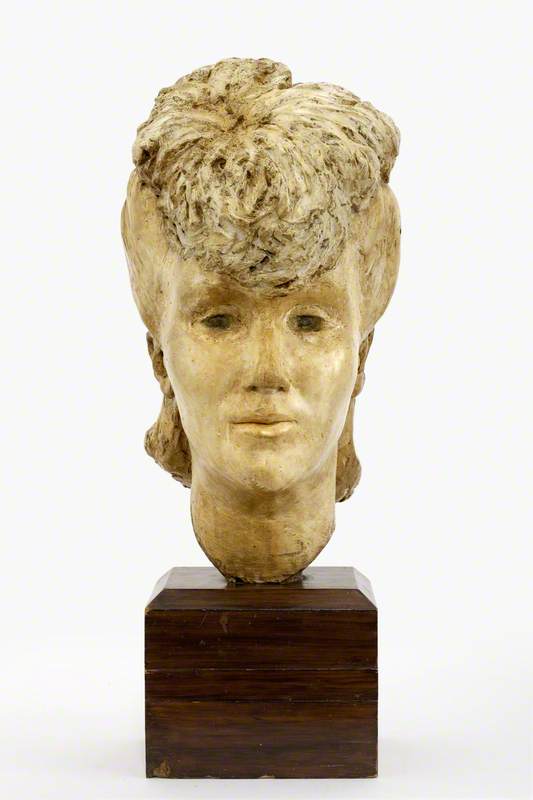

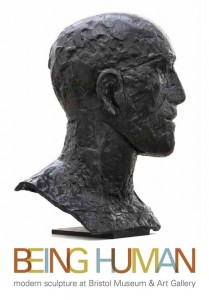

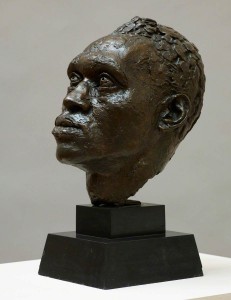

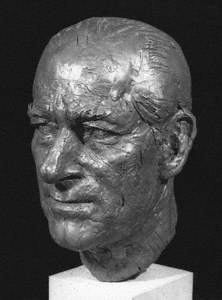

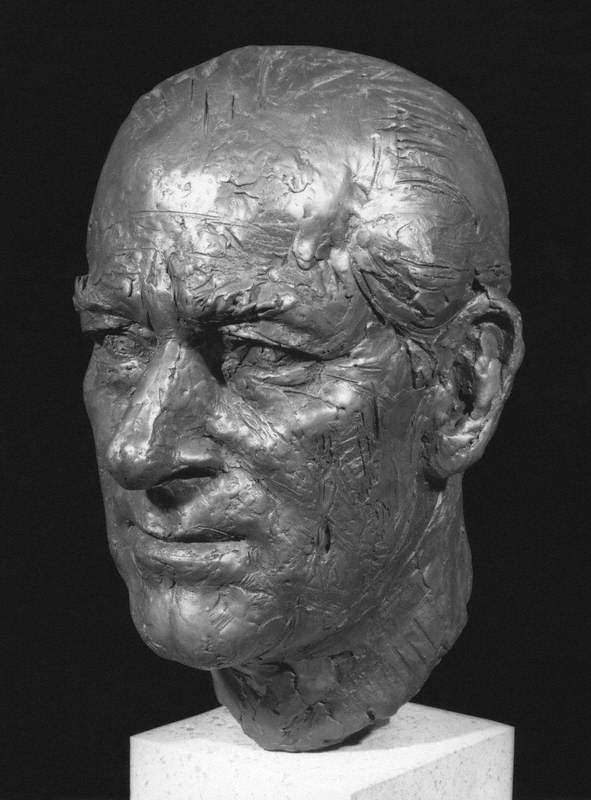

Prince Philip (1921–2021), Duke of Edinburgh

1979

Franta Belsky (1921–2000)

Such portraits – notably by Franta Belsky, also by Oscar Nemon – can be found in the National Portrait Gallery (where there are also informative photographs of the sculptors at work) and across Britain, in museum collections and in official spaces.

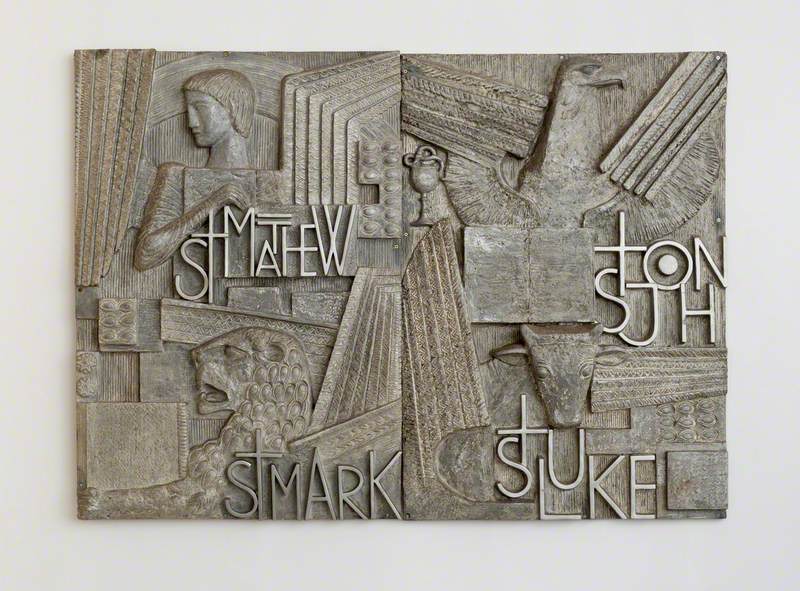

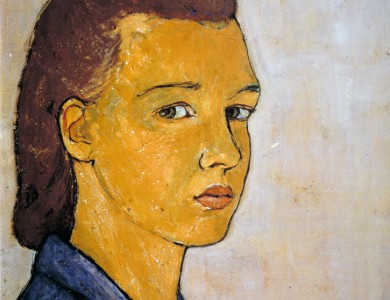

Helen Violet Bonham Carter (1887–1969), née Asquith, Baroness Asquith of Yarnbury

1960

Oscar Nemon (1906–1985)

A wide range of European sculptors arrived in Britain in the 1930s. Many of them, but not all, were Jewish, and many of them, but not all, were to become Royal Academicians.

They included Uli Nimptsch from Germany.

Siegfried Charoux, Georg Ehrlich, Anna Mahler and Willi Soukop came from Vienna.

Franta Belsky made the journey from Czechoslovakia.

Oscar Nemon came from what is now Croatia.

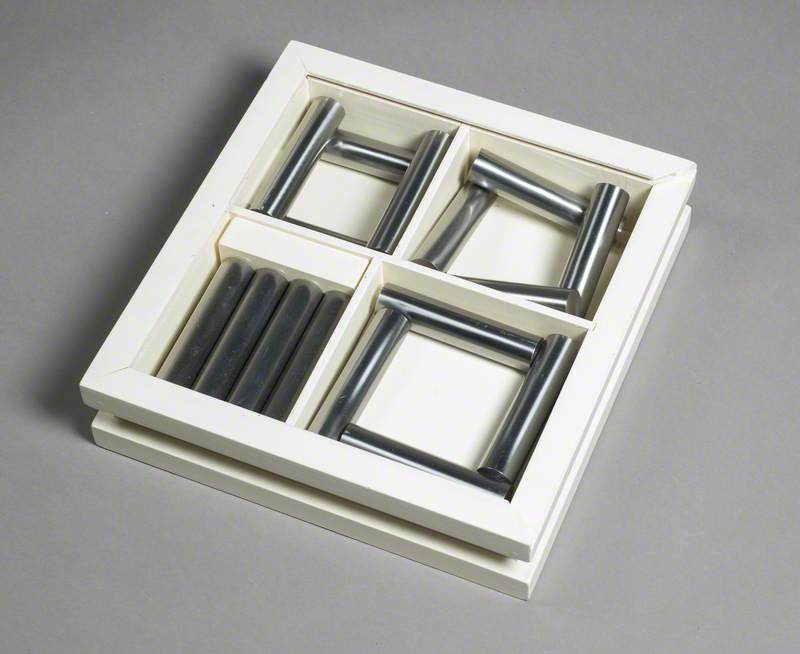

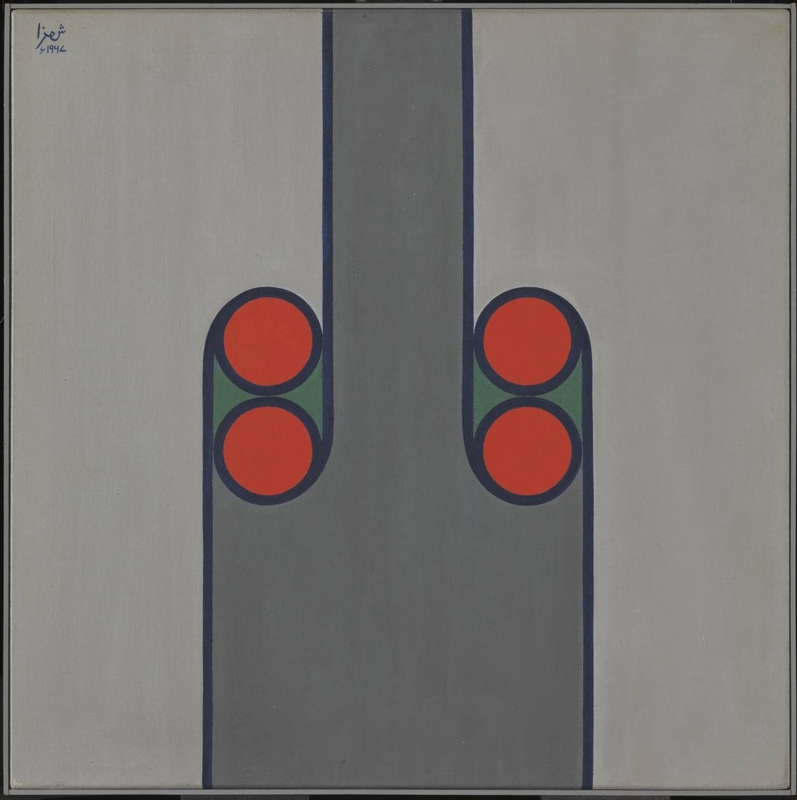

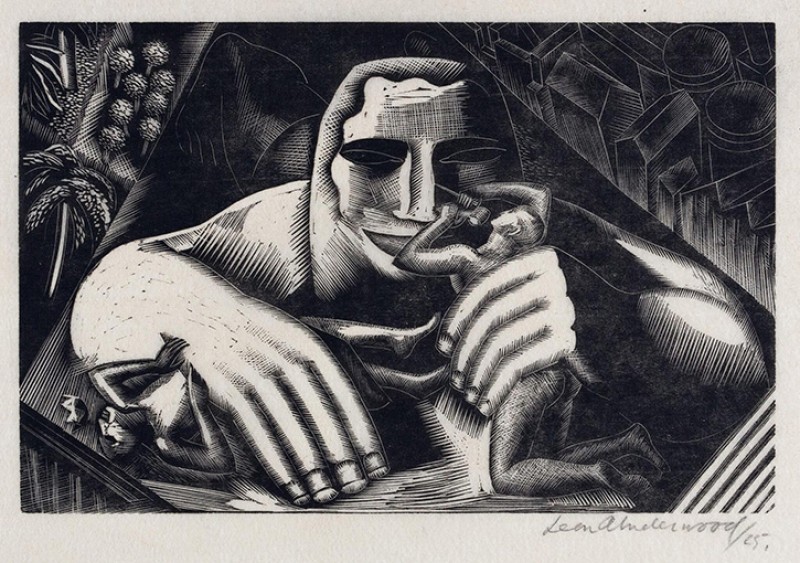

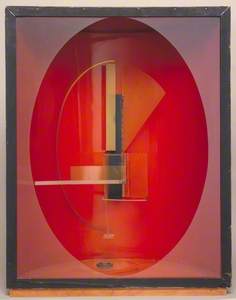

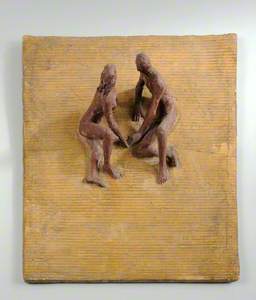

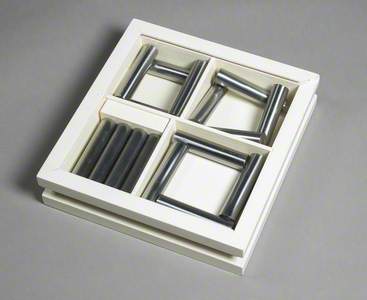

Representing Sporting Figures in Cubo-Futurist Style

Oscar Nemon (1906–1985)

And Peter Laszlo Peri came to Britain from Hungary.

Each of these artists has a story specific to him or her alongside a common (forced) trajectory towards this country.

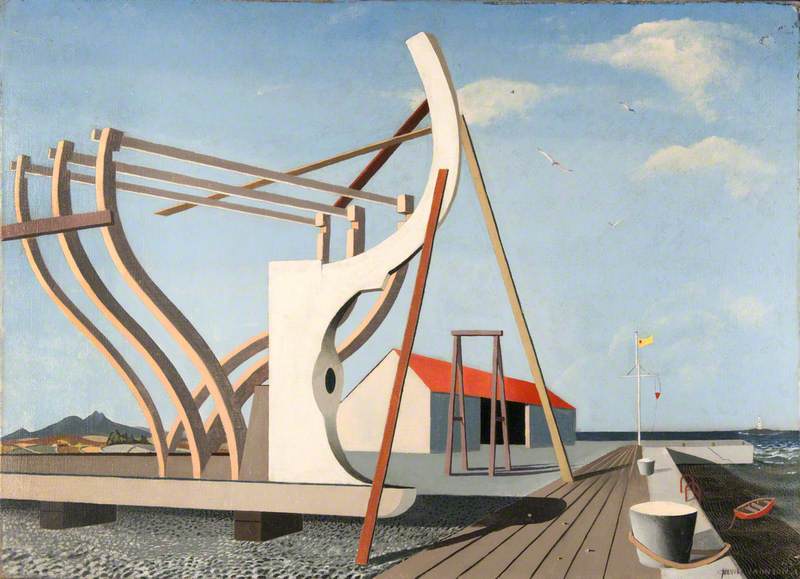

As Britain emerged from the war and began to plan for the Festival of Britain (1951) there seems to have been an implicit desire on the part of the organisers to include a diverse range of practitioners, and many non-British sculptors were invited to contribute, especially to the public sculpture on the South Bank.

Artists such as Charoux and Peri had more experience in making 'public art', which was a newer concept in Britain than on the Continent, but one that grew importantly after the war. This non-British aspect of a festival designed to celebrate Britishness often goes unremarked. Peri in particular went on to make sculpture for a large number of British schools, notably in Leicestershire.

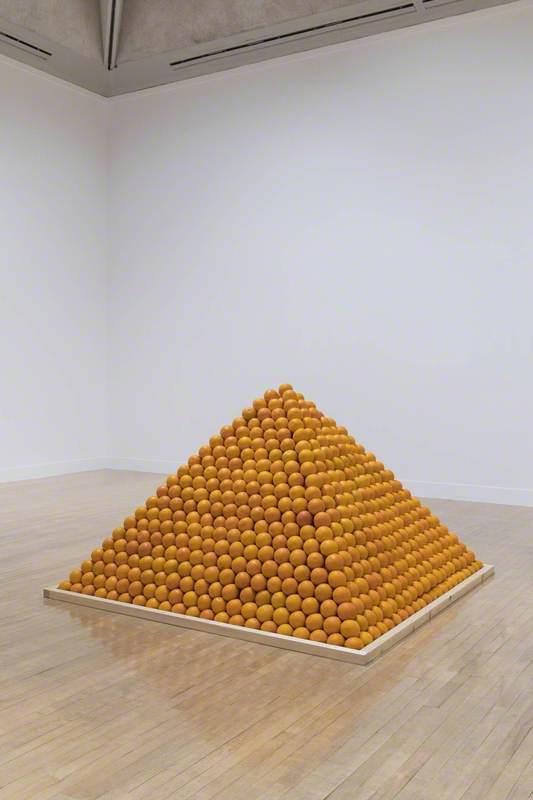

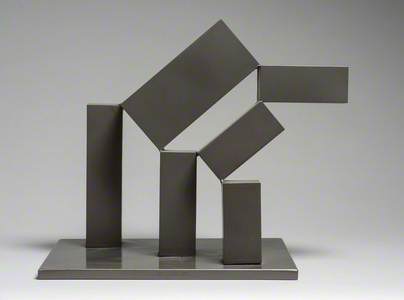

Another moment which one might single out in terms of the geographical diversification of British sculpture relates to students from the then Commonwealth coming to London to study. This was almost traditional, at least until the 1960s, but there is a moment around 1965 when the so-called new British sculpture is notably not British. Those attracted by Anthony Caro's presence and by the teaching at St Martin's include a number of Commonwealth students, including Roelof Louw from South Africa.

And of the six artists described as British in the 1965 'New Generation Sculpture' show at the Whitechapel Gallery, and again in 1966 in the famous 'Primary Structures' exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York, two – Isaac Witkin and Michael Bolus – were from South Africa.

Whether or not an artist becomes 'British' is not straightforward. It does not necessarily depend on where they made their home, or their work. There are complicating factors including the desire of a cultural establishment to embrace their values and what they mean, or the opposite.

While some British-born artists (William Tucker is a good example; Garth Evans is another) have spent most of their careers in the States, Tucker is still included in British histories but Evans is not.

Such outcomes are not accidental but depend on critical and commercial fortunes which can be complicated to unravel.

Penelope Curtis, art historian and fellow at the National Gallery of Art in Washington