As 'Rubens & Women' opens at Dulwich Picture Gallery, Director Jennifer Scott recounts the genesis of this groundbreaking exhibition that challenges conventional thinking about the artist.

About 15 years ago, I was reading a book about Peter Paul Rubens while travelling on the London Underground. A man sitting next to me glanced over at the open page and let out a gasp of horror before moving to sit further away. With surprise, I realised that an image that I considered a masterpiece might be perceived by others as shocking.

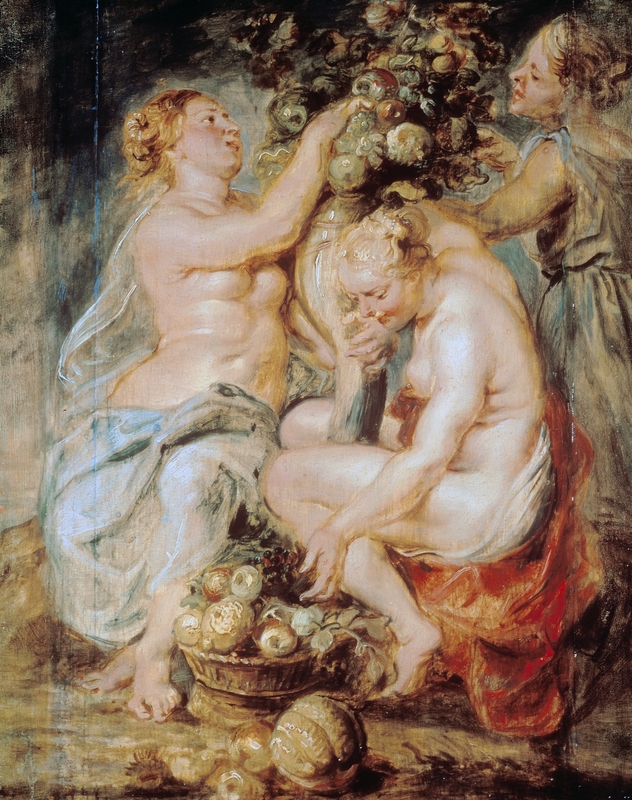

This experience has resurfaced over the following years. From social media censorship when posting Rubens' images, to grown adults giggling nervously at The Three Graces in Dulwich Picture Gallery, I have been reminded that Rubens is not easy. But he is also, in my opinion, one of the greatest artists of all time.

Rubens' earliest biographer, Gian Pietro Bellori, described him: 'He was tall, well-built, and of handsome colouring and constitution; he was dignified as well, and kindly, and noble in his manners and dress, being wont to wear a gold chain about his neck and to ride about the city like other knights and titled persons, and with this decorum Rubens upheld the very noble appellation of painter in Flanders.'

Clara Serena Rubens, the Artist's Daughter

c.1620–1603, oil on panel by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

Rubens was a family man and produced more portraits of his wives and children than almost any other artist, even Rembrandt. He was highly disciplined, well-read and able to multitask. Otto Sperling visited his studio in 1621 and recalled: 'While still painting he was hearing Tacitus read aloud to him and at the same time was dictating a letter. When we kept silent so as not to disturb him with our talk, he himself began to talk to us while still continuing to work, to listen to the reading and to dictate his letter, answering our questions and then displaying his astonishing power.'

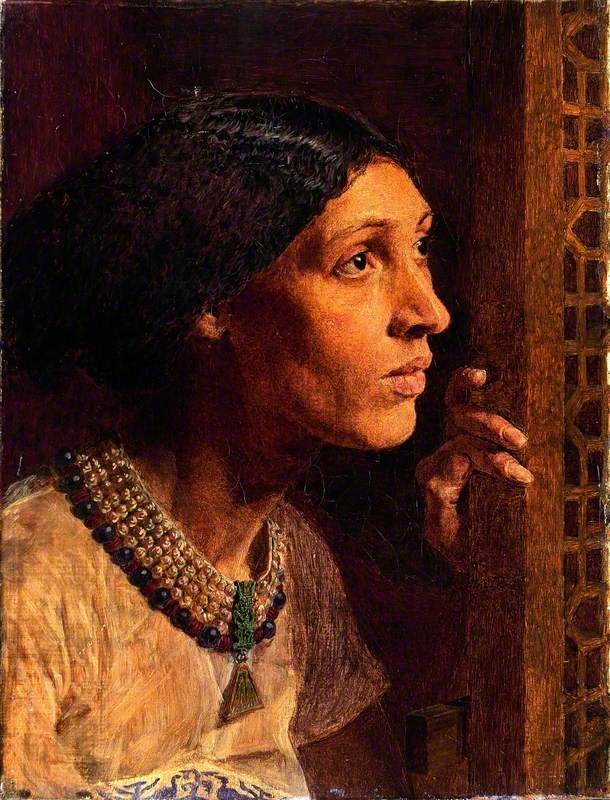

Isabel Clara Eugenia, Infanta of Spain, in the Habit of a Poor Clare

1625, oil on panel by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

In addition to these attributes, Rubens was also a diplomat, regularly travelling to England and Spain, representing Archduchess Isabel Clara Eugenia, Governor of the Netherlands, in her ongoing attempts to broker peace in the midst of European conflict. The Eighty Years' War lasted until eight years following Rubens's death in 1640 and he never knew peace in his homeland, aside from the Twelve Years' Truce of 1609–1621.

I became Director of Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2017. In keeping with my predecessors, I am determined to honour our founders' wishes to open up the significance of the Gallery's paintings for everyone. We care for, protect and champion one of the finest art collections in the world.

Early in my time at the Gallery, the team and I defined three different types of shows to give balance to our exhibition programme. These are: 'Revelatory' – shining a light on previously overlooked artists or art movements; 'Trailblazer' – celebrating leading artists or movements of their time; and 'Fresh Eyes on Great Names' – bringing new perspectives to the art of the past. 'Rubens & Women' is a 'Fresh Eyes' exhibition about an artist who has perhaps been misunderstood in recent times. Luckily, I knew exactly the curators to call upon to do justice to the subject.

Ben van Beneden and I first worked together when I was at the Royal Collection, London, and he was Director of the Rubenshuis in Antwerp. Ben is an excellent scholar with a long line of significant exhibitions to his name, including 'Rubens in Private' in Antwerp in 2015. Similarly, I first met Amy Orrock when I was curating 'Bruegel to Rubens: Masters of Flemish Painting' at The Queen's Gallery, Edinburgh, in 2007. Amy was completing her PhD at Edinburgh University and convened a study day for the exhibition. I knew that these two outstanding curators would create an insightful project. My only problem was they didn't know each other. I set up a meeting for the three of us in Dulwich Village in the spring of 2018, where they immediately clicked and started devising a show to explore the complexity and skill of Rubens.

As their starting point, they took this idea: Rubens was once described as a 'prince of painters and painter of princes', but this is somewhat misleading. In fact, many of Rubens's important patrons and subjects were women.

As we discussed this further it became clear that Rubens's relationship with his female sitters has been misconstrued in recent years. Perhaps as a result of the prevalence of nudity in his works, compounded by the fact that Rubens was successful, wealthy, intelligent and (overall) happy in his life, he does not necessarily strike a chord with current taste in the United Kingdom. In fact, much like the stranger's reaction to me looking at Rubens' paintings on the Northern Line, the artist can feel a little overpowering.

The Virgin in Adoration of the Child

c.1616, oil on panel by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

We decided the moment had come to set this right. Ben and Amy have carried out in-depth research into the circumstances surrounding Rubens's most famous paintings of women. The exhibition will pose key questions around beauty, faith, love and power. The women painted by Rubens – from his family members to the Archduchess Isabella, to Marie de' Medici of France to the Virgin Mary, to the Goddess Diana – radiate distinctive individuality through his artworks. What Ben and Amy uncover is that Rubens did not objectify women. Instead, he captured the sense of being in their presence.

In order to change his realistic painterly effects, Rubens looked to ancient Greece and Rome. He admired the way that classical sculptors evoked flesh and movement through marble, and he translated this into oil paint. Rubens' depictions of skin are so realistic, as though he breathes life into the portraits themselves. I'm thrilled that His Majesty The King has agreed to lend the ancient Roman sculpture of Crouching Venus to the exhibition so that we can see the inspiration that Rubens took from this celebrated sculpture.

Diana Returning from the Hunt

c.1623, oil on canvas by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and Frans Snyders (1579–1657)

Mounting an exhibition about Rubens is not straightforward, particularly because many of his paintings are fragile. For an ambitious artist, he showed one conservative strain: a continued preference for working on wooden panels. These were adapted as he went along, with strips added as the compositions developed. This renders many of his greatest works too delicate to leave the collections in which they reside today, most notably Het Pelsken from Vienna. Nevertheless, we have managed to secure 43 masterpieces, including loans from Dresden, Florence, Paris, Antwerp and from private collections that have never before been seen in the UK.

My favourite is The Birth of the Milky Way (1636–1638) from the Museo del Prado, Madrid. It will be directly compared for the first time ever with Venus, Mars and Cupid (c.1635) from the Dulwich collection. These monumental paintings unflinchingly celebrate the strength of motherhood. Venus nourishes Cupid; Juno uses her breast milk to create the stars in the night sky. Both convey Rubens's awe at the possibilities of the human body. His work is essential and beautiful and deserves to be enjoyed. If we are afraid of Rubens, then we are afraid of life itself.

Jennifer Scott, Director of Dulwich Picture Gallery

'Rubens & Women' is at Dulwich Picture Gallery from 27th September 2023 to 28 January 2024

This article was originally published in In View, Dulwich Picture Gallery's members' magazine