Download and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or TuneIn

Art Matters is the podcast that brings together popular culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

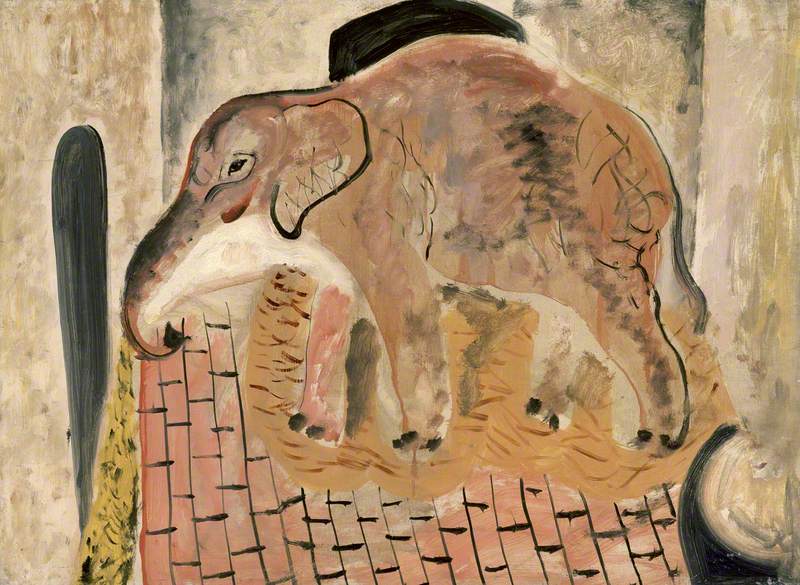

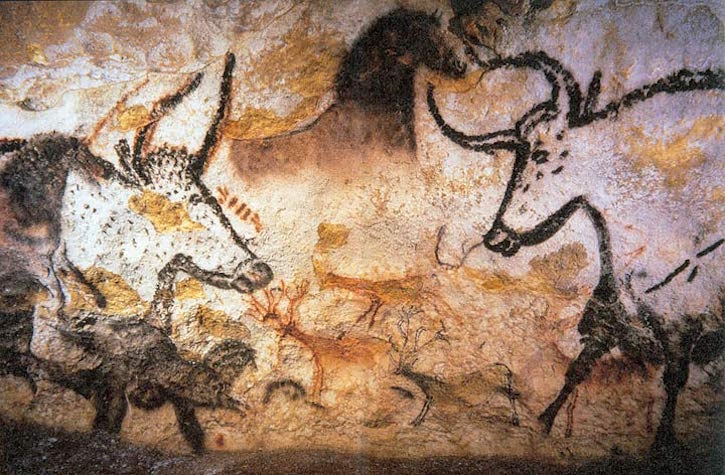

Think about some of your favourite childhood tales like The Three Little Pigs or The Tortoise and the Hare. Many of the stories we tell around the world involve animals, giving them human traits to convey ideas and moralistic lessons. These trends can be seen in art as well, and paintings of animals can be traced back thousands of years. Some of the oldest examples are in the caves at Lascaux, which are around 17,000 years old and portray stags, cattle, horses and many other species.

Paintings in the Lascaux caves (Montignac, Dordogne, France)

'My generation grew up with the idea that what was painted on cave walls was pretty much a shopping list,' says Giovanni Aloi, educator, curator and Editor-in-Chief of Antennae: The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture. 'Those theories have been discounted as simplistic and more recently, animals on cave walls have been associated to shamanistic rituals and storytelling.'

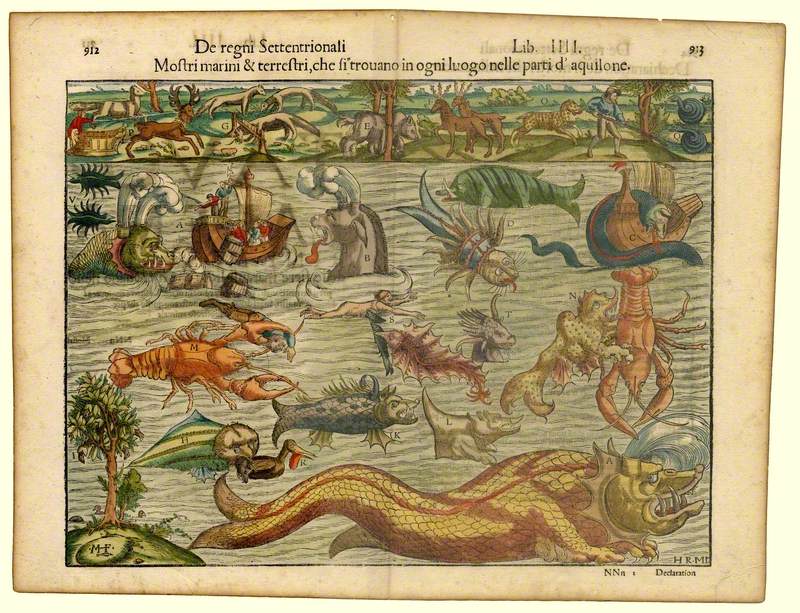

The use of animals in Western European art changes across time, where we can observe different social, religious and political associations with animals across different locations and periods. In the Middle Ages, beautifully illustrated texts known as bestiaries were some of the most popular books of the period. These were religious books using animals to convey moral lessons. The animals might be portrayed in colourful and whimsical ways, and they even included mythical creatures such as unicorns and dragons.

Exhibition of a Rhinoceros at Venice

probably 1751

Pietro Longhi (c.1701–1785)

As we move into the Renaissance period, we see a movement towards greater realism in the portrayal of animals. Albrecht Dürer created an etching of an Indian rhinoceros from a written description and, while it was not entirely accurate, it was fairly close and shaped European ideas of rhinoceroses for centuries – only supplanted by images of the celebrity rhino Clara in the eighteenth century.

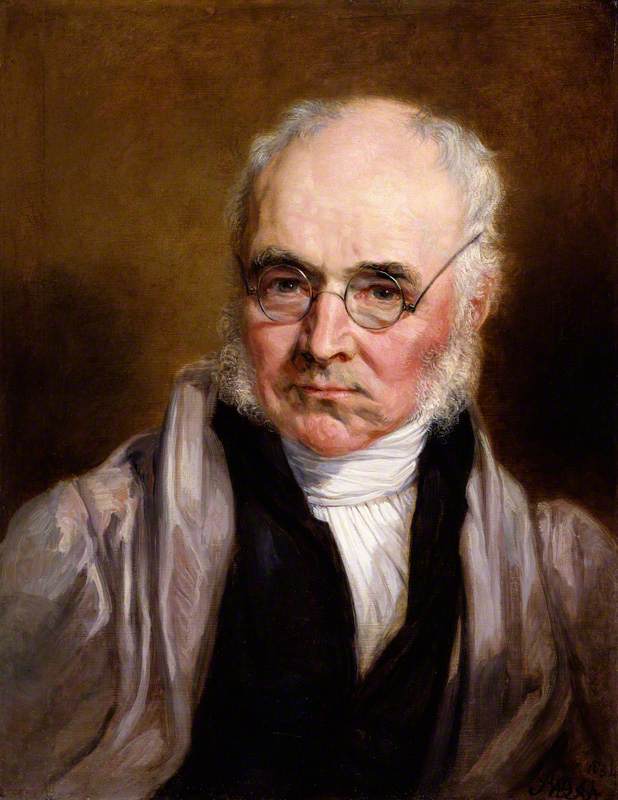

A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling (Anne Lovell?)

about 1526-8

Hans Holbein the younger (c.1497–1543)

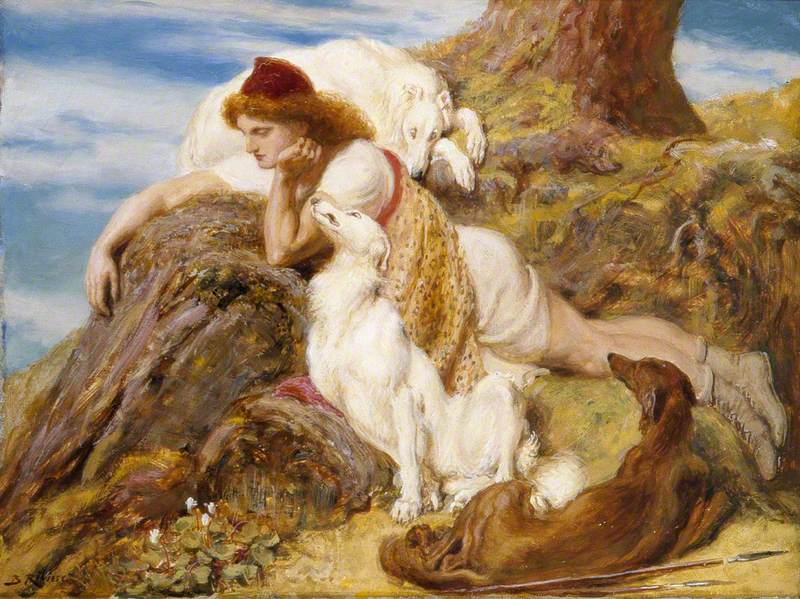

In England, another German painter, Hans Holbein the younger, offers an example of a cryptic use of animals in paintings with the portrait A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling. The squirrel on her shoulder is a reference to the Lovell family, who have a squirrel on their coat of arms. The starling is a play on words – the family had a large estate in East Harling which, when said aloud, sounds like 'a starling'.

'Animal symbolism is not something that's easy to unpack and universally read. It's not something that has an explanation across time, where you can say the squirrel symbolises this every single time,' says Giovanni.

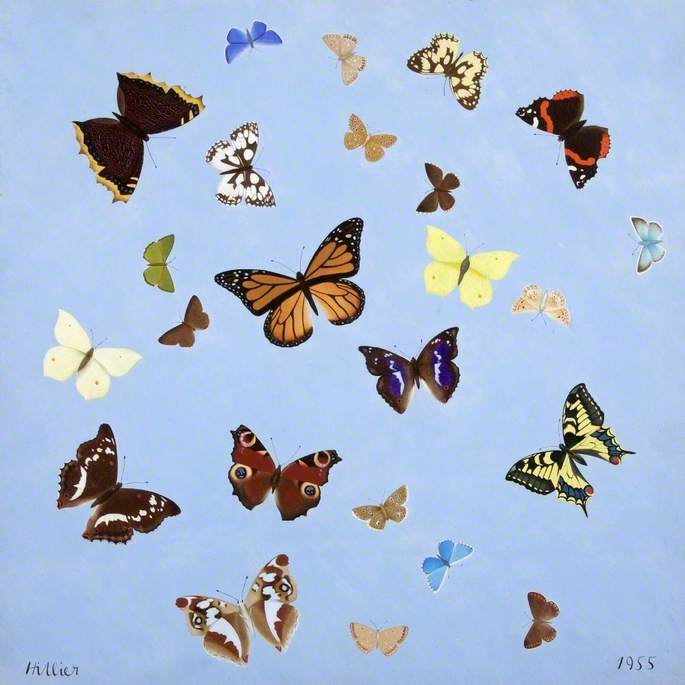

Realism in animal paintings flourishes in the works of Dutch Golden Age artists. Rachel Ruysch excelled at vibrant still life paintings of flowers, sometimes nestling butterflies, frogs, and insects amongst the petals and leaves. Hunting and market stall still lifes brought animals more to the fore, and these subjects became more popular and laced with symbolism during the Protestant Reformation. Flemish painter Frans Snyders was one of the earlier specialists in this genre.

'The animals that we see on a market stall don't just represent wealth and abundance and the power of the landowners who could provide game, but also have symbolic values that are associated directly with Christianity,' says Giovanni. 'Doves most often symbolise the holy spirit and boars symbolise gluttony. Peacocks symbolise resurrection... The swan symbolised betrayal – which might be a surprise to us since today we think of the swan as elegance and love – but the association with betrayal came from the colour of the feathers, which is pure white and the colour of the skin, which is black.'

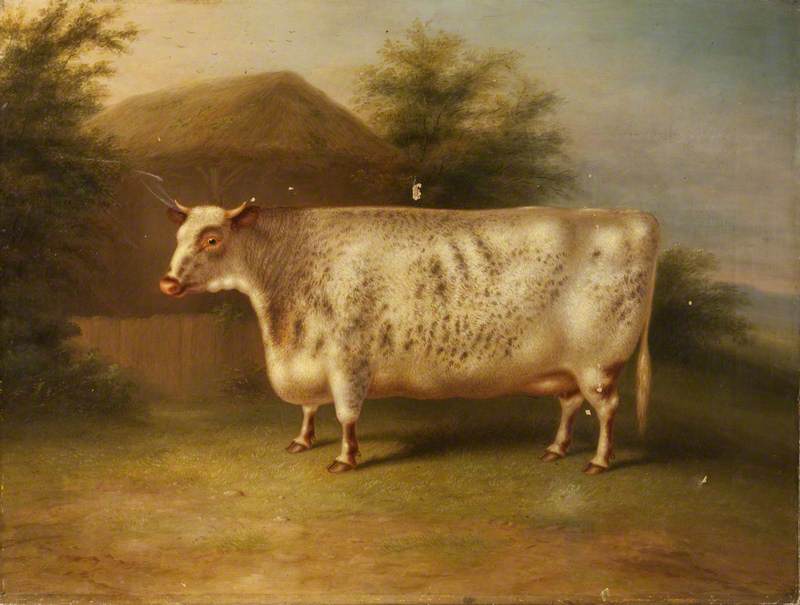

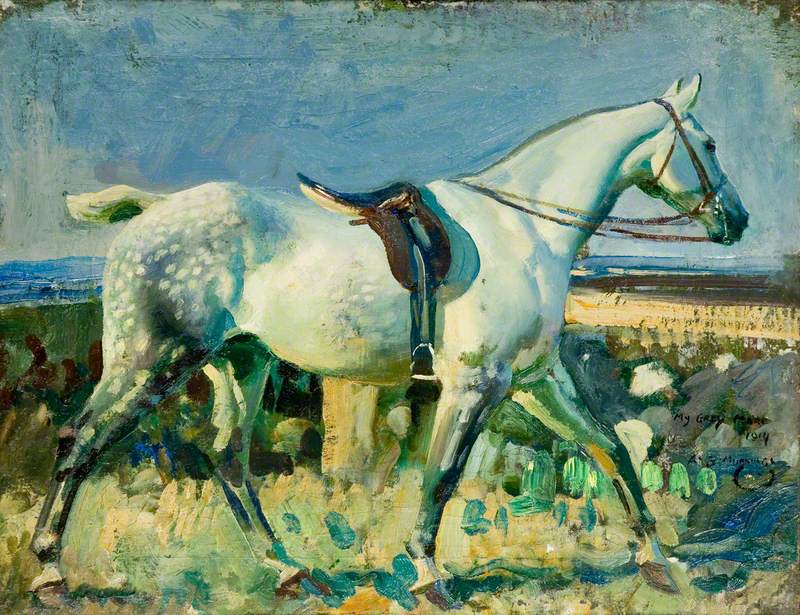

One of the most noted animal painters in the history of art is George Stubbs. His most famous painting Whistlejacket, found in The National Gallery in London, focuses on a particular racehorse and dedicates space to an animal in a way that had not been done in painting before. He was an Arabian thoroughbred racehorse that belonged to the Marquess of Rockingham and, while he won many races, was known to be difficult to manage.

'This is anatomically accurate, this is realism at its best and it doesn't have a rider. So that's really the groundbreaking moment with Whistlejacket. The tradition of art history from Jacque-Louis David to Velázquez and Ruebens and all the other great equestrian portraitists had trained us to see horses in the service of a king or a powerful royal,' says Giovanni.

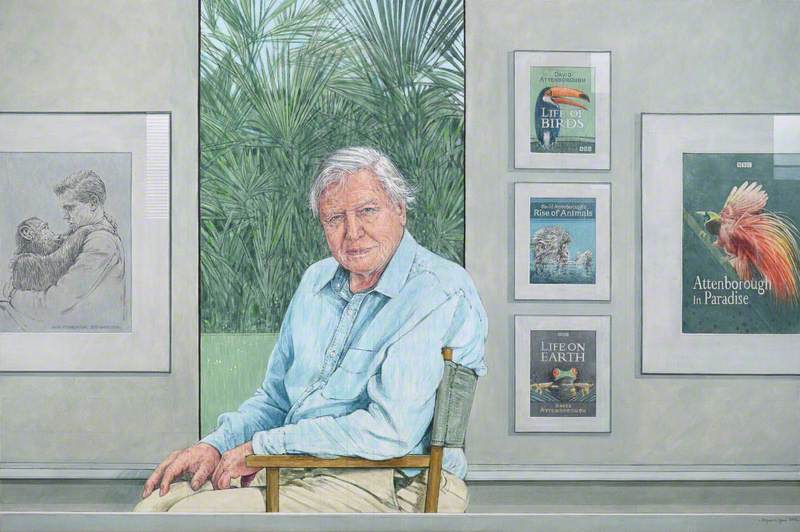

Moving from The National Gallery in London to the National Galleries of Scotland, we see another triumph in animal paintings in Edwin Landseer's The Monarch of the Glen. Landseer was one of Queen Victoria's favourite animal portraitists, and this painting became particularly popular when it was used on prints and advertising in the nineteenth century. It became such an iconic image that it has continued to inspire company logos to this day.

'You can see that Landseer's Monarch of the Glen is not trying to endow the animal with a psychology that is true to the animal and the behaviour of the animal, like we saw with Stubbs, but he is actually humanising the stag to a point that it almost looks like a human in disguise,' says Giovanni.

We would be remiss in this age of the Tiger King if we didn't take a look at one of the most famous representations of a tiger in western art history. Henri Rousseau's Surprised! shows a tiger crouching on his front legs, almost hovering above the foliage pictured. The leaves and branches are shown whipping to the side as they are lashed by rain. In the background, two streaks of lightning are seen in the distance. The tiger's eyes appear afraid, which begs the question – is he poised to strike, as we might think of a tiger, or is he cowering in fear?

'These jungles are not made in the jungle – they're actually produced in a very modern way. He would go to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, the greenhouses, the zoo and the natural history museum, sketch his subjects from leaves to animals, and then put them all together,' says Giovanni. 'He had this beautiful layering of leaves that introduces an iteration of collage that would be very influential to Picasso.'

One need only think of Damien Hirst's shark sculpture or Louise Bourgeois' spiders to see that artists have continued to depict animals in their work to this day. They draw on the subject for a number of symbolic and aesthetic reasons that keep us connected to nature, and hopefully help encourage us to be better cohabitants on this planet alongside our animal friends.

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes